This year, the government will announce its autumn budget on 26 November. That later-than-usual date has many of our charity partners on tenterhooks, as they rush to finalise their 2026 budgets on time.

Ahead of the budget, journalists will fill many column inches speculating what the chancellor may or may not do, should or shouldn’t do. Instead of speculating, here’s what the government’s finances actually look like, and a helpful rule of thumb.

The government’s budget, in numbers

In the tax year 2024-25, the UK’s gross domestic product (GDP) was just under £2.9tn, and the government’s debt stood at just over £2.9tn, ie a debt-to-GDP ratio of 101%.

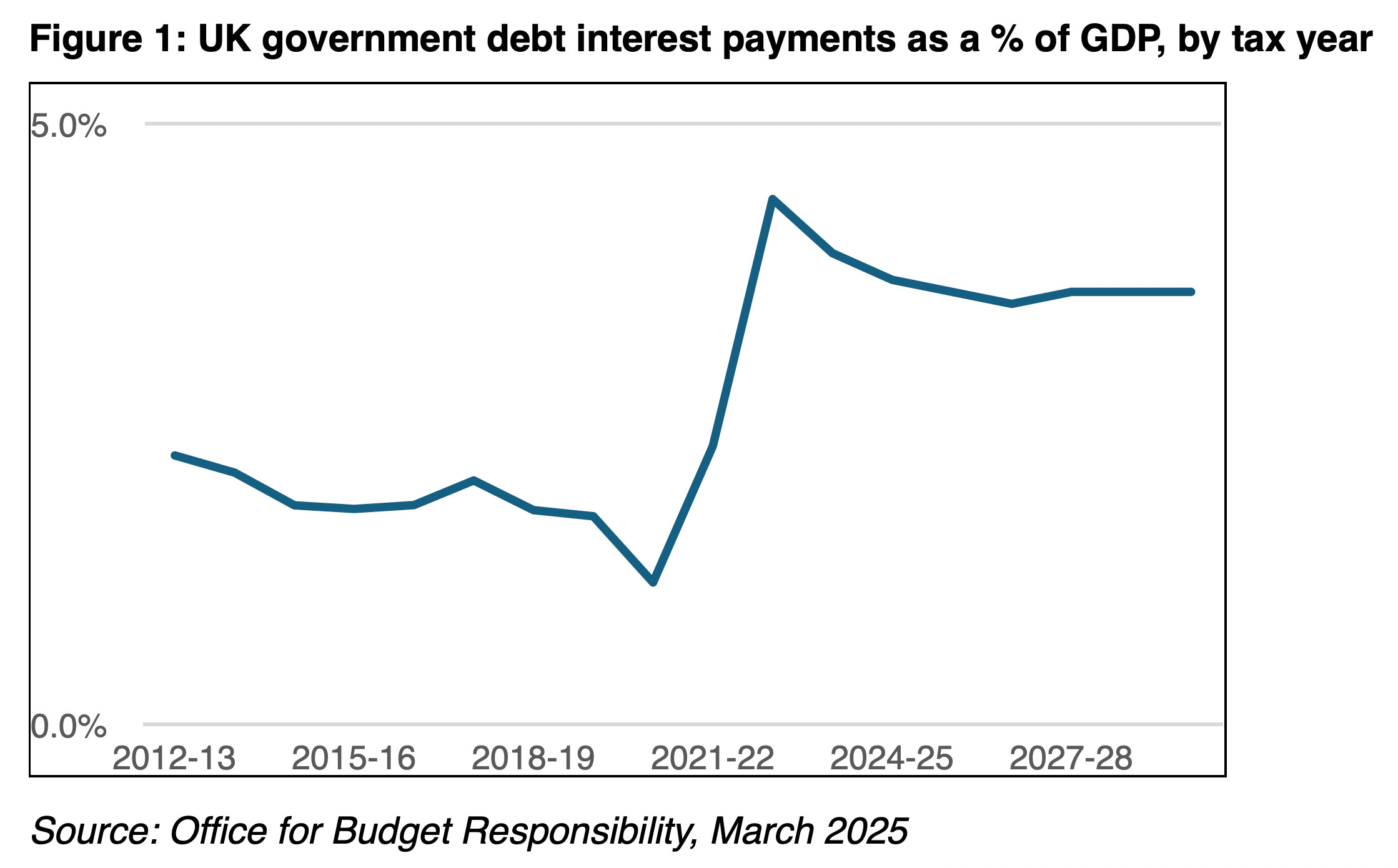

Annual interest payments on that debt have risen from £25bn in 2020-21 (1.2% of GDP) to £55bn in 2021-22 (2.3% of GDP) and £105bn in 2024-25 (3.7% of GDP).

For comparison: in 2024-25, the Home Office spent £21bn in day-to-day expenses, the Ministry of Defence £38bn and the Department for Education £89bn. Only health and social care spent more, at £190bn. By the numbers, therefore, you could consider interest payments to be the government’s second-largest department.

And those interest payments are over four times higher now than five years ago. That increase alone is nearly the entire education department’s budget, or more than twice the defence budget.

So, how much farther will these interest payments rise? And how sustainable is the UK government’s debt?

First, the good news: the increase in interest payments from 2020 to 2024 was exceptional, and it hasn’t continued. It occurred because interest rates, after a decade of ultra-low levels, returned to their long-term average in 2022.

In addition, a quarter of the UK government’s debt is inflation-linked, and inflation jumped in 2021-22. Finally, during the Covid-19 pandemic, the UK government took on more debt than usual to support the economy.

More good news: most major economists expect neither interest rates nor inflation to rise again soon. In fact, the Bank of England (BoE) has cut its official bank rate from 5.25% in mid-2024 to 4% in August 2025.

And inflation has fallen from 11.1% in October 2022, year on year, to 3.8% in August this year. The BoE, optimistically perhaps, expects Consumer Prices Index inflation to return to its 2% target in 2026. Barring unforeseen shocks, the government’s interest payments are expected to settle at around 3.6% of GDP for the foreseeable future.

How sustainable is the government’s debt?

The answer to our second question is more complicated: how sustainable is the current, higher level of interest that the government pays on its debt? A useful rule of thumb compares the average interest rate on government debt (let’s call that number “r”) with nominal GDP growth, ie real GDP growth plus inflation, which we’ll call “g”.

If r is larger than g, the interest rate on the government’s debt is larger than the growth rate of the economy. All else equal, this means that interest payments increase as a proportion of government spending.

In this situation, the government would need to increase its surplus in other areas to balance its books; in other words, save on things such as defence or education, or in other departments. That’s not sustainable in the long run.

If r is smaller than g, however, the interest rate on the government’s debt is smaller than the growth rate of the economy. All else equal, interest payments, as a proportion of government spending, decrease in this situation, and that is sustainable.

The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) estimates that the average interest rate on UK government debt will be around 3.7% in 2025-26, and that long-term nominal GDP growth will be 3.6%, made up of 2% inflation plus 1.6% output growth.

That narrow gap, between growth at 3.6% and interest rates at 3.7%, is precarious. Rising interest rates or a slowing economy could easily throw the UK off its path to debt sustainability.

It is also why the chancellor aims to balance her “current” budget by 2029-30, with a safety margin. That is, she aims to not spend more, before interest payments, than the money that comes in.

According to the OBR, her current budget will swing from a deficit of 1.9% of GDP in 2024-25 (or just under £60bn) to a 1.0% surplus in 2029-30. That’s the so-called fiscal headroom you hear about, a safety margin in case of unforeseen events.

Why it matters

Interest rates and GDP aren’t abstract concepts that only matter in the City of London, but numbers that matter to all our budgets. If interest rates rise or economic growth disappoints, the government may be forced to raise taxes and/or make spending cuts.

Those changes affect us all – including the charities, churches and local authorities we serve.