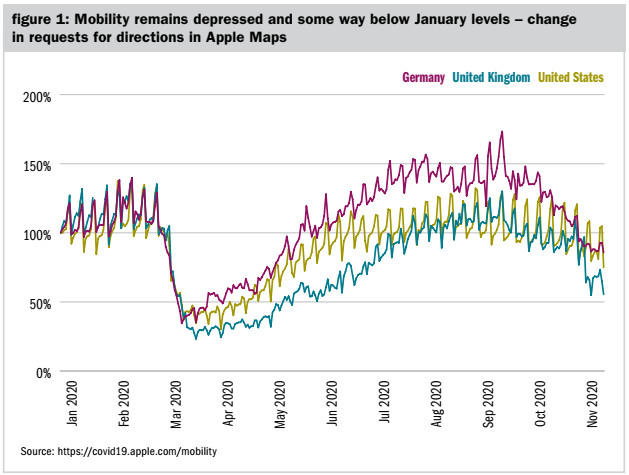

The use of letters to describe the trajectory of the recovery was very much in vogue earlier in 2020. Optimists talked of a V-shaped recovery while prophets of doom spoke of an L. Those in the W camp saw a more volatile path out of the crisis with some periods of optimism countered by setbacks as the spread of the virus picked up and restrictions were re-imposed. We preferred to rely on the letter K to capture the two separate and very different paths of the economy during the crisis. The upward line symbolising the parts of the economy benefitting from the pandemic – like many pharmaceutical and healthcare companies or the online consumer sector. The downward leg represented much broader group of companies suffering from the widespread lockdowns. Of these, energy companies, banks and utilities were among the worst hit.

The journey back to normality is uncertain. It remains to be seen how permanently scarred the economy will be and what Covid-era changes will become permanent. While positive news on vaccine trials and faster testing have been the cause of optimism around prospects for 2021, at the time of writing there remain some 2.5m people on furlough in the UK.

Debt glorious debt

While the path back towards a healthy economy will be challenging, we do see reasons to be cautiously optimistic – not least in the near term, as low interest rates can provide sufficient financial support to businesses, consumers as well as the public sector. Among the uncertain projections, one thing that we can be certain of is that we will be learning to live with a far more indebted economy. Government borrowing is forecast to rise to £350bn by the end of the year, which at 17% of GDP is a level never seen outside of the two world wars. In March, the government was forecasting borrowing of £55bn.

Although there was some much-needed cheer at the third-quarter GDP numbers, which showed a record 15.5% increase, this could not make up for the 20% contraction seen in the second quarter. The Bank of England is projecting another contraction in the last three months of the year followed by a sharp rebound in 2021. Many economists are less optimistic.

The heavy burden of government debt will necessitate a long period of low and even negative interest rates. The sharp move in interest rates in the wake of the financial crisis – from 5.25% at the start of 2008 to 0.5% in March 2009 – was seen as a temporary measure. However, in the past 11 years the interest rate has not risen above 0.75%. This new phenomenon has been bad for savers but good for asset owners. In this regard, it has heightened economic divisions in the country. It is hard to see a path out of this environment given that the government would struggle to service its debt if interest rates rose. Incredibly, investors have been happy to do their bit to help with government financing. At the start of October, the Treasury sold nearly £500m of index linked gilts with a maturity in 2056 at a rate of RPI-2%. Note that this was the yield at average accepted price – the auction price published by the DMO. Buyers of these inflation linked bonds were accepting a price below the anticipated inflation rate. Anyone looking to hold these bonds to maturity is accepting a return of around half of their investment after inflation in 40 years’ time.

Building back better

Boris Johnson and Joe Biden are among a number of leaders who have talked of wanting to “build back better” after the crisis is over. In the UK, the emphasis was put on accelerating infrastructure spending and housebuilding and promoting a green recovery. In March, the Chancellor announced record levels of spending on a series of infrastructure initiatives over the next five years. Further detail on the spending that we can expect has been delayed along with the autumn budget until next spring.

It seems likely that the government will honour its pledge to “get Britain building”. While interest rates remain at close to zero the previous focus on reducing the deficit through spending cuts has been replaced by the idea that we can grow ourselves out of our debt burden.

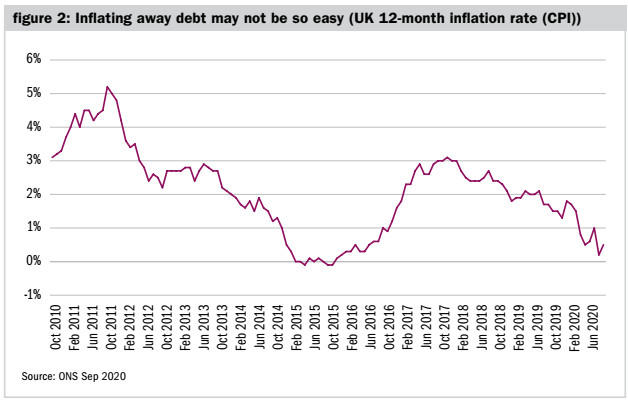

There is of course another way that the huge stock of debt could be brought down to a more sustainable level, and that is through inflation. This idea is certainly not official policy. Most central banks are mandated to pursue what they term a policy of price stability. The Bank of England has pledged to target an inflation level of 2%.

In Europe and in the US, however, there does seem more willingness to target a higher level of inflation. The European Central Bank announced in September that it would consider allowing inflation to overshoot target levels, focusing instead on the average level. The Federal Reserve has already committed to a similar approach. Changing the target is one thing, actually hitting it is another. There are a number of reasons to be sceptical about the ability of countries to inflate their excessive borrowing away. For a start, there are not many monetary policy levers left to pull. With interest rates anchored at or close to zero, central banks are left with asset purchases or QE and a means of managing future expectations of interest rate policy through what is called forward guidance.

Another cause for scepticism is the fact that inflation levels in the recent past remained low even as unemployment was falling to levels not seen for at least 40 years. Traditionally periods of low unemployment were associated with increases in wage demands and then inflation.

A greener future

The next UN Climate Change Conference (COP 26), which has been delayed until November 2021, provides an opportunity for the UK government to burnish its green credentials.

The environmentalist, Zac Goldsmith, who now has the wide-ranging title of minister for Pacific and the environment, has indicated that the government’s green agenda will become clearer as we head closer to the November conference. Examples of some of the projects that will form part of this agenda have started to appear. Before the end of the year the government is expected to announce some £200m in funding to support the building of 16 mini-nuclear reactors. The government says that enhancing the country’s nuclear power capability is crucial to support the pledge to meet its target of achieving net zero emissions by 2050.

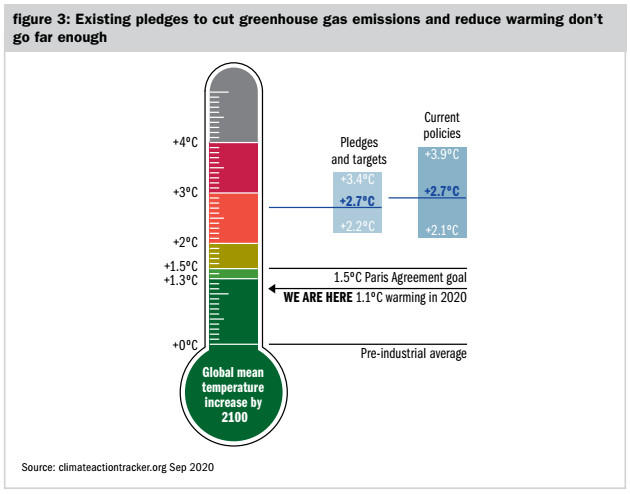

Despite recent pledges to reduce emissions global warming is still projected to rise above the Paris Agreement goal (see figure 3).

The move towards building a greener economy is undoubtedly gaining momentum. In September, President Xi Jinping made a somewhat unexpected but welcome pledge that China would become carbon neutral by 2060. As China is by far the biggest emitter of greenhouse gases this pledge had huge significance. In the following weeks Japan and South Korea also pledged to target carbon neutrality – in their case by 2050. Joe Biden’s victory in the US Presidential election suggests that the world’s second biggest carbon emitter will seek to set its own 2050 carbon neutrality goal as pledged in his manifesto. Since the launch of the Paris Climate Accord in 2015 some 75 countries have committed to achieve net zero CO2 emissions by 2050. It is to be hoped that the COP 26 event in November will provide the opportunity for yet more countries to demonstrate their commitment to supporting this pledge.

The reckoning

At some point we have to expect tax rises to help deal with the record levels of debt accumulated by government. However, the Chancellor is in a tight spot both politically and economically. The political challenge stems from a pledge by the Conservative party not to raise income tax, national insurance or VAT for the lifetime of the parliament. The Chancellor also recognises that he cannot raise taxes too quickly for fear of choking off the economic recovery. On this basis it would seem likely that significant tax increases will be left to the autumn budget next year.

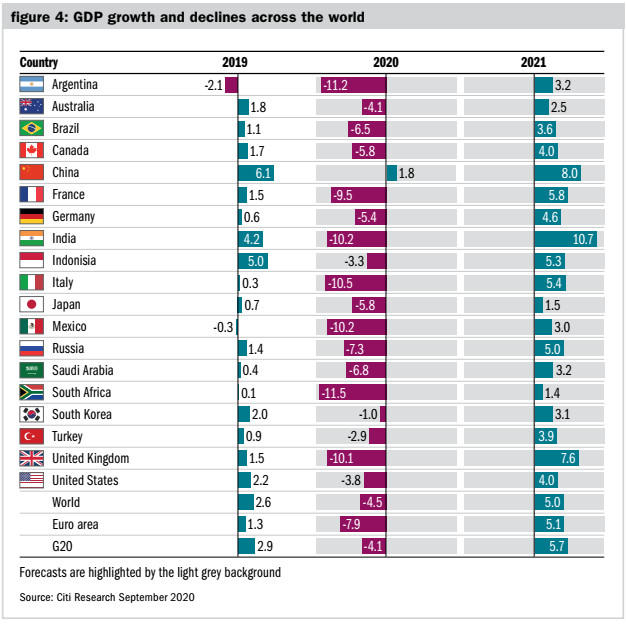

The UK is of course not alone in starting 2021 with a smaller economy than at the start of 2020. As figure 4 shows, the only major country not to see a contraction was China, which is expected to post modest growth of 1.8%. China has certainly dealt with the virus much more successfully than its counterparts in the West. It is attracting increasing attention from international investors into its equity market and also its bond market, which is now the second largest in the world.

The Communist Party recently unveiled its next five-year plan, which seeks high levels of economic growth.

Although only limited details have so far been made available, there seems little doubt that the country will seek to enhance its technology and innovation capabilities. The ongoing trade dispute with the United States and increased tension with European nations have perhaps accelerated plans to become more self-sufficient in areas where it has traditionally relied on foreign imports. At the same time the Chinese president has indicated a desire to open the country up further to inward investment while continuing to promote the belt and road initiative. As we look beyond the pandemic, China will continue to pose a dilemma for investors who are attracted by its growth prospects but at the same time wary of the political risks of investment.

The future, as ever, is uncertain, but on the whole it is looking increasingly more positive.

Patrick Trueman is a portfolio manager at James Hambro & Partners

Charity Finance wishes to thank James Hambro for its support with this article