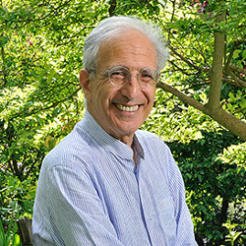

Michael Norton, winner of the Outstanding Achievement Award at The Charity Awards 2014

The Charity Awards judges selected Michael Norton to receive the Outstanding Achievement Award in 2014. Tania Mason met the man whose fingerprints are all over civil society.

If you’ve spent any time at all in the voluntary sector over the last 40-odd years, chances are you’ve come across Michael Norton – or at least his work. Even those that don’t know Michael, or are not familiar with his name, are likely to have trodden a path that he has helped to carve. His fingerprints are everywhere; in fundraising training, in youth empowerment, in women’s rights, in social franchising, in crowdfunding, in social enterprise – the list goes on. The deeper you delve into his expansive career, the more you realise just how ubiquitous and influential Norton has been.

Many will know him as the founder and first director of the Directory of Social Change; others as the driving force behind UnLtd, the foundation for social entrepreneurs that won a £100m endowment from the Millennium Commission. Others still will align him with Changemakers, or YouthBank; many more will have read one of his numerous books on fundraising or social change - 365 Ways to Change the World or The Complete Fundraising Handbook, perhaps.

It’s a journey that started after university, Norton recalls, when his father asked him if he was going to volunteer. “I almost didn’t even know what he was talking about, so illiterate was I about social action and social change,” he confesses. “But for an easy life I said ‘why not’.”

This took him to the local Jewish youth centre where he set up an old people’s visiting programme. One evening, he says, two 14-year-old girls came to the centre full of smiles because they had taken an old lady out for a walk – the first time she had left her flat in three years. “They said ‘we borrowed a wheelbarrow, put some cushions in it, carried her down the stairs and took her for a walk to the shops’. I was really impressed by that, by the fact you could just do something to make such a difference to people’s lives. All these health and social care workers couldn’t think to do that, yet these two young girls just had the idea and did it.” That firmly planted the seed in his mind that it was entirely possible just to do your own thing and put ideas into action.

A couple of years later, in 1966, this seed germinated and flourished into his first venture. He’d been thinking a lot about doing something around immigration and tackling racism, and then someone said to him ‘you can’t just go around doing good, you have to have a skill to do good with’. So he decided to use his English language skills to set up the UK’s first language-teaching programme for immigrant children and their families.

“In those days there was no child or data protection, so I would go to schools and ask for a list of families who have just arrived and don’t speak English. And then I would go to groups of young adults, mostly in their 20s, and say ‘would you like to volunteer, I’ve got something really interesting to do’ and I would send them along to give an English lesson. They didn’t know anything about teaching or education, they just did it. It was entirely voluntary – we had no name, no organisational structure, no bank account, no money - just a card index.

“It worked really well. In two years I had 250 volunteers, from accomplished actresses to out-of-work students.

“And actually, like a lot of projects, what you do is not always what you think you are doing – looking back what we were really doing was providing a bridge of friendship rather than English, because they would have absorbed English anyway.”