Preserving capital remains our guiding priority, and never has it felt more relevant. As we look ahead, we are informed by our observations of market patterns and investor behaviours over the past 25 years.

The equity bear market of 2001-2003 had its origins in the dotcom boom, and a quarter of a century on, markets appear once again to be suspended between promise and speculation. At that time, as is the case today, there was a bias to invest based on size rather than value.

While this has worked well in recent years, as the growth in passive investment bears witness, the market and macroeconomic environment is shifting in ways that challenge the assumptions investors have been able to rely upon for decades.

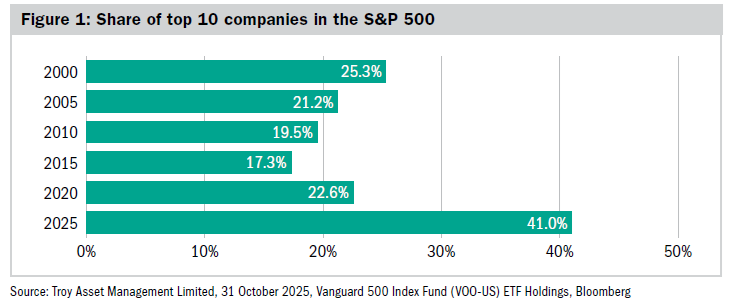

Equity markets have become dominated by a narrow group of companies. In the US, the top 10 names now represent more than 40% of the S&P 500 (figure 1).

This level of concentration is higher than at any point in well over a century, eclipsing the >25% peak in the year 2000, and even the c38% reached in 1900 at the height of the railroad era.

Passive portfolios that appear diversified may, in reality, be highly exposed to a single theme. AI is undoubtedly seeing exponential growth and extraordinary levels of capex, but it is possible to believe two conflicting things at the same time; AI may be the future in the way the internet was 25 years ago, but markets may still be over-extrapolating growth in the short term.

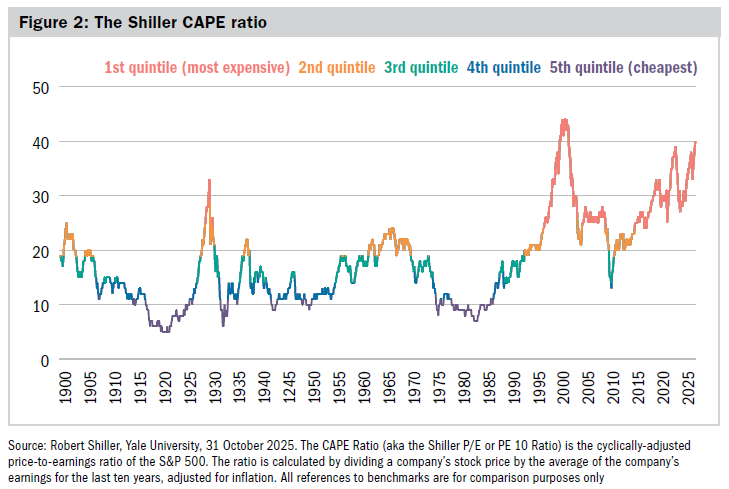

Market-wide valuations today are testing historic boundaries. The Shiller cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings (CAPE) ratio hovers near 40x, the highest level since November 2000.

With data back to 1871 – over 1,800 monthly observations – only 24 months have seen higher readings; from December 1998 to November 2000. As we consider the next phase, it is reasonable to question how sustainable these valuations and imbalances are, and how portfolios will behave when leadership changes.

Investor behaviour is also worth noting. Retail trading activity has picked up once again, with a renewed appetite for high-volatility strategies, with increased turnover and leverage also apparent.

Meanwhile, traditionally more defensive sectors, many of which contain high-quality, large-cap companies, have not looked more friendless since 2000 and we see an increasing number of opportunities in the types of companies we favour. Somewhat paradoxically, our equity allocation has risen this year as these valuation divergences have emerged.

The macro picture undoubtedly looks more fragile. Long-dated bond yields have moved higher across developed markets, with UK 30-year gilt yields reaching levels last seen in the late 1990s. Inflation remains elevated and monetary policy is no longer operating with full independence, with political priorities and fiscal constraints increasingly shaping central bank behaviour in some economies.

These behaviours, and central bank buying, have led to gold continuing its bull market into 2025, rising c50% in US dollar terms and c40% in sterling. We accept that there are some short-term risks to the price after such a strong run.

However, with central banks continuing to accumulate, and structural risks around debt and currency stability, and with geopolitical tensions, gold remains a rare store of value in a world of rising uncertainty. We therefore continue to see gold as a core holding going forward.

In summary, we see familiar but different patterns in the market’s current enthusiasm and concentration. The challenge is to resist the temptation of what glitters, to be dynamic when it matters, and to hold fast to what endures.

Charity Finance wishes to thank Troy Asset Management for its support with this article

Related articles