When Mark Carney became the first non-British governor of the Bank of England in 2013, few predicted the turbulence he would have to oversee.

His final few months in the job will not prove any easier. Nor will the task facing his successor when he hands over the reins on 31 January 2020.

Brexit remains very much unresolved. Economic uncertainty abounds, not only with regards to the outcome of Boris Johnson’s negotiations but also with respect to Donald Trump’s ongoing trade “war” with China. Emerging markets have become collateral damage in the tariff war. Eurozone growth is anaemic, weighed down by the woes of the German manufacturing sector. Tensions have flared up in the Middle East in response to the crippling of half of Saudi Arabia’s oil-producing capacity.

It is perhaps no surprise then that the Bank of England persists with its policy of low interest rates and bond purchases (quantitative easing) in an attempt to keep borrowing costs low and stimulate economic activity. Yet the decision is not as simple as it might first appear.

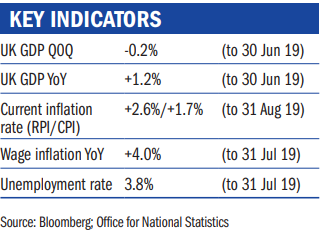

Historically, low unemployment has led to higher wages and increased inflation. Despite the current uncertainty, unemployment in the UK is at its lowest level since 1974 and earnings are rising at a healthy rate. Inflation is already creeping above the bank’s target of 2 per cent. The fundamentals point to rate hikes under any normal circumstances.

What’s more, any Brexit outcome may only add to the inflationary impulse. A positive Brexit outcome should improve sentiment, release investment and stimulate growth, which usually boosts inflation. On the other hand, a no-deal Brexit would likely lead to a further fall in the pound. With a net importing nation, this also has an inflationary impact, as a weaker pound means more expensive imports. This could cause uncomfortably high inflation just as economic uncertainty suggests cutting rates, leaving the bank in a bind. At the time of the referendum, inflation was running at 0.5 per cent, which gave significantly more room for manoeuvre.

The next governor will have to grapple with this dilemma. Raising rates in the face of Brexit uncertainty would be tough for the economy to stomach. But, with the fundamentals at a level that would precipitate rate hikes under normal circumstances, reacting too late could make any inflationary impulses much harder to control.

Ben Crawfurd-Porter is an investment associate at Ruffer

Related articles

|