We have witnessed extraordinary fiscal and monetary stimulus since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic and the unintended consequences of these measures remain uncertain. They could prove benign, but could also lead to persistently higher inflation; they could even spell the end of fiat currencies as we know them. However, I would caution that policy has not just been extraordinary for the last 18 months, but for the past 13-14 years.

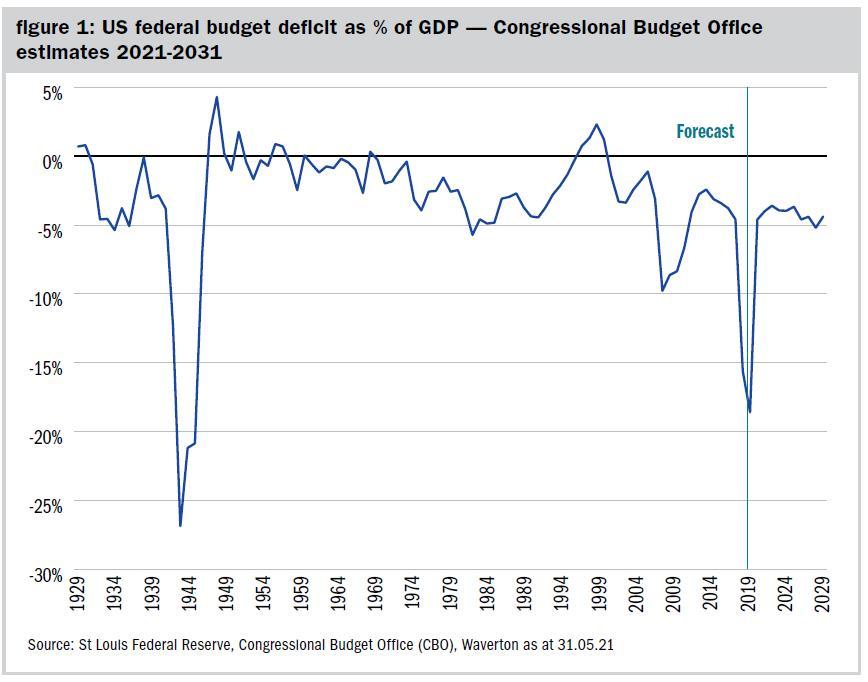

To provide some context as to the scale of stimulus that has been provided, the UK budget deficit reached 14% of GDP in March this year. This is the highest level since 1945 and has only been exceeded during WW1 and WW2 in recent history. The situation is even more extreme in the US, where the government’s deficit was 19% in March and remains at around 12% today.

This additional borrowing has enabled the implementation of remarkable policies. In the US, the welfare state has been expanded massively, with eligible families receiving $300 monthly cheques for each child under the age of six and $250 a child between six and 17 – this is child benefit on speed. In addition, 42 million Americans receive food stamps and these payments have been increased by 25%. Such initiatives mark a full reversal from the Reagan era, at which time the President claimed that the nine most terrifying words in the English language were: “I’m from the government and I’m here to help”. For the first time in 40 years, this is what most US citizens now want to hear.

Nevertheless, official forecasts generally indicate a return to lower deficits in the coming years. We will have to see what happens in this regard, but the Biden administration’s desire to spend an additional $1.75tn on top of the $6tn that has already been earmarked for Covid-19 relief makes us sceptical that deficit reduction will take place at the rate currently forecast, even if new taxes are implemented. Instead, we expect fiscal deficits to remain elevated.

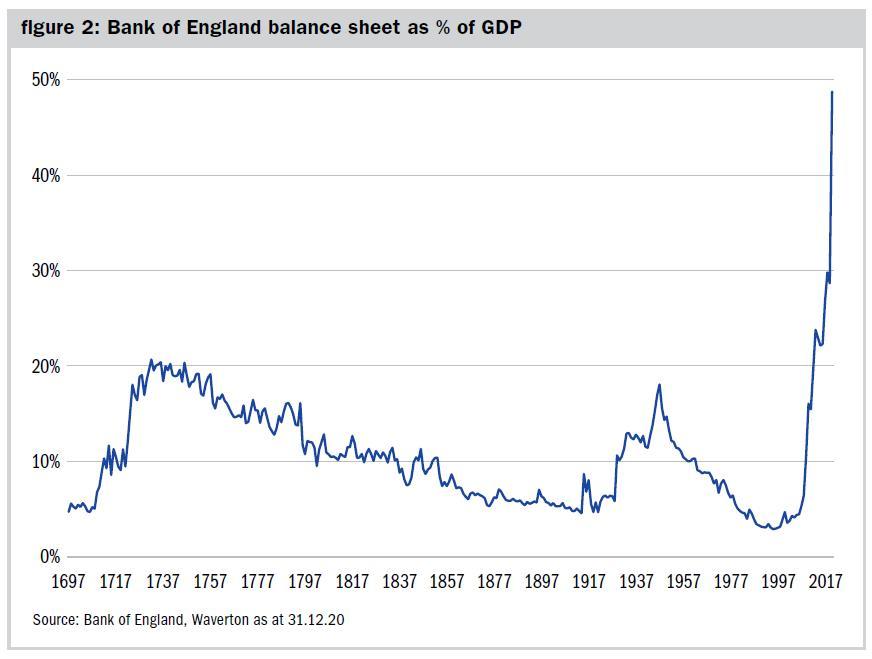

While government spending has accelerated to unprecedented peacetime levels, central banks on both sides of Atlantic have also taken QE to new heights. In the UK, the Bank of England’s balance sheet has reached around 50% of GDP, having not far exceeded 20% since its founding in 1694 (even during World War II – apparently, fighting Covid-19 is more difficult). This begs the question of what else central banks could do if there is a renewed economic downturn.

Given this policy uncertainty, it is perhaps unsurprising that policy decisions remain among the key drivers of markets at present. Currently, investors are focusing on asset purchase tapering by the Federal Reserve, with some fearing a repeat of 2013’s taper tantrum during which bond yields almost doubled and equity markets saw a significant wobble. Given that the US dollar is the global reserve currency and that the US Treasury yield therefore sets the global risk-free rate, the investment implications are potentially universal.

We are relatively unconcerned about this threat, given that the Fed is not currently having to buy all the government’s Treasury issuance as it was in 2013. Now, there are other sources of Treasury demand, which reflects greater market confidence. Nevertheless, the less central banks buy, the more the market has to absorb and this dynamic could push yields higher as tapering occurs in coming months.

For now, our base case is for a benign market outcome from tapering, with policy eventually helping to create a strong economy characterised by high corporate profits and low defaults.

Despite this, investors should expect negative real yields that will help reduce the debt mountain that has built up and for fiscal stimulus to continue to support those who have not benefited from monetary stimulus since the financial crisis.

The one key variable that could lead to a more disruptive outcome is inflation – a key risk to charities’ long-term reserves. Inflation is currently higher than it has been for the past decade, both in the UK and the US. And market expectations for inflation have been rising as can be seen from figure 4, which represent the market’s expectation for average inflation over the next five years. The UK inflation rate is for RPI but that equates to a CPI rate of around 3.5%, well above the Bank of England’s target.

At present, the market is giving policymakers’ the benefit of the doubt that the current bout of higher inflation will be transient in the US. If inflation were to average 3% over the next five years the Federal Reserve would be content as the central bank targets a 2% inflation rate over the cycle. Given that US CPI averaged 1.7% in the ten years from 2011 to 2020, a period of above 2% would be consistent with that target over the cycle. Nevertheless, the risk of a more persistent inflation cycle has certainly increased and investors should be looking to identify hedges that can protect their portfolios if price growth becomes less controlled.

We also note that persistently higher inflation could change the relationship between stocks and bonds. There has been a consistent negative correlation between the return you get from stocks and the return you get from bonds over the past 20+ years. But during periods of high inflation, equities and bonds can become positively correlated. That means bonds might not act as diversifiers for balanced portfolios if equities sell off. That challenge to portfolio construction could be one of the biggest consequences of a period of persistent inflation.

William Dinning is chief investment officer at Waverton

Charity Finance wishes to thank Waverton for its support with this article

Related articles