Generally, when we are thinking about the investment environment, we are focused on what is happening to fundamentals, valuations and technicals. Fundamentals include expected demand in the overall economy and for the products and services of an individual company. The valuation of assets tells us how much of our fundamental outlook is already in the price. We also need to consider investor sentiment and flows to determine the technical picture.

Policy is always an important part of the fundamental, and even the valuation, components. But this year policy has been “the” story. First, it was the policy in most of the world to restrict movement, close offices, schools and introduce social distancing in any place where people were still allowed to gather. This severely curtailed economic activity and justified the second policy of not just aggressive monetary policy but also aggressive fiscal policy aimed at mitigating the effects of lockdowns.

The result has been that in early 2020 we saw an equity market crash followed by a longer market rally. We will all have our views on where we go from here in the balance of 2020 and into 2021. But we have also been trying to step back and think about what some of the longer-term implications of what we have seen this year might be. I want to highlight two.

The first is whether the end game of policy response to lockdowns will be the creation of inflation. The second is whether the impact of the health crisis and the lockdown response to it has created an inter-generational schism which may impact public policy for years to come.

Will the end game be inflation?

We have learnt from recent decades that zero, or even negative, interest rates are not enough in and of themselves to generate a rise in inflation. Japan has experimented with extravagant monetary policy since 1994. The Swiss National Bank and the European Central Bank have set policy rates at negative levels in recent years. Two-year euro-area bond yields first went negative in 2012 at a time when there was still a vigorous academic debate about whether or not there was a “zero bound”. Today, gilt yields out to five years are negative, implying that the market is expecting the Bank of England to join the negative policy rate experiment.

Meanwhile, market expectations of future inflation have risen recently but remain at levels suggesting central banks will fail to hit their 2% inflation targets, let alone generate proper inflation.

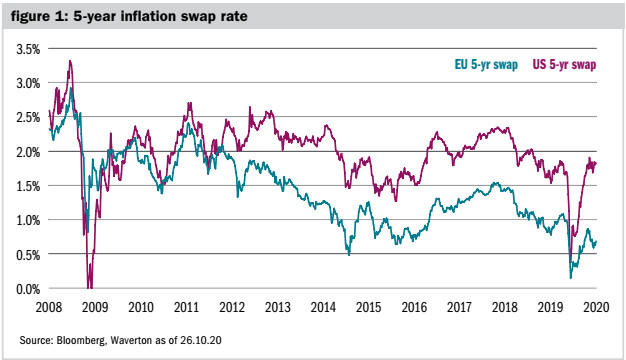

The chart below shows the five-year inflation swap rates for the US and euro area. This reflects the market’s prediction of future inflation and can be traded. If you are worried about inflation, you will buy a swap at the current price as the market does not believe that in either the US or euro area inflation will reach central bank targets in 2025. That seems pretty remarkable given that one of the differences between 2020 and the various policy experiments that have been underway since 2008 in particular is that fiscal policy has also been remarkably expansionary.

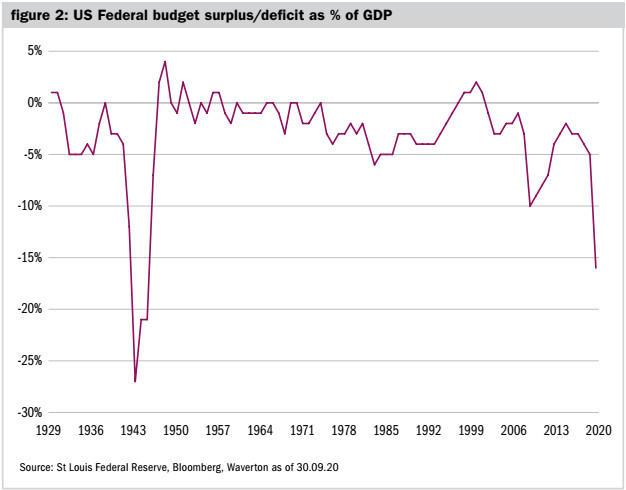

The chart below shows the US Federal Government budget deficit as a percentage of US GDP. At the end of September, it stood at 16% of GDP, the highest level since 1945. During the 2008/09 great recession, the budget deficit got to 10% of GDP in the US, and in the UK. The current level of the UK budget deficit will be similar to that of the US.

The combination of significant government spending and aggressive monetary policy has acted positively to cushion the impact of lockdown on many businesses and employees. But it also means that the economy in the US and here in the UK is even more dependent on low interest rates persisting. Any rise in interest rates would be very damaging to the ability of governments to finance their deficits, to the value of the assets on central bank balance sheets and to the corporate sector, which has also been able to issue record amounts of debt.

None of this guarantees an increase in the rate of inflation. But the possibility of higher inflation has risen in recent months, particularly in the US and UK where inflation has persisted, in contrast to Japan and the euro area where deflation has been evident on and off in recent years, or recent decades in the case of Japan. After all, inflation is one way to reduce debt burdens and that must make it an even more attractive policy to pursue today than it has been for many years.

If, as seems likely, we get a return to a more normal level of economic activity in coming years, and we persist with extremely low interest rates, the chances of economies overheating must be high. This is particularly the case given that the Federal Reserve has changed its policy on inflation to targeting the average level of inflation, not to targeting 2% at any point in time. So, the Fed is saying it will let the economy run hot for a while. It is interesting to us that the market is not pricing future inflation at higher levels given the above.

Inter-generational schism

Inflation represents a transfer of wealth from asset owners to debtors. Which means that higher inflation has attractions to policy makers as one way of grappling not just with their own debt burden but with the fact that the young are taking a very big hit economically in 2020.

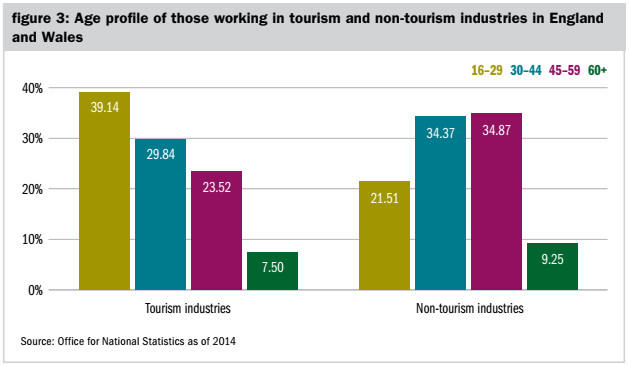

Here in the UK, the young have suffered from the policy response to the virus from both major disruptions for those who are in full-time education and significantly greater risk of unemployment for those in the workforce. The chart below shows the age profile of people working in tourism-related industries and non-tourism-related industries. By this definition (which includes hospitality, restaurants, performing arts), tourism-related industries are 11% of UK GDP.

Under 30s represent 39% of the workforce in tourism-related industries but only 22% of the workforce in the rest of the economy. The young are therefore much more likely to be unemployed or furloughed than any other cohort of the workforce.

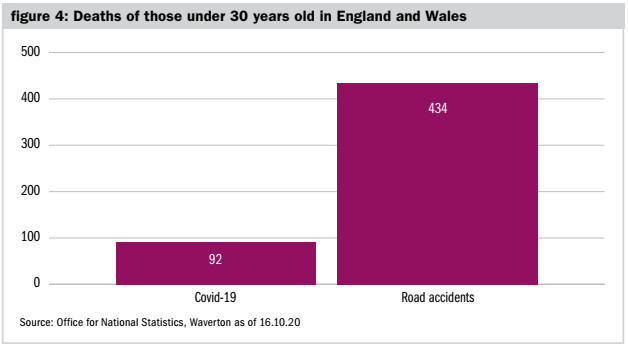

This is unfortunate. It is particularly unfortunate given that the reason for the distress being caused to the young is a virus that is much less dangerous to them than many other things, not least travelling in a motor car.

The chart below shows that up to 16 October, 92 people under the age of 30 have died from Covid-19 in England and Wales. In 2018, 434 people under the age of 30 died in road accidents.

So, if you are at school or university, or in the workforce, you have likely had a difficult time of it in 2020. You might say the young have often paid the price for their elders’ actions. Armies, after all, are not made up of many generals. But on this occasion, we do wonder if the events of 2020 will catalyse a different public policy approach to the young.

Let us take university students for example. They are currently charged £9,250 for a year’s worth of tuition. There are 1.3m students in England who between them borrow £17bn a year. The average debt among the cohort of borrowers is £40,000 after a three-year course.

This has always been a controversial policy, but in 2020 it is even more so given that few if any students are having a normal university experience. This is annoying to not just the students but also to their parents. Particularly if their parents were the beneficiaries of the old grant system whereby students received money to go to university. That was the case, for example, when I was at university. I received a full grant which amounted to £1,100 in 1979, or £6,400 in today’s money, after inflating by RPI. That gap between owing £9,250 and being paid £6,400 is a large one and is symbolic of how public policy has changed in recent decades.

One way to think of the old grant system is as a kind of universal basic income. It was only available to a proportion of the 7% of 18-year olds that went to university 40 years ago. But could we see policy shift to providing some direct support to the young? In the old days we would have to ask how that would be funded, and the answer would be taxation on those with wealth. That may not need to happen in the short term but ultimately it too may be required.

Napoleon famously said that if you want to know the man, ask what the world was like when he was 20. Napoleon was 20 in 1789. What of those who are 20 today? They could well carry into the rest of the lives the uncertainty and in some cases hardship they are encountering. There could be many forms of long Covid, not just lingering health effects but also lingering public policy effects too.

William Dinning is chief investment officer at Waverton Investment Management