The charity sector is no stranger to the reality that inequality has been growing, but is this, in isolation, the main driver behind the levels of political disruption we have experienced? Many people in the US, UK and Europe aren’t just seeing inequality, they are feeling poorer than they were; and the statistics back them up.

Recent years have seen some significant surprises in elections and referendums. The most notable are the majority of the UK electorate voting to leave the European Union (EU) and the election of Donald Trump as US president, both of which happened in 2016. But there are others, including the Italian election earlier this year which produced a coalition government between two anti-establishment parties.

Each of these electoral surprises has had impacts on financial markets. Some have been positive with President Trump’s tax cuts, for example, giving a boost to corporate profitability and to the stock market.

However, most of the surprises have had a negative tone to them. The UK’s ongoing negotiations with the EU, for example, have created considerable uncertainty. In Italy, the bond market has reacted negatively to the possibility of a showdown between the government and the European Commission over fiscal policy. In the US, President Trump’s use of tariffs on steel, aluminium and a lot of imports from China are a reversal of economic orthodoxy in place since World War Two.

In the US and UK in particular, electorates are bitterly divided. The US mid-term elections have confirmed that polarity with the Republican Party losing control of the House of Representatives but maintaining its majority in the Senate. The Democrats could well attempt to impeach president Trump, although the chance of his being convicted in the Senate is very small.

With politics this heated there can be a tendency to get tied up in the minutiae of policy. Take the negotiation between the UK and the EU for example. This has, at times, appeared to be the only news story in the country. This is not surprising given the importance of our future relationship with Europe.

However, it is somewhat surprising that there has not been more focus on the issues which have caused voters on both sides of the Atlantic to make the choices they have. In our view the disillusionment of the electorates are rooted in economic insecurity.

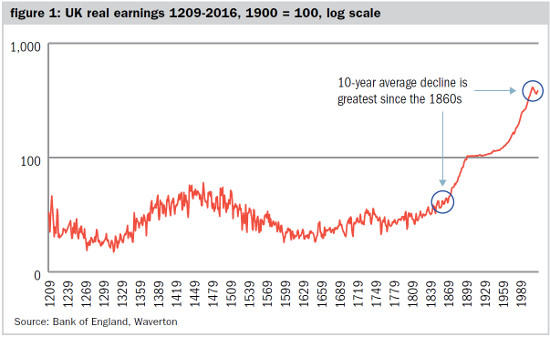

This is most starkly evident in the UK if we look at a series from the Bank of England measuring real wages, ie wages adjusted for inflation. Figure 1 starts in 1209 and shows that, until the industrial revolution of the 19th century, people had not seen a consistent improvement in their real earnings for 600 years. In the 19th and 20th centuries, real earnings increased significantly.

What is startling about the chart, though, is that in the period 2006-2016 real earnings fell. This is very unusual and the magnitude of the fall is also quite remarkable. The average annual decline over those ten years was the greatest since the 1860s.

It is widely recognised that people have been feeling more economically insecure even though, by some measures, the UK economy is doing well with its lowest unemployment rate since 1975 for example. However, the Bank of England data show that insecurity is grounded in reality. Given that, it is perhaps less surprising that people took the opportunity to protest and voted to leave the EU. And in Italy, the decision to give the anti-establishment parties a majority is also rooted in economic disappointment.

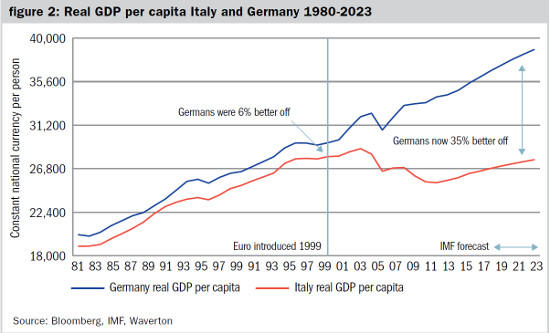

Figure 2 shows GDP per capita in Italy and Germany since 1980. At the time of the introduction of the Euro, German GDP per capita was 6 per cent higher than Italian. Today it is 35 per cent higher.

Italian disillusionment with the status quo appears well founded when looked at this way. We can debate whether the Italian government’s policy response of fiscal stimulus is the right one, but that something different is being tried is understandable.

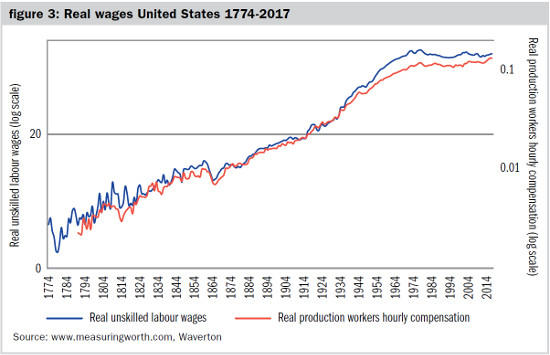

The disillusionment being felt in the US is also explicable. Figure 3 shows two different series illustrating the wages of unskilled labour (the blue line) and the hourly earnings of production workers (the orange line), both shown adjusted for inflation going back to 1774.

The former series peaked in 1978 meaning unskilled labour has had declining real income for 40 years.

The hourly earnings of production workers are increasing but not at the rate they used to. Over the last ten years the average real increase has been just 0.9 per cent. The last time the average increase was 2 per cent or greater was in 1972.

With economic dislocation like this in evidence around the developed world we think it quite probable that there will be more electoral shocks to established political parties. There is no easy solution to the problem of falling living standards so this will not go away quickly even if low unemployment rates in the US and UK in particular suggest we may get some wage inflation in coming years. Looking at these data points would suggest that some wage inflation would be no bad thing from the perspective of returning voters to the more conventional parties and politicians.

The prospect of further electoral surprises is something that we think investors should expect. Disillusionment with established political parties makes any election a possible surprise. Even in Germany, by any standards a successful economy, the established parties have done badly in regional elections and chancellor Merkel has already stated she will not run for national office again.

It is difficult to construct an asset allocation around these uncertainties, although some things spring to mind.

First, there are identifiable winners from some of the policies being pursued. For example, Vietnam is the second largest exporter of smartphones after China and it could be a beneficiary of information and communications technology companies looking to move away from China if tariffs persist. Other countries in South East Asia could also be beneficiaries of higher foreign investment.

Second, currency fluctuations could be higher than normal in the UK for example. Even if the Brexit situation is resolved, the prospect of the Labour Party being the beneficiary of the political turmoil in the UK will likely keep sterling volatility high.

Thirdly, it seems likely that tariffs will be used further by President Trump meaning there will be the possibility of further shifts in trade relationships which will need to be watched closely for any sign that they are negatively impacting global growth.

Finally, the Italian government is on a collision course with the European Commission over its fiscal policy. How this plays out will have implications for not just Italian bond yields but also potentially the market’s view on the Euro.

In short, political risk needs to be added to the traditional analysis of cyclical, valuation and technical indicators when constructing a portfolio.

William Dinning is head of investment strategy & communication at Waverton

Charity Finance wishes to thank Waverton for its support with this article