Balancing the needs of today with those of tomorrow

A goal that most charities share is to operate and spend sustainably, so that the real spending power of future trustees is equal to (or greater than) those of today. Traditionally, charities invest to provide an income that can be spent today while also growing capital and income in order to maintain their real (after inflation) spending power. This balance between supporting today’s grant giving and ensuring that future real spending power is maintained is a particular challenge in today’s economic environment.

Each charity will have its own unique set of circumstances, objectives and activities, making it difficult to provide a one-size-fits-all solution for how much a charity should spend from its investment portfolio. This article is designed to help trustees understand the challenges ahead and plan accordingly.

Setting a sustainable spending plan

A charity’s current rate of expenditure and reinvestment is one of the most direct ways it can affect its investment portfolio.

A charity can ultimately decide between the following:

1. Spend more today > less invested into portfolio > capital value shrinks > lower investment income in future years;

2. Spend less today > more invested into portfolio > capital value grows > greater investment income in future years.

While this is a very simplified model, it is helpful to understand the relationship between spending, reinvestment and future income. When considering the returns from an investment portfolio there are a number of factors that might influence the actual outcome.

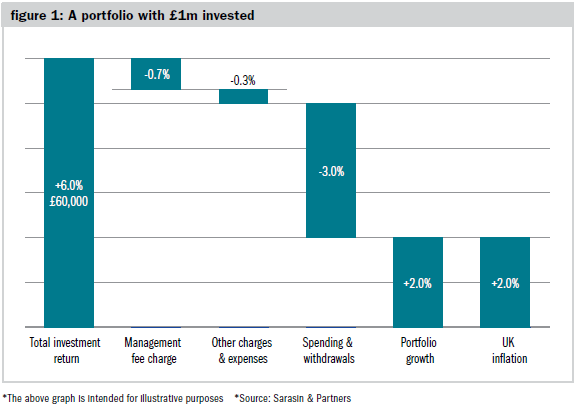

One can see from figure 1 that if a portfolio is projected to produce a total return of 6 per cent per annum and the trustees spend 3 per cent per annum, then the capital should grow in line with inflation (assuming inflation averages 2 per cent and with no margin for error) after total fees and expenses of 1 per cent.

What this chart demonstrates is that the growth in the portfolio’s value is not only driven by investment returns, but is also impacted by investment management charges, additional costs and withdrawals.

Given low bond yields and future economic growth expectations, what lies ahead?

Looking ahead, the challenge is that future returns from a traditional endowment portfolio are likely to be lower. This is a function of both the low interest rate environment, which has reduced the expected returns from all fixed interest asset classes, and lower expected economic growth, which, ultimately, drives corporate profits.

Asset markets have enjoyed a decade of strong returns and relative calm. Since the 2008 financial crisis, monetary policy has been very supportive, with low interest rates and quantitative easing seen across most developed economies. While this has helped fuel the longest-ever US stock market run, it has also caused a compression in bond yields, bringing them to historic lows. Today, a ten-year UK government bond offers a yield of just 0.5 per cent per annum.

We also expect returns from equity markets to be lower than in the past. This is ultimately due to long-run economic growth expectations being lower in the future, because of slowing population growth, ageing demographic, and lower productivity gains. So what does that mean for trustees looking to set sustainable spending policies?

When we model the returns a typical endowment portfolio might be able to generate, we estimate a total return of 6 per cent before costs. As figure 1 illustrates. this would suggest that a sustainable withdrawal of 3 per cent might be possible while retaining the real capital value of the portfolio.

This is lower than may have been historically achieved. In the Sarasin & Partners Compendium of Investment, we model how a typical endowment portfolio may have performed over time. The study shows that from 1900 to 2017, trustees could have spent 4 per cent a year after costs and still maintained the real capital value of the portfolio.

In the recent past, trustees could have spent more of their investment returns. Since 31 December 2008, the endowments model fund has generated an expendable return, after costs and inflation, of 5.6 per cent per annum.

While pockets of opportunity and growth still exist, there is heightened uncertainty and doubt around the future. As illustrated by the endowments model, recent years have been kind, but it would now be wise to proceed with a degree of caution to ensure sensible budgets are made.

If returns and therefore sustainable withdrawals from an investment portfolio are projected to be lower, what should trustees consider?

There is a delicate balance between protecting the real capital value of a portfolio and maintaining spending levels in a low-return environment. Below are five factors that investors may consider when considering this:

1. Managing risk and income bias

To try to achieve the same returns and income as in recent years, some investors may take on more risk, shift towards higher-yielding assets or apply leverage. We would advise caution.

As well as diversifying a portfolio’s asset allocation, investors should manage risk by diversifying sources of income. There are a range of income sources that span the risk spectrum – such as government bonds, corporate bonds, equities and alternatives. As well as balancing their allocation to these different assets, investors should have a degree of geographic, sector and style diversification. This helps reduce portfolio risk, so that a downturn in one particular market does not severely erode the portfolio’s overall return and income.

Some investors choose to have a heavy bias towards stocks that offer particularly high dividends. While this may generate higher income in the short run, it may neglect stocks that have a low yield but the potential for strong capital and income growth, which would ultimately reduce the portfolio’s future income.

2. Alternative sources of return and income

For investors seeking to diversify their sources of return and income, alternative investments can offer a solution. These can include non-traditional assets, such as commodities or infrastructure, while others invest in traditional assets through non-traditional channels, such as hedge funds.

One example of this is infrastructure funds, which have become increasingly popular with investors seeking new sources of income and growth. Some can be lower-risk public-private partnerships, with government-guaranteed and inflation-linked income streams. Investing in infrastructure typically provides three key benefits: an element of diversification; a consistent income stream; and a degree of inflation protection.

3. Total return investing

Charity trustees have increasingly adopted a total return approach to their spending. The Charity Commission allows even those with permanently endowed capital to consider total return withdrawal policies. This permits them to spend their portfolio’s capital growth (after inflation), as well as its income.

With interest rates and bond yields at record lows, embracing a total return approach to investing would make sense. It allows for a more diversified portfolio with less dependence on income assets and better overall performance, while also giving trustees more flexibility on how they meet their long-term spending requirements.

For example, rather than targeting an income yield of 4 per cent to fund their expenditure, trustees may instead opt for a yield of 3 per cent, while spending 1 per cent of capital per annum.

However, while we suggest charities operate a total return approach to withdrawals, we would not advocate being agnostic about income. We believe a sustainable income stream lies at the heart of a successful investment strategy.

4. Be clear about what is truly long-term money

For near-term obligations that may require money to be withdrawn, it would be appropriate to have a designated short-term portfolio. This should primarily be invested in safer, more liquid assets. Short-dated government bonds can generally be relied on to provide consistent returns that are marginally higher than the interest from cash.

Portfolios that are intended as truly long term (five years or more) investments should be able to withstand short-term volatility of capital and income, and this should be expected to a certain degree. By being clear on how much of a charity’s investments are long term and not required for withdrawals in the near term, trustees can enable their investment manager to maximise returns over the full time horizon, rather than being forced to sell at an inopportune moment and crystallising losses.

5. Costs and charges

While investment performance is critical to choosing an investment manager, trustees should also be aware of the associated costs and charges. As we illustrated earlier, these could have a material impact on the sustainable withdrawals a charity can make from its investment portfolio. Investment managers often quote a headline management fee, but there are often additional charges, such as operating expenses, custody costs, performance fees and thirdparty fund fees.

Trustees should feel empowered to request transparency and clarity on costs and charges, as this has a material impact on their investment returns and income.

The key to achieving sustainable spending is to review regularly

In the Compendium of Investment we have illustrated what could have been withdrawn from the endowments model, while maintaining its real value. The study found that in the 1920s, 1950s, 1980s and 2010s, there was an expendable return of about 8.6 per cent per annum (after inflation and costs). Meanwhile, in the 1910s, 1970s and 2000s, returns barely kept up with inflation, which meant that spending any part of the return would have resulted in a reduction of the real value of the assets. This draws out a pattern of distinct feasts and famine.

Unfortunately, the compendium and other studies have found that there is no formulaic spending plan that guarantees success, assures long-term growth in expenditure or can avoid too significant a withdrawal during downturns.

This is the case whether one withdraws:

- Just the natural income generated by the portfolio;

- An initial sum that is increased by inflation each year;

- A fixed percentage of the yearly capital value of the portfolio;

- A fixed percentage of the three – or five-year rolling average capital value of the portfolio;

- Any combination of the above.

We would recommend that trustees adopt a spending plan that is in keeping with the returns they expect their portfolio to generate over the medium to longer term. The past decade has been very generous to investors, but we would guard against extrapolating past returns into the future – going forward, we expect returns to be lower.

With this in mind, it would be wise not to apply any given plan too rigidly but instead to regularly review the impact of withdrawals, fees, inflation and market returns on a charity’s investment portfolio.

James Hutton is a partner and Kamran Miah an investment manager at Sarasin & Partners

Charity Finance wishes to thank Sarasin & Partners for its support with this article