What you should own and when you should buy it are two of the most difficult yet crucial questions in investing. One useful framework for thinking about them is the investment clock. Traditionally, these clocks mapped the economic cycle, to guide investors to the asset classes most likely to perform in each phase. But, if – as we believe – the world has entered a period of higher and more volatile inflation, perhaps a new investment clock can help investors prepare for the coming inflationary waves.

We have long argued that the world is entering a different investment regime characterised by higher and more volatile inflation, and that 2022 marked the start of this new era. We see several waves rolling in which will put upward pressure on prices, and risk severe market and political upheaval. The re-election of President Trump has both exemplified and exacerbated many of these waves.

First, geopolitics. The world order is changing, as Russia in Ukraine, Iran in the Middle East and China in the South China Sea all seek to challenge US dominance. This has brought home the need for greater defence spending and more robust supply chains, both of which raise prices. Wars – whether hot or cold – are always inflationary.

Second, debt dynamics and big government. Fiscal deficits in the West are swollen, and interest rates have risen. In 2024, the US government spent more on servicing its debt than on defence. How long can that be sustained? Yet the new administration was voted in on a platform of tax cuts (which will worsen the US deficit position unless it can make commensurate efficiencies), and more spending seems to be favoured by governments on both sides of the Atlantic.

Third, migration and demography. In many countries, including the West and China, populations are ageing, leaving fewer working people to support the old and shoulder the fiscal debt burden. By contrast, there is huge population growth in the developing world. Climate change is having a drastic impact on these regions, and mass migration to more temperate zones could cause greater upheaval.

Fourth, the energy transition. Reducing our consumption of fossil fuels without lowering GDP growth and living standards won’t be a smooth journey. And it certainly won’t be cheap, adding to price pressures.

Last, technology. Whether or not AI drives a productivity boom, it is guaranteed to be disruptive. And research shows that new technologies are often initially inflationary, as the benefits flow to a few superstar firms.

We could be wrong. But we believe it’s more likely that inflation is back, and markets will have to cope with it both being more volatile and having a floor of 2%.

Delayed action

If the inflation surge and accompanying market falls of 2022 did indeed move us decisively into a new world, the impact of that shift has arguably yet to be truly felt. Markets recovered in 2023, and equities made new record highs in 2024. So what does this all mean for investors’ portfolios?

The experience of 2022 revealed that most assets used to provide diversification to equities were in fact hugely sensitive to rising interest rates. And some, notably private equity and debt, were also illiquid. As conventional assets fell in tandem, many investors discovered they had no uncorrelated sources of return: everything fell together.

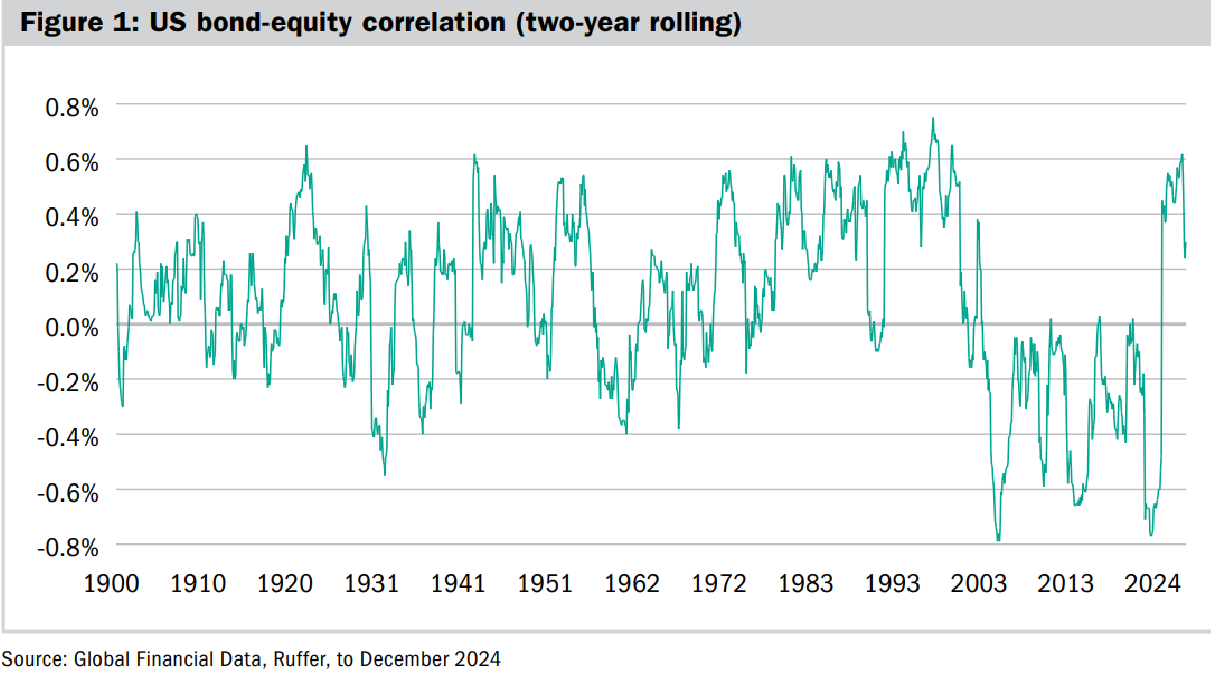

Was this just a blip? Will everything return to normal? Possibly. But, if we look back over 100 years, we can see that positive correlations between the major asset classes are what’s actually normal (figure 1). Rather, it is the experience of the last three decades which looks very much the outlier – a period without inflation risk.

So, if we have in fact entered a new era of higher and more volatile inflation, existing approaches to portfolio construction may no longer provide adequate diversification. But how do investors know what to own? And when to buy?

There are many frameworks for considering these challenges, and one we think can be useful is the investment clock.

Time is our friend

The first mechanical clocks, built in the late 13th century, didn’t have faces. They simply tolled a bell to mark the hours for the local community. Then some bright spark had an epiphany: the existing mechanism could be used to show the passing of time between the hours, originally by a fixed hand pointing to a rotating dial with the hours on.

Push the dial on to the late 20th century, and the clock face was adapted for a new purpose. The concept of investment clocks grew out of macroeconomic and investment cycle theories popularised by strategic asset allocators in the 1980s and 1990s. Like their time-keeping counterparts, investment clocks came in a range of shapes and configurations. Their common purpose: to provide visual aids for managing portfolios through the phases of the economic cycle.

Well-known investment clocks

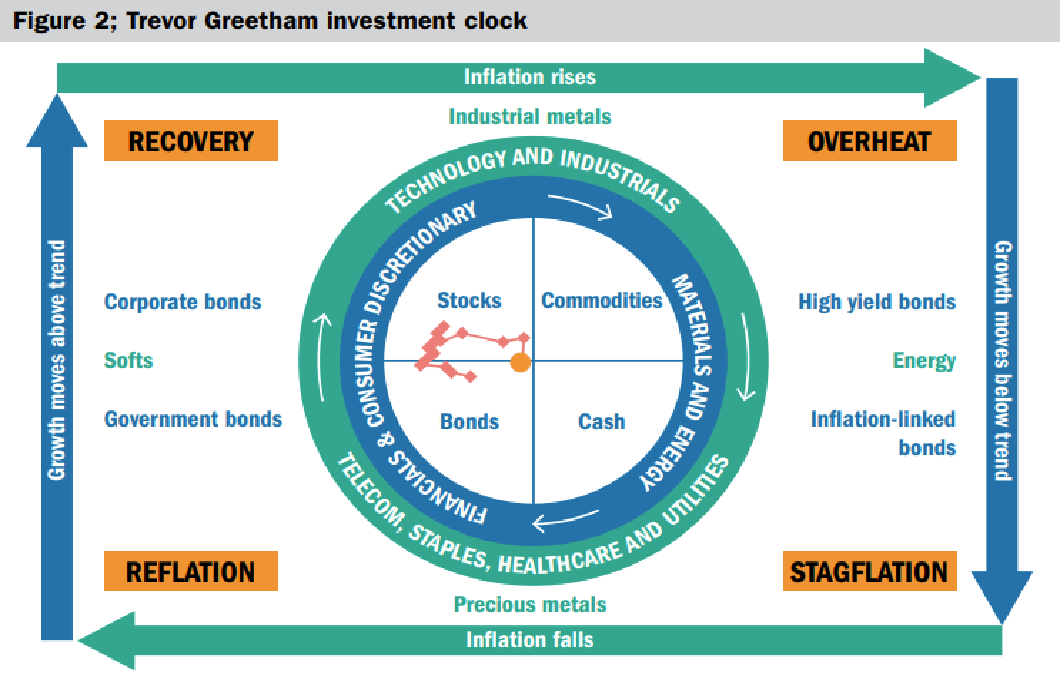

Perhaps the best-known example of an investment clock was produced by Trevor Greetham at Royal London (figure 2). The output of 20 years of research, it aims to be a framework for understanding where the economy is heading in terms of growth and inflation and then relating that to the performance of different asset classes.

While this captures the direction of inflation within the economic cycle, it doesn’t account for the level. Doesn’t experience tell us that different asset classes will perform if inflation is rising from a low base than if it is rising from an already high level? It’s time the investment clock had a facelift.

Teun Draaisma chimes in

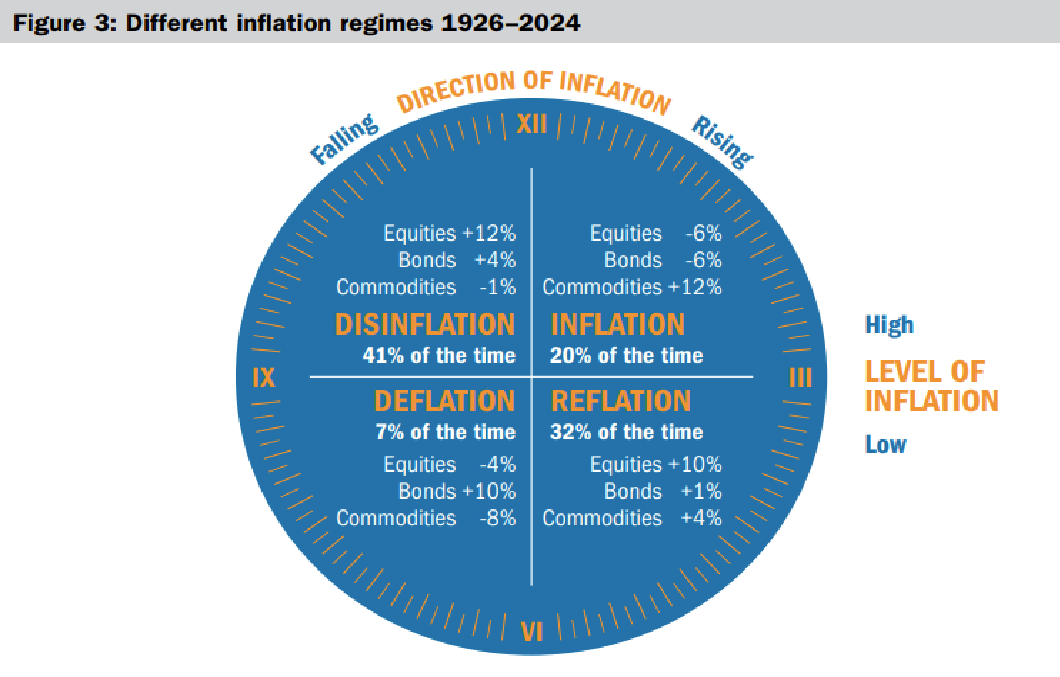

Ruffer’s head of investment strategy, Teun Draaisma, co-authored a seminal academic paper on how various asset classes perform in different inflationary regimes. Using nearly 100 years of US, UK and Japanese market data, the authors defined four different inflation regimes, based on both the level and the direction of inflation. To qualify as a regime, the criteria had to be met for a minimum of six months.

The authors measured asset class returns in each defined regime. Their findings can be used to create a new, inflation-centric investment clock (figure 3).

Starting on the bottom right (between three o’clock and six o’clock), inflation is low but rising; the economy is growing, but not overheating. As you might expect, growth assets such as equities perform strongly, with some support from bonds as income assets. On the bottom left (from six o’clock to nine o’clock), inflation is low but falling, which often marks a recession. Bonds kick in to provide protection as interest rates are likely falling, while equities are down.

In both these lower quadrants, a blend of bonds and equities works well. When the level of inflation is low, building a diversified portfolio is straightforward.

And we can then apply these findings to investors’ historical experience. For most of the 1990 – 2020 period, when inflation overwhelmingly remained below 2%, a typical 60:40 portfolio of equities and bonds performed well. But this means most people working in the industry today have only ever invested in a world that looks like the bottom two quadrants of the inflation investment clock. Crucially, the assumptions of modern portfolio construction are also largely based on data from this period.

Now look at the top two quadrants. On the left (nine o’clock to twelve o’clock), inflation is high but falling – as happened in 2023. This is good for both equities and bonds. Their correlation is positive – helpfully so for 60:40 portfolios. But, on the right (twelve o’clock to three o’clock), inflation is high and rising. Both bonds and equities fall sharply. Here, the positive correlation really bites, as many investors with memories of 2022 will confirm.

The good news? The data from the study shows that commodities – notably both industrial and precious metals – can offer protection to portfolios when inflation is high and rising. In addition, more recent data and investor experience point to other assets, such as derivatives, which can provide an uncorrelated return stream and thus help bring diversification to a portfolio. Fortunately, in a disinflationary environment, the diversifying assets in the study (commodities) did not cost too much, yet they were an essential portfolio component in the inflationary environment.

Movement required

These findings emphasise the reality that portfolio construction in the new regime is less straightforward than before. It will require more complex instruments, but these can be used to great effect.

The truth is that different types of diversifying assets work at different times. Allocations need to be managed dynamically, just like the broader portfolio.

For example, Draaisma’s analysis showed that gold delivered the best average return in inflationary regimes. However, it delivered positive returns only two thirds of the time. So gold can deliver some protection, but it’s not like clockwork.

Clearly, the level and direction of inflation, and where we are in the economic cycle, are not the only drivers of markets. Liquidity is another. Whether market structures are fragile or robust are also important considerations. But inflation remains one of the clearest risks, and the investment clock offers a helpful way of thinking about this.

What’s interesting is, after a period of falling inflation, the market is now betting the clock has stopped ticking. Can that really be the case? Will the re-acceleration in US inflation stop in time to leave us in a bullish, reflationary regime? Or are we heading for another inflation period that spells trouble for conventional assets? We can’t be sure just yet, but conviction is high that we are more likely to find ourselves in multiple different time zones over the coming years.

The great escapement

Around 1275, a willingness to adapt and experiment led to the invention which paved the way for modern clocks: the verge and foliot escapement. This used a saw-toothed wheel and a rod with projecting plates (the verge) to control the rotation of a horizontal beam with weights on either end (the foliot). Their combined operation moved one tooth at a time, so that the clock’s mechanism advanced steadily. This was the brain behind the clock’s face.

Given inflation’s return and the high valuation of US equities (which account for two thirds of the global index), we believe today’s portfolios also need controls to help them progress smoothly. To a peaceful tick tock, rather than the ringing of alarm bells.

The problem is solvable. But investors will have to be more ingenious and imaginative – willing to allocate to an expanded range of assets and then manage them dynamically.

Jasmine Yeo is a fund manager at Ruffer.

Charity Finance wishes to thank Ruffer for its support with this article.