Pity the poor trustees of significant charitable endowments today. How difficult it must be for these usually unpaid and often unrewarded guardians of monies bequeathed ages ago in furtherance of specific philanthropic aims to navigate their way through today’s financial markets. To work out whether the strategy they have set their investment manager is going to achieve what their charity needs and wants. Having been involved in many a beauty parade over the years, I genuinely feel for the boards of trustees trying to make their decision between a group of doubtless equally compelling propositions, even when helped by a consultant.

First, in this information-driven age, the availability of so much choice must be confusing, particularly to the non-professional trustee. Secondly, despite the blandishments of the regulator, the method and manner of presenting performance and cost information requires some significant technical explanation on the part of the provider. Finally, there is the nagging sense that with all that has happened, and is happening, in this bonkers world we inhabit, that we must surely be on the cusp of a massive inflexion point which requires a radical change of direction in the way an endowment should be managed.

In this situation, it might be worth stepping back and reviewing some of the proven disciplines that have served to keep trustees on the straight and narrow and preserve the capital of their charities.

The first must be an appreciation and understanding of intrinsic risk. Risk in the abstract means different things to different people. But in terms of investment risk, often a good starting point is the benchmark for what is termed the risk-free rate of return: the yield on the ten-year government bond. In modern history, the government has never defaulted on repayment of a debt security issued in its name because it is secured on future tax revenues that are deemed inviolate, hence the term gilt-edged. Until recently, the ten-year gilt languished on a yield of around 0.5%; at the time of writing (November 2021) it has spiked up to around 0.9% on inflation fears. However, if this represents the risk-free rate, how much additional risk is an investor to assume in order to achieve a higher return?

This leads neatly on to the second discipline, which is the need for a focus on the preservation of capital. Capital preservation at its most basic means preserving the real or purchasing power of capital, in other words, ensuring that it keeps pace with inflation. In times of rising prices, inflation, that thief in the night, has proved a serious destroyer of the real value of capital. Whatever else a charity requires from its endowment, preservation of the capital originally endowed or subsequently raised must be a priority for any board of trustees. So now with inflation rearing its ugly head once again, trustees must hope their manager has been quietly building protection against inflationary pressures into their investment portfolio in anticipation. As with any insurance against a peril, buying cover once it has become manifest is either very expensive or impossible.

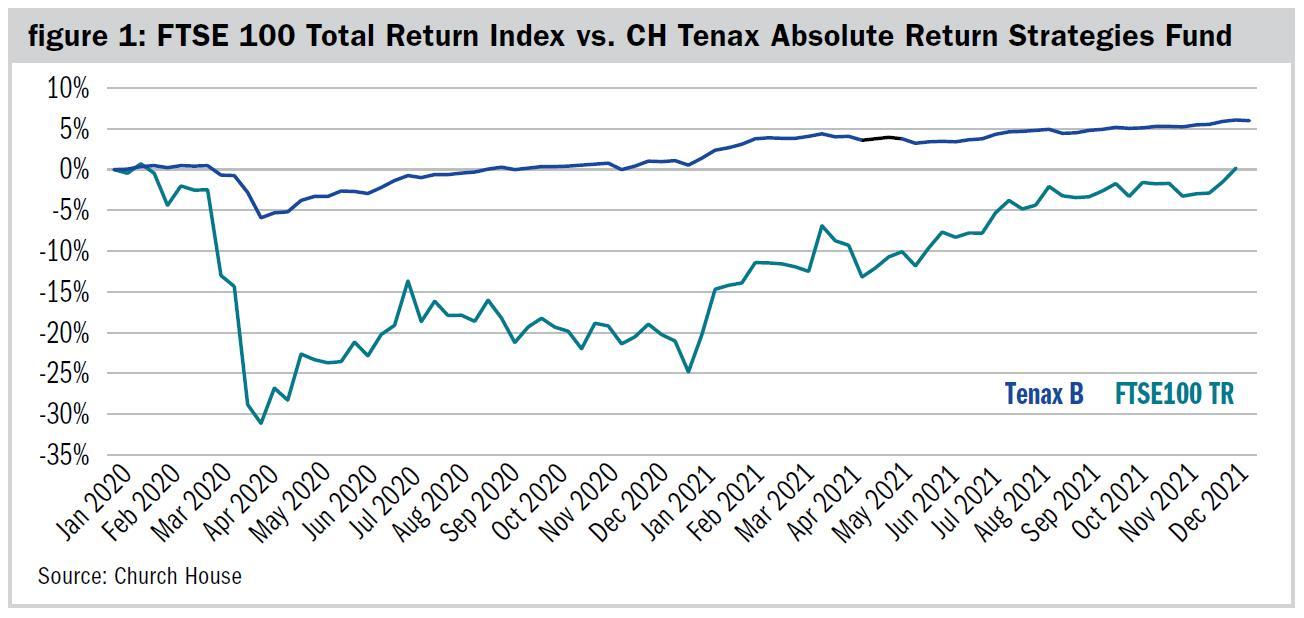

Figure 1 shows a recent example of capital preservation during, and immediately after, a market crisis. The FTSE 100 has, in total return terms, only recently recovered to where it was before the Covid-19 crisis first hit last March. An absolute return strategy, such as that followed by the CH Tenax fund with capital preservation as its core priority, had recovered any losses by early July.

The third discipline is patience and an appreciation of the value of time. Charitable endowments with a very long or infinite timescale should not be concerned with short-term issues or worse still, letting recent performance guide decisions. How many trustees fall into the common trap of driving by looking in the rear-view mirror? Charity investing, by definition, should be long term and measure performance by decades, although it is only natural for trustees to get rattled by the constantly negative news flow, and the many doomsters and gloomsters who comment on markets. In particular, trustees may worry about how and when to commit new cash to their charity’s investment portfolio. But for the genuinely long-term investor like the charity, the old adage of time in the market rather than timing the market has invariably proved true. Of course, a good investment manager will always seek to minimise timing risk by averaging new money into the market over time to smooth the effects of market fluctuations. But their ultimate aim should be to get the money into the market as soon as possible so as to secure that vital investment traction – in particular the harvesting of those all-important income returns – rather than trying to finesse the timing decision.

The fourth lesson must be to remember the magic of compounding, termed the eighth wonder of the world by Albert Einstein. A 7% annualised return may not sound that exciting to the casual investor, but if you tell them that their investment will double in approximately ten years’ time then it becomes rather more impressive. The rule of 72 is a great standby in this context: simply divide 72 by the percentage annualised growth rate to find out how quickly an investment will double. Active reinvestment can significantly reduce this.

The fifth and final lesson must be asset allocation, or in plain terms, getting the right eggs into the right baskets. In its simplest expression, asset allocation is about deciding the optimal mix between the four principal investable asset classes of cash, property, bonds and equity. At the moment, there is much comment in the media about inflation and therefore the unattractiveness of bonds with their fixed income yields forming so large a portion of their total return. While it is true that bonds have enjoyed extraordinary conditions because central banks have been the chief buyer underpinning the markets for these securities, it is rarely the case that bonds do not form some sensible part to play in a diversified portfolio. For example, index linked bonds should form significant protection against inflation and rising interest rates.

In conclusion, charity trustees need good advice and firm guidance when setting their strategy. This, of necessity, requires good communication with and a high level of transparency from an investment manager who is going to take the time and trouble to explain the whys and wherefores of their portfolio so that they are always in a position to account to their stakeholders for the risks that are being assumed in the endowment. Therefore, the relationship between an investment manager and the trustees is paramount.

James Johnsen is a director at Church House

Charity Finance wishes to thank Church House for its support with this article

Related articles