Kirsty Weakley argues that if charities don’t understand what their technology partners are doing, they risk damaging trust in the sector.

The story about a fake charity app that was claiming to help Maltese charity, Migrant Offshore Aid Station (MOAS) has the potential to do serious damage trust in charities around the world. I Sea was launched last week, promising users that by checking a specific plot of ocean for migrant boats they could quickly alert the charity to anyone in trouble and that a rescue boat would be dispatched.

It all sounded great. Sadly it was too good to be true, and no one has emerged with much credit here.

Shortly after it launched, positive stories about the the app appeared across several titles last week, including Reuters, the Evening Standard and specialist technology title Wired. But by yesterday serious concerns were being raised within the tech community that the app could be a scam designed to generate publicity for the advertising agency involved and was actually helping anyone. It has now been removed from Apple's app store.

Leaving aside the questionable premise of the app – how exactly are users supposed to differentiate between boats full of refugees that may be in need of assistance, and regular fishing boats?- both the charity and the advertising agency have behaved disgracefully.

The agency in shamelessly seeking publicity for a product that could not work, and hoodwinking users into thinking that in a few spare minutes they could help rescue people in trouble. And the charity for endorsing and supporting the app without understanding how it worked or what the implications are.

While Grey for Good, the philanthropic arm of a Singapore-based advertising agency, has since admitted in a statement that the a is still in a “testing period” and that the images were not “in real-time”, this looks of some hasty back-peddling from people who have been caught out.

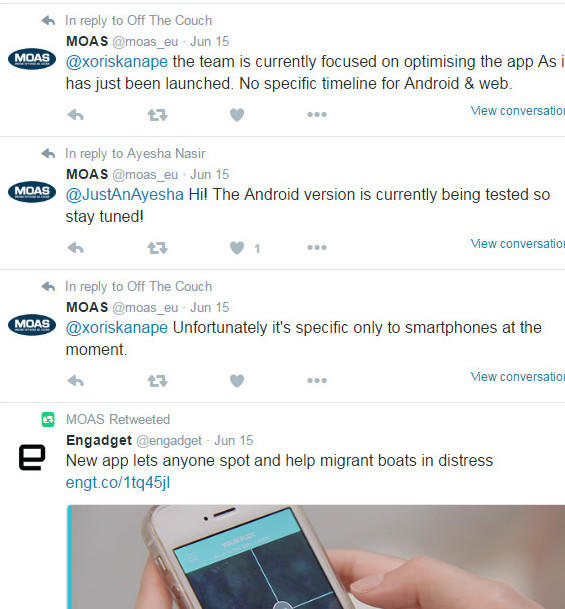

The charity, meanwhile, has remained almost silent on the issue, in contrast to its behaviour last week.

Last week MOAS has provided quotes to publications writing about the app and has been retweeting stories about it and replying to comments from people asking when the app will be available on other platforms on social media.

So it came as a surprise when a spokeswoman for the charity said she was unable to respond to the concerns yesterday, saying that: “Technology questions are not our area of expertise.” Instead she directed me to Grey for Good, the agency.

Failing to offer any adequate explanation is unacceptable, as is hiding behind the fact that it had been developed by an advertising partner. No one expects the charity to understand every line of code, but you could reasonably have expected them to ask more questions before endorsing the app.

Once it became apparent that the app was not all it claimed to be, the charity should have immediately responded on its own channels and launched an investigation to find out how it appeared to endorse a fraudulent product. By not doing so it is almost complicit in the scam, which could deter people from trusting and engaging with other crowd sourced projects in the future.

When done well these kinds of projects can be transformative. For example Cancer Research UK was able to harness the power of the crowd to analyse an enormous gene data much more quickly than scientists in its labs could have done after developing a smartphone game, Genes in Space.

Why UK charities need to care

So why could this damage charities here? This was a charity based in Malta who had worked with an agency in Singapore.

Because the world is more connected than ever. Many of the news reports appearing in UK-based publications did not mention the charity’s location, and I very much doubt that average Evening Standard readers automatically check the Charity Commission register when they read about an organisations they’ve never heard of before.

I’m not suggesting that charities or regulators in the UK should abandon initiatives to help the public understand and celebrate the work that the sector does because it could be undone by a rogue charity in Outer Mongolia.

But it underlines the increasing the need to work across borders and the importance of being aware of the global reach that ‘brand charity’ has.

Update: 2pm

MOAS has issued a statement saying that it has discontinued its relationship with Grey for Good.

"MOAS is a charity dedicated to saving lives at sea, it does not develop apps. While we provided information on the reality of operating at sea to Grey for Good, we did not develop the I SEA app. We support the idea of testing new technologies and innovations that aim to save lives at sea.

"As a global NGO that rescues people at sea, we are approached by countless number of companies and innovators who would like to contribute to our cause. We make it a point to try and give advice according to our own experience in the field of search-and-rescue and in line with our humanitarian principles.

"Grey for Good is a well-intentioned pro bono arm of a globally known ad agency. When they approached MOAS with the idea of an app that could crowdsource the ability to identify vessels in distress we provided input based on their real world experience. Among that advice was the need for real time input to save lives. Their goal was to feed MOAS relevant information and engage users in the idea of saving lives.

"We were dismayed to discover that real time images were not being used. We have since discontinued our relationship with Grey for Good and spoken candidly about our disappointment to the media.

"Our mission remains that of carrying out professional search-and-rescue efforts along the world’s most dangerous border crossing – the sea. We will continue to work closely with supporters and continue to be open to new ideas that can save lives. We would like to thank all those who have expressed their support and continue to believe in our work."

See also