In a world where it is deemed rational to lend money to the UK government for ten years and receive 1 per cent for your efforts, it will not be surprising to hear that we do not expect government bonds to offer much of a return to investors.

Waverton invests globally so we can look overseas for other opportunities than just the UK, but of the major economies in the world, only in the US are government bond yields above 2 per cent.

In our long-term strategic work, we estimate that a global bond portfolio, including corporate bonds, will return just 0.5 per cent above inflation over the next five years.

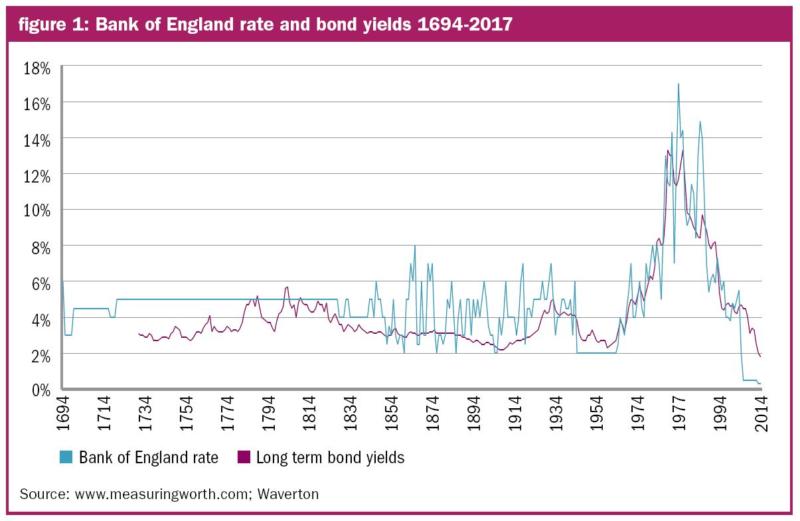

Conversely we expect global equities to return CPI +4.5 per cent. These calculations take into account the current valuation of the main asset classes and compare them to the valuations that we expect to be sustainable in coming years. When it comes to future government bond market returns, the challenge is that interest rates have never been as low as they are today. Prior to moving its base rate to 1.5 per cent in January 2009, the Bank of England had never set rates lower than 2.0 per cent in its 324 year history.

In addition to moving policy rates, the Bank of England, like many central banks, has been buying bonds in the open market. The effect of this has been to help compress yields across the duration curve meaning that long-term interest rates have also been dragged down to record lows.

So, as figure 1 shows, long-term bond yields (here shown as a consistent series that equates to today’s 30-year gilt) have, like the Bank of England’s policy rate, never been at today’s levels.

It would, however, be dangerous to say that because they are at these levels, they cannot go lower. Policy rates are negative in Japan and in much of Europe. Bond yields are lower than UK gilt yields in Japan and much of Europe too. Indeed ten-year bond yields are negative in Switzerland and have been negative at times in Japan and much of Europe.

Nevertheless, it is reasonable to conclude that owning government bonds at today’s levels will only provide a good return if the historically unique situation continues for long enough to become a new normal of extraordinarily low interest rates. This would likely be during a period of nervousness about the economic outlook that produced a sell-off in the equity market.

Does that mean investors should shun exposure to government bonds altogether? We think not. In many of the portfolios we manage, government bonds are used for risk mitigation purposes. Despite the low rates on offer, when the equity market falls we expect gilts, along with US treasuries and German bunds, to attract investor capital as a safe havens.

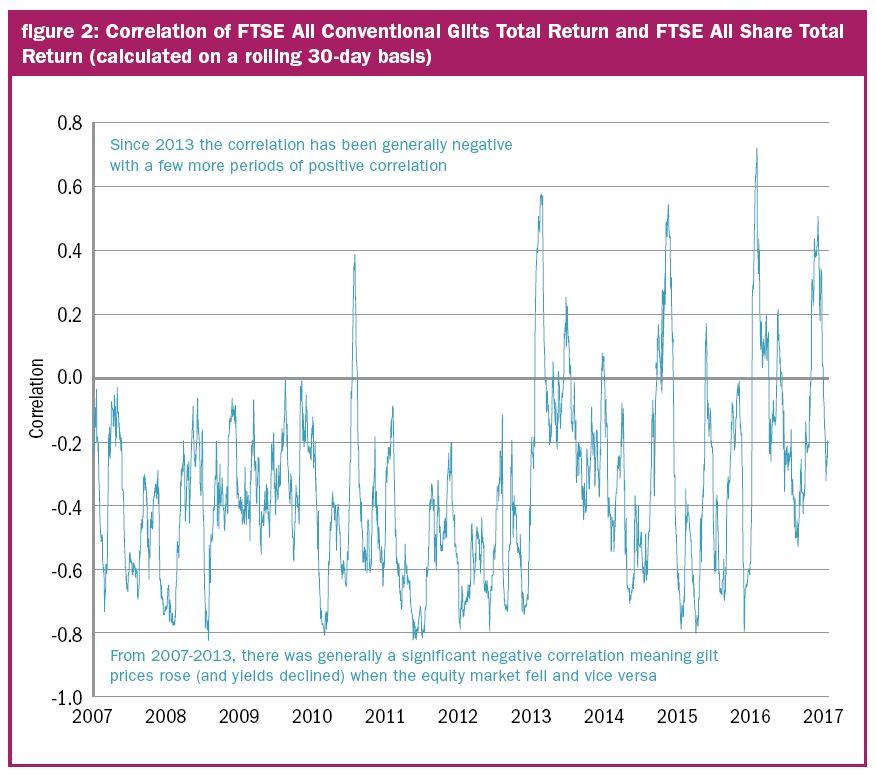

We can monitor the efficacy of this strategy by looking at the correlation between the total return of bonds versus the total return of equities. If we are right, then the return from owning bonds will be positive when the return from owning equities is negative.

In other words, the correlation between bonds and equities will generally be negative. Figure 2 shows the correlation between the FTSE All Conventional Gilts index and the FTSE All-Share (both total return) since the beginning of 2007.

In the period between 2007 and 2013, the correlation between bonds and equities was negative virtually the whole time. In other words, when equities fell, bond prices rose, and vice versa. The only exception was in November 2010, but fortunately that was a relatively small equity market correction of 2 per cent over the month.

There are 2,761 trading days in figure 2. The rolling 30-day average of the correlation has only been positive on 299 of those days (11 per cent of the days).

However, it is true to say that since 2013 the relationship has not been quite as reliable. Of the 1,225 trading days since January 2013, the correlation has been positive on 280 of them (23 per cent of the days). So let’s look at the periods when the correlation has been positive in more detail. Remember, we are owning bonds for the purposes of providing us with some positive returns to offset falling equities. So we want the correlation between the two to be negative when equities are declining.

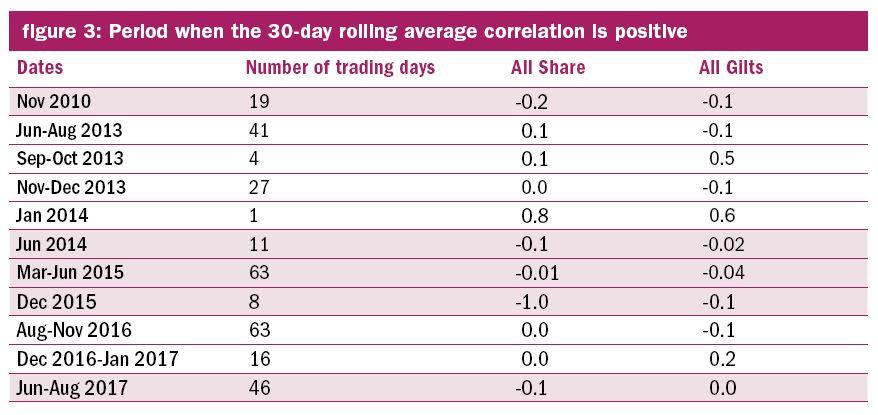

Figure 3 shows the average daily percentage change of equities and of gilts in each of the periods of positive correlation. There are five periods highlighted when the equity market declined and bond prices also declined. These are periods when our rationale for owning bonds did not work.

Only one of those periods was in the period from 2007 to the end of 2012. During those six years, on only 1 per cent of trading days were equity prices and bond prices positively correlated, and that happened to coincide with the small equity market wobble in November 2010. Bonds were close to a perfect hedge over that whole period of time. Even since 2013, when there have been four periods of declining equity and declining bond prices, those periods represent just 10 per cent of the trading days.

Our conclusion from the above is that for the vast majority of time over the last decade, bonds were a very good hedge to an equity investor. Therefore we continue to see a diversified portfolio offering most investors advantages even in a world where the level of interest rates makes the likely returns from owning bonds lower than it has been in recent years.

William Dinning is head of investment strategy and communications at Waverton

Charity Finance wishes to thank Waverton for its support with this article