Nick Aldridge offers a comprehensive overview of the current state of the tax relief cap debacle.

The cap on tax relief for charitable donations, proposed in the 2012 Budget by UK Chancellor George Osborne, has galvanised rapid and forceful opposition from charities and philanthropists. The cap will hit a large number of high-value donations, dramatically decreasing their value to charities and increasing their cost to donors.

The response from government has been even more worrying than the announcement, both in terms of the technical clarifications made, and its generally negative tone about charitable giving. This post aims to clarify some of the more confusing aspects of the cap and its effect, and explode a few of the myths recently promoted in its defence.

How did this happen – isn’t the government supposed to be promoting charitable giving?

Up until now, the government seemed to be strongly in favour of charitable giving. One of the key planks of the “Big Society” agenda was to encourage greater public engagement in volunteering and charitable giving. A green paper (to which I contributed) and a white paper on giving were published. Last year’s Budget provided a tax break for people who donate 10 per cent of their legacy to charity. There have been moves to simplify the process of claiming tax reliefs for smaller charities. A Philanthropy Review group, whose members worked closely with the government, recently called for tax relief on donations to be extended.

On the other hand, HMRC and HM Treasury have a history of making it harder for charities to operate, with the supposed aim of catching those committing tax fraud. For instance, the recently-introduced 'fit and proper persons' guidance suggested that charities ask all their trustees to sign declarations saying they’re not tax criminals, at a likely cost to the sector of more than £20m. In the first 18 months, these rather patronising measures did not result in the refusal of a single tax relief claim, and (according to HMRC) led to “a couple” of people leaving charities.

The decision on the cap was almost certainly made at the last minute by the Treasury alone, without consulting ministers who are working to promote and encourage charitable giving. It seems to have been part of moves to increase the tax burden on the richest in society. Nick Hurd, the minister for charities, did not appear to have been closely involved in developing the policy:

Sir Nicholas Hytner, from the National Theatre, said the changes also blindsided the Culture Secretary, who has been working to encourage donations to arts organisations. He said they “came completely out of the blue and I have to say I think it came completely out of the blue for the Department of Culture as well. I just don’t believe they were included in these discussions.” (The Guardian)

How much is at stake, and when?

The wording of the proposal is as follows: “The Finance Bill next year [will] apply a cap on income tax reliefs claimed by individuals from 6 April 2013. For anyone seeking to claim more than £50,000 in reliefs, a cap will be set at 25 per cent of income (or £50,000, whichever is greater).” (HMRC website). Since the gift aid claimed by charities will count towards the limit, any donations over £40,000 will be hit by the cap.

There is no data available on donations over £40,000, but we can get a feel for their scale by looking at the largest donations. According to a recent Coutts report, 174 donations worth at least £1m were made by UK donors or to UK charities in 2009/10, with a combined value of £1.3bn. CAF reports that the top 100 donors last year gave £1.6bn. That is a highly significant amount – around 15 per cent of total donations by value, and doesn’t include any donations between £40,000 and £1m, which will also be affected, and might be even be greater by value.

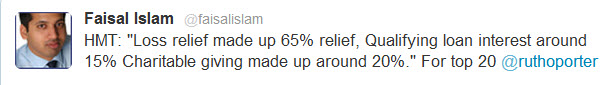

Of course, the cap affects all uncapped tax reliefs, not just relief on charitable donations. So a donor who was already investing £50,000 in an Enterprise Investment Scheme, for example, would not be able to claim any tax relief at all on donations to charity. This aspect of the cap shouldn’t be neglected: according to HM Treasury charitable donations only account for 20 per cent of uncapped tax reliefs claimed by the richest 20 people affected. So many of them will have exhausted their tax reliefs through their own investments or business losses, which may be far harder for them to unwind, give up or reverse than their highly discretionary charitable donations.

But can’t rich people just give the same amount, after paying their tax?

Some will – the point is that a certain level of financial sacrifice from a donor (say £1m) will be worth far less (up to 50 per cent less) to the charity benefiting. Many large donors might be motivated, at least in part, by the perceived impact their money will have, in relation to the cost to them of giving it up, and they will give less as a result. Some clear examples are worked through by More Fundraising Consultants.

Survey data supports this hunch: the Charities Aid Foundation polled 183 donors who gave more than £50,000 per year. Some 37.5 per cent said they’d reduce their giving because of the cap, and two-thirds of that group said the reduction would be significant. A total of 83 per cent expected giving generally to be impacted.

Some charities will be affected disproportionately: the Christian philanthropic charity Stewardship says that 20 per cent of its £55m income comes from donations of more than £50,000, and one major donor has said he’d reduce his giving by 75 per cent. Capital appeals by charities building anything from cancer treatment centres to art galleries will be worst hit. As Sir Stephen Bubb commented on Newsnight last night, up to 80 per cent of the funding for such projects comes from major donors.

Philanthropists are already saying the cap is affecting their own gifts, and those of others. Last night Dame Stephanie Shirley, who has given away £60m herself, published an open letter to the Prime Minister criticising the government’s ‘cack-handed assault on philanthropic giving’. She said: "‘These plans are already discouraging major giving, with donors informing charities privately of their intention to put on hold plans to give five-, six- or even seven-figure sums.” One of Stewardship’s donors gives 90 per cent of his £1m income to charity each year – this would be impossible if he were then hit with a tax bill far exceeding his remaining income.

But the rest of us don’t get tax relief on donations, why should the rich?

Anyone with an income can get tax relief on their donations through the gift aid scheme. In the UK, however, most people don’t complete tax returns, so claiming the gift aid for themselves could be too laborious, particularly for smaller donations. Instead, the tax relief for basic-rate taxpayers is claimed directly by the charity, so a £100 donation to charity will cost a basic-rate taxpayer £80. A higher-rate taxpayer paying 40 per cent tax can reclaim the difference – a further £20 – off their tax bill.

Who actually gets the tax relief isn’t as important as it may appear. The point is that a certain cost to the donor (£60 or £80) is worth more to the charity (£100). People who are basic-rate taxpayers and want to claim tax relief “for themselves” can do so through payroll giving, through which donations are deducted before income is taxed.

The important principle is that people shouldn’t be taxed on income they’ve forgone by giving it away for the public benefit. While the gift aid scheme is complicated, with reliefs claimed partly by charities and partly by donors, it’s this key principle that’s under attack.

Well, don’t the richest people give much less than the poorest anyway?

This claim is frequently made by ministers and many in the fundraising sector, but it doesn’t really stack up. The most authoritative source I’ve found is a press statement from Bristol University, which said “poorer donors are still more generous than richer donors in terms of the proportion of their budgets they give to charity”.

In one, fairly narrow sense, the claim is true. According to the report, of those who give to charity, the poorest tend to give a higher proportion of their household expenditure. The bottom 10 per cent of donors by household expenditure give 3.6 per cent to charity, while the richest 10 per cent give only 1.1 per cent.

Unsurprisingly enough, however, the richest people are far more likely to be donors in the first place. Almost half of the richest 10 per cent give something to charity, while only 1 in 10 from the poorest 10 per cent do so. So although we can claim that the poorest give more to charity, this is to ignore the 90 per cent of them who don’t make donations.

| % Given (all households) | % Households that give | % Given by those who give |

Poorest 10 % | 0.40 | 10.70 | 3.60 |

Richest 10 % | 0.50 | 47.20 | 1.10 |

No doubt many richer people can give more, and many of the poorest households can’t afford to give anything. The point is that we are not going to encourage the richest to support charities by presenting those who give as selfish tax-dodgers. Instead we should be focusing efforts on the 50-60 per cent of rich households who give nothing to charity, and explaining how it can be positive, enjoyable, and highly rewarding.

Participation in giving among the richest 10 per cent has increased slightly in the past 30 years, while giving from the poorest has decreased (from 17 per cent in 1978). It would be a shame to reverse this by questioning their motives.

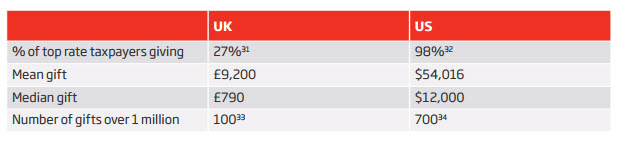

But don’t they give less than rich people in the US, which has a cap on donations already?

As the Philanthropy Review noted, rich people in the UK do appear to give much less than in the US, which has a cap on tax relief from donations. However, the US cap is set at 50 per cent of income for donations alone, which is far more generous than the proposed UK cap of 25 per cent for all uncapped reliefs. Other aspects of the US system are far more generous, in particular concerning the gift of items to charity.

As Karl Wilding of the National Council for Voluntary Organsations (NCVO) noted: “If HMT are suggesting that we adopt the US system of tax reliefs I think many people would snap their hand off! The system is totally different – simpler and far more generous than the current UK system, never mind the proposed scheme.”

What does the government have to say for itself?

In response to early criticism HMRC made some infuriating and irrelevant comments. Since then, things have got rather worse.

Back on 2 April, a spokesman for HMRC told civilsociety.co.uk that: “The bulk of charitable donations come from basic-rate taxpayers, not from the super-rich.” This is obviously true: most people aren’t super-rich, and can’t make large enough donations to be hit by the cap. However, it’s completely irrelevant – large donations (by definition) are disproportionately important, and those are the donations at stake.

HMRC also said “the cap was not aimed just at charitable tax reliefs, but at a whole range of reliefs”. Again, this is irrelevant and disingenuous. If the government really doesn’t want charitable tax reliefs to be affected, then they shouldn’t include them. It really is that simple.

More recently, the government has turned on donors and charities. In perhaps the most damaging intervention since the announcement, the Prime Minister’s spokesman said yesterday said that multimillionaires are donating to charities which do little work for good causes [primarily] to “wipe out” their income tax bills.

First, it’s insulting and silly to claim large donations are motivated mainly by tax relief. In fact, this is arithmetically impossible – donors must give away much more than the claim back, so there’s nothing to be gained financially by doing so. As John Low, chief executive of the Charities Aid Foundation, said: “Philanthropists who make large donations give away far, far more than they could ever claim in tax relief. That money goes to fund projects for the public good, such as medical research and help for the most vulnerable in society.”

The indignation from major donors is clear from quotations in the letter from Dame Stephanie Shirley: “The government says that it is pro-philanthropy, and then absurdly limits the amount people can claim against their income. How do they imagine that any future capital programme will succeed without major donations? Do they think people like me who give money are motivated by tax avoidance?”

But what about these bogus charities?

As the Daily Mail reported, No.10 and the Treasury haven’t previously been good enough to share their intelligence on bogus charities with their regulator: “The government’s claims that there is a widespread problem with the wealthy funnelling cash to bogus charities was quickly shot down by the Charity Commission. The watchdog, which registers charities and investigates claims of wrongdoing, said it had never been contacted by the Treasury about the issue.”

It’s important to note that any such bogus charities are breaking the law. All charities have a legal obligation to use their assets (including donations) to promote their charitable purposes and benefit the public. All their decisions must be made in the interests of the charity and its beneficiaries. Any significant complaints about particular charities should be investigated by the Charity Commission, which takes action and publishes the results of its work. So if the government genuinely has any evidence that charities are being abused by wealthy donors, they should report them to the regulator. To coin a phrase, put up or shut up.

As Conservative MP Zac Goldsmith succinctly put it:

Further, the government already has extensive tools to deny tax relief to bogus charities. As Stephen Lloyd, partner at Bates Wells and Braithwaite, has said: “You only get higher-rate relief when you put in your tax claim, so if the Revenue doesn’t like the look of your donation to, say, the ‘widows of the Mafia’ charity in Palermo, they can simply say ‘we’re not going to give you this relief, we don’t like the look of it, it doesn’t pass any of the tests, sue us if you want to’.”

In short, if bogus charities are claiming large tax reliefs for themselves and their donors, let’s close them down. But to suggest this is widespread, and use it as a reason to punish thousands of well-known and entirely legitimate charities, is unfair and will be highly damaging.

So what now?

While the government is planning a consultation on how to limit damage from the cap, the obvious move is simply to exclude charity donations from the cap, and do it quickly, before more large donations are cancelled. You can join the campaign against the tax relief cap at http://giveitbackgeorge.org/.

You can follow some of the key people, behind the campaign - Karl Wilding and Rhodri_H_Davies on Twitter, or add to the conversation using the #giveitbackgeorge tag.