It’ll come as no surprise to you that I think social enterprises are pretty wonderful organisations. As the chief executive of the School for Social Entrepreneurs (SSE), I will happily talk about the benefits social enterprises and community businesses can bring to a place and to people. And in fact I do, a lot.

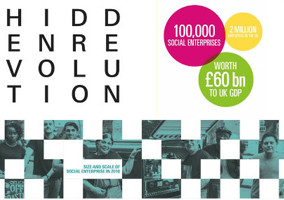

Social enterprises have been making headline news recently. There are more of us than ever before and we’re growing. The UK is viewed by other countries as a pioneer in social enterprise, and a leader in the development of social investment and social value. The latest research from Social Enterprise UK shows there are around 100,000 social enterprises in the UK, contributing £60bn to the economy and employing two million people.

So I should be excited, right? And I should be proudly telling you about the number of businesses in our sector that turn a profit (around 70 per cent were profitable or broke even last year). But I’m nervous, because the increasing confidence in social enterprise is also fuelling a myth – one that makes it incredibly difficult for the next generation of social entrepreneurs to move their business ideas from the start-up space and into the established arena. And that is the myth that all social enterprises can and should become wholly sustainable (i.e. make all their money from trading, without any need for grant or donations).

Importance of grants

Yes, there are thousands of social enterprises out there that make it all on their own, but there are still a significant number of organisations that rely on grant funding to keep them up and running. And I think those organisations, and those funders, should be really proud of the grant that they receive and give.

I’d like to celebrate the fact that grants remain part of the mix for social enterprises, particularly for those at earlier stages of their life cycle; 37 per cent receive a grant from a public sector body, and 33 per cent receive grants from other organisations.

It also makes perfect sense – a level of grant funding is essential for many social enterprises. A third of social enterprises in the UK work in the most deprived communities, and 44 per cent employ people who are disadvantaged in the labour market - such as ex-offenders, people with disabilities, military veterans and homeless people - according to Social Enterprise UK’s latest research. This is precisely why many of these organisations need some income from grant: to indemnify the cost of helping people in need.

There’s an amazing café, shop and garden that forms part of the offer that the Buzz Lockleaze team run in Bristol; it’s a locally born social enterprise that offers employability training and opportunities for unemployed people, helps others to set up enterprises and improves access to healthy, affordable food. It’s doing really valuable work, but it’s also never going to be as profitable as the nearest Costa Coffee. That’s not because it’s a bad business, but because their social purpose – supporting people in need – is at odds with the playbook of for-profit capitalism. Creating social impact is expensive and not exactly conducive to maximising profit. But that’s the point: for social enterprises, social impact is more important that profit. To me it would make perfect sense that Buzz Lockleaze receives some grant-funding.

Diverse income streams

Of course, I don't think grants should be the only source of income for social entrepreneurs – they are entrepreneurs, after all. Much of what we do at SSE is supporting people to learn how to diversify and rebalance their income streams. Often, that means moving away from grant-dependency, to generating more income from trading goods and services. We recognise that grant provides an essential helping hand, but we’re focused on incentivising more entrepreneurial behaviours and supporting trading activity. That’s why we developed Match Trading™.

Match Trading is a new model of grant funding that pound-for-pound matches an increase in income from trading. By rewarding sales growth, Match Trading incentivises social organisations to develop their trading base, so they can build stronger futures. We’re running programmes with pioneer partners Lloyds Banking Group and the Big Lottery Fund, and programme partner Power to Change, to explore the impact of this new type of funding. The initial results have been really positive. The numbers who have completed programmes are still small (40 organisations were given access to a learning programme and Match Trading grants of £7,000-10,000), but typically they have increased their income from trading by around 90 per cent compared to their previous financial year (calculated by median).

We’re now working with a task force of individuals from the UK’s leading trusts, foundations, social-sector bodies and the government, to consider how we develop the Match Trading model. We want to test how it can be best used to support more social sector organisations. Over five years, Match Trading grants will be used by at least 600 social enterprises, charities and community businesses.

In the recently published Civil Society Strategy, the government spoke about "Grants 2.0". I think we should explore new and innovative ways of administering grant funding, such as Match Trading. Then we can support community businesses and social enterprises – often operating in the most challenging markets and poorest communities - to create more (but not always wholly) sustainable futures.

Alastair Wilson is chief executive of the School for Social Entrepreneurs. He became a social entrepreneur when he joined SSE’s very first cohort in 1997, in Bethnal Green, London.

|

Related articles