This month, the Bank of England increased interest rates for only the second time in a decade, to 0.75 per cent. The rationale behind doing so continues to be scrutinised, but the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) of the Bank of England remains focused on one thing; the rate of inflation in the UK and more specifically, the government’s target of 2 per cent.

A change in the policy rate is subject to a majority vote of the committee members and in a quarterly report they provide a collective expectation of the forecast for inflation. Importantly, this committee, like the Bank of England as a whole, remains independent from the British government and is free to make monetary policy decisions as it sees fit in order to meet the 2 per cent inflation target.

Outside the UK there are real-life instances of the independence of central banks being challenged. In extremis, Erdogan the President of Turkey has taken ownership of the future of monetary policy decisions, leading his country down the precarious path of a devalued currency and contained interest rates. This approach tends to leads to a highly inflationary environment. Meanwhile, how long the US Federal Reserve will retain its independent mandate under the Trump presidency is also being questioned, with tweets and threats of interference making change a foreseeable reality.

In the UK, we have seen a glimmer of how fractious the relationship between the Bank of England and government might become. Many have criticised the current governor of the Bank of England, Mark Carney, for opining on the potential economic implications of Brexit; for many a move too far into the political sphere.

Meanwhile, Jeremy Corbyn’s proposals for a “People’s QE” would fundamentally compromise the independence of the Bank. In effect, people’s quantitative easing would involve the government instructing the Bank of England to print money in order to purchase government debt created to fund the likes of infrastructure projects, thereby muddying the monetary and fiscal policy split between the independent central bankers and that of the government.

Potential mistakes

Amidst increasing tensions within the Conservative party, stuttering Brexit negotiations and headlines questioning Jeremy Corbyn’s integrity as a future prime minister, direct questions as to the future of Bank of England’s independence has remained low on the agenda. What’s more, sterling weakness as a result of Brexit uncertainty has increased inflationary pressures at the same time the economic data has suffered at the hands of extreme weather. The criticism of a rate rise at this juncture, however, is that the political cliff as regards negotiations with Brussels is likely to become more and more precipitous.

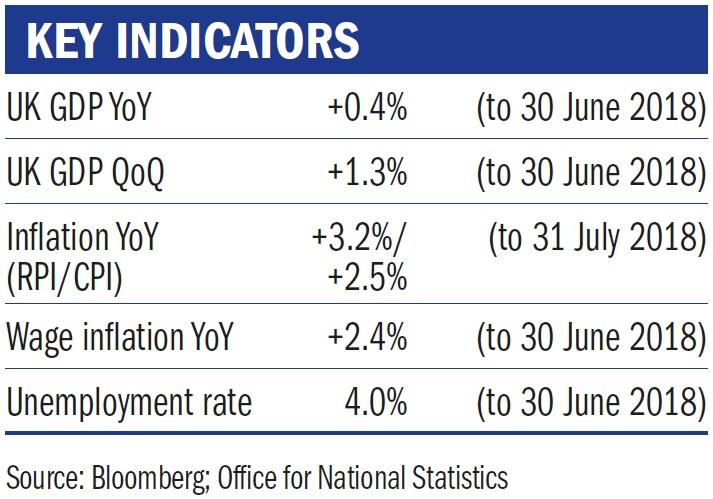

But the MPC has to play a balancing act; their recent action is set against the bank’s mandate which refers to the inflation rate currently sitting at 2.5 per cent for the Consumer Prices Index (CPI) and 3.2 per cent for the Retail Prices Index (RPI).

For the time being, the real economy seems to be coping with the rising prices, and wage growth continues to outstrip CPI. The balancing act will continue to become more challenging and with the barrage of uncertainty, it feels as if a policy mistake, for example raising interest rates too quickly or not quickly enough, becomes increasingly likely.

Jenny Renton is an investment manager at Ruffer

This article is sponsored by Ruffer

Ruffer LLP is a limited liability partnership, registered in England with registered number OC305288 authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. The information contained in this article does not constitute investment advice or research and should not be used as the basis of any investment decision.