The quest for simple but fair ratios on charitable expenditure is fraught with difficulty, says Gareth Jones.

I would encourage anyone interested in charity transparency and reputation issues to take a look at the UK charity regulators' consultation on the next FRS 102 SORP.

It contains several controversial proposals, some of which seem designed to provide easily digestible metrics on controversial aspects of how charities operate.

Notably, there is the introduction of a “key facts summary”, which it is suggested might include charitable spending as a percentage of total income.

Charity register developments

These proposals echo recent amendments to the Charity Commission's online charity register, suggesting a determination to give the public metrics for judging how much is spent on “the cause”.

The story of the charity register metrics began in March 2015, when the Commission launched its work-in-progress “beta” online charity register. This gave major prominence to a percentage figure for each charity’s “charitable spending”, until the True and Fair Foundation used to it to produce a misleading report which the Commission itself called “flawed”.

To its credit, the Commission sought to rectify this, recognising that context is important. Unveiled last month, the register’s latest incarnation includes a lengthy and intelligent explanation of why such ratios can differ across different types of charity, and offers two new metrics for charitable spending.

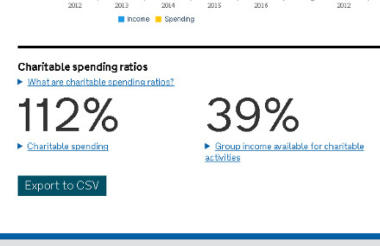

The trouble is, there is now so much context that it is hard to work out what to think. The underlying method for “charitable spending” is now “charitable spending (including governance costs) as a percentage of the group’s total income available for charitable activities”.

Meanwhile, “group income available for charitable activities” is derived from – and brace yourself for this – “the charity group’s total income adjusted for the trading subsidiaries costs of income generation and other costs to give the percentage available to the parent for charitable spending”.

It is hard to see the average journalist or member of the public taking these metrics and their context on board and adjusting their expectations of charitable expenditure accordingly. More likely is that they will just take the raw figure that best reinforces their existing beliefs and ignore the rest.

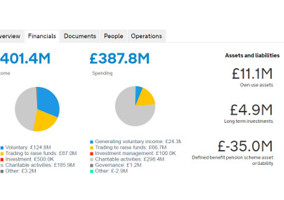

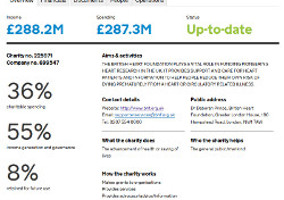

The British Heart Foundation is interesting as an example. Its extensive trading activities mean it was previously listed as having just 36 per cent spend on charitable activities.

Now, its charitable expenditure is listed as 112 per cent, and its group income available for charitable activities is 39 per cent. Quite what we are to conclude from these figures I’m not sure.

All of this indicates just how difficult it is to come up with charitable spending metrics that are sufficiently simple for people to understand, and yet sufficiently nuanced to be insightful.

Race to the bottom

There is another, bigger problem with all this. Even if such a balance can be found, it’s hard to see how encouraging a race to the bottom in terms of minimising support costs is helpful.

According to the aforementioned SORP consultation, Charity Commission research has shown that there is "considerable public interest" in charities' staff and administrative costs.

Effectively, the SORP Committee is seeking to serve a significant portion of the public which believes charities are wasteful with their donations and shouldn’t pay staff or invest in back office capacity.

Yet the public is driven by a misconception about the most effective way for charities to operate, and one that won’t be changed by simply making figures available.

Indeed, all it serves to do is further discourage charities from investing in the sorts of things that other sectors take for granted. Charities already invest much less than private sector organisations in back office functions and in pump-priming new products or initiatives.

Perhaps they would serve beneficiaries more effectively if they spent more?

Note: This article has been edited to make clear that it is the SORP Committee, not the Charity Commission, that is conducting the consultation on the future of the SORP.

Related items