It is difficult for non-investment professionals to look beyond the hysteria that often accompanies media commentary about stock markets and share prices. “Billions wiped off stock markets” is a far more lurid and exciting headline for newspapers and other media outlets than perhaps “Share prices make steady gains” or even “Billions wiped on to stock markets”. Admittedly this final headline is not one that is ever likely to grace the front page of any newspaper but it is surprising how often billions are actually added to stock values.

The bias towards the doom-laden can be seen most clearly in Google search results. A search for the exact phrase “stock market rises” returned just 65,000 results at the time of writing, whereas “stock market falls” returned 227,000 and the expression “stock market crash” returned 4.23 million. Non-market participants might be forgiven for thinking that investing in equities is a mug’s game with every crisis being the opportunity to take the fasttrack to financial ruin. Nothing could be further than the truth. Since 1900 investors in UK equities have made an average real annual return of over 5 per cent according to Triumph of the Optimists by Dimson, Marsh and Staunton, beating both bonds and cash by a comfortable margin and confounding this negative perception.

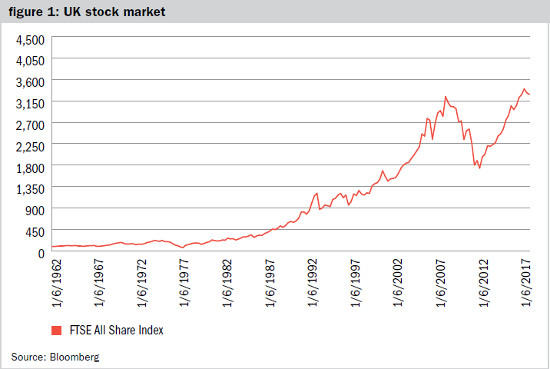

Figure 1 shows the capital only performance of the FTSE All Share Index, the broadest measure of stock market prices, over the last 56 years since 1962 when the index was created.

It is obvious that, even upon a cursory glance, the long-term trend in share prices is up and this is despite there being a stream of crises to unsettle markets throughout that period including, but not limited to, the Vietnam War, Watergate, the oil price shock, the secondary banking crisis, the three-day week, the miners’ strike, the Falklands war, black Monday (the 1987 stock market crash), the Iraq war, the 1990s recession, black Wednesday (the ejection of the pound from the European ERM), the Latin American debt crisis, the LTCM blowout, the bursting of the dotcom bubble, 9/11, the second Iraq war, the financial crisis, the Euro crisis, two hung parliaments and Brexit.

Despite all that the UK stock market is still over 40 times the level it started at back in the early sixties – and that is without re-invested income. This long-term growth of share prices is despite the accompaniment of regular incidents of doom and despair and is a testament to the long-term, positive return characteristics of equities as an asset class.

Positive returns

It is worth spending some time explain why equities actually offer positive returns over the long term. According to Bloomberg the current constituents of the FTSE All Share Index are making around £200bn of annual after-tax profits. From these after-tax profits companies make payments to their shareholders both as ordinary (ie ongoing) and special dividends. In 2018 total ordinary dividends from this group of companies to shareholders were expected to be approximately £100bn in round numbers with perhaps a further £5bn of special payments on top. This gives shareholders the first component of their equity return – income in the form of dividends.

The £100bn to be paid roughly equates to a dividend yield of 4 per cent at the time of writing and is comparable in some respects to the interest paid on cash deposits and bonds and the rental income from property. However, profits and dividends are not fixed and tend to grow over time, which drives share prices higher.

Profit and dividend growth for equities comes from two sources. Firstly, companies tend to capture inflation in their profits and this feeds through to dividends, although it should be noted that the link is not perfect. This happens because positive price inflation means that the prices of the goods and services that companies supply are rising and this increases their revenues. Provided companies are able to control their costs sufficiently well this will feed through to increased profits and, in turn, to rising dividends. This is not the case for most bonds, which generally have fixed interest payments and hence bonds are not good investments in periods of high inflation.

Property rents also tend to rise with inflation but, again, the link is not perfect. Many lease contracts have upwards-only rent reviews and many have a degree of inflation linking but this is not always the case. Interestingly, cash deposit interest rates tend to rise with inflation (usually as central banks put up rates to combat inflation) but will eventually subside once inflation starts to fall, so returns fall back. This is not the case for equities, where inflation gets baked-in as goods and services prices rarely fall (ie inflation turns negative). In fact, since the retail price index (RPI) was created in the late 1940s inflation has been negative in just three separate periods, cumulatively totalling only a year of falling prices in over 70 years of observations.

The CPI rate of inflation which superseded the RPI has only been negative in three months in the last 30 years. This partly explains why equities are a positive nominal return (ie. before inflation is accounted for) asset class but not why they are a positive real return (ie. after inflation is accounted for) one.

Retained earnings

The second element of growth for equities comes from retained earnings. As noted earlier, UK quoted corporates distribute around £100bn of their £200bn of after-tax profits, leaving £100bn to be invested by the companies to expand. The money is used in myriad ways including new factories, shops and other premises, investing in intangible assets such as pharmaceutical R&D or software, boosting working capital to be able to supply more customers, funding restructuring programmes to cut costs or buying up other companies to gain synergies and strategic advantage. If all the £100bn were to be invested in fixed assets (this is not usually the case), UK quoted corporates would grow their combined asset base and, hence, their capacity to produce goods and services by around 7 per cent. This is the fundamental reason that equities deliver positive long-term real returns; they are able to grow their revenues, profits and dividends ahead of inflation through the retention of non-distributed profits, a factor that is not applicable to cash, bonds or property.

However, and unfortunately, it is also obvious to even a casual observer of figure 1 above that stock markets experience periods of negative returns. Share prices fall for many reasons; falling profits, growing recessionary expectations, political uncertainty and rising interest rates are just four commonly cited causes. Nonetheless, there are actions that investors can take to mitigate the risk of not achieving a decent return.

Long-term view

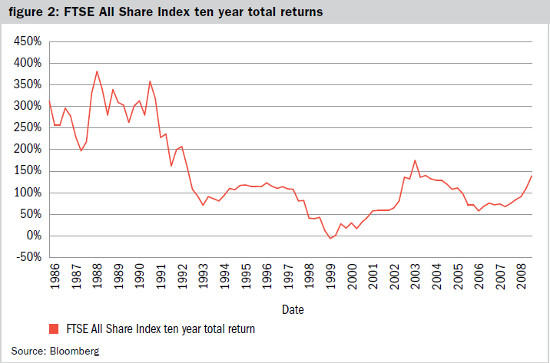

The first and most important of these is to take a long-term view. Generally speaking, the longer your investment time-scale the less likely you are to lose money in equities. Figure 2 shows the total returns generated by investing in the UK stock market for ten-year periods since the mid-1980s.

This shows that when taking a ten-year view it has been extremely difficult to lose money in equities. Only in one short period was it possible to make a loss. The unfortunate investor would have had to have decided to take the plunge into equities towards the top of the dotcom bubble at the end of 1999 and then panicked out at the very bottom of the financial crisis ten years later and even then would have only recorded a small total return loss.

The chart also shows the importance of investing after market falls. For example, if an investor had bought the market just prior to black Monday in 1987 they would still have made a respectable 180 per cent total return over the subsequent decade. However, this return rises to 340 per cent if the investment had been made just weeks later after the stock market crash. Unfortunately, it often takes nerves of steel to take advantage of such opportunities given the media’s predilection for sensationalising market setbacks.

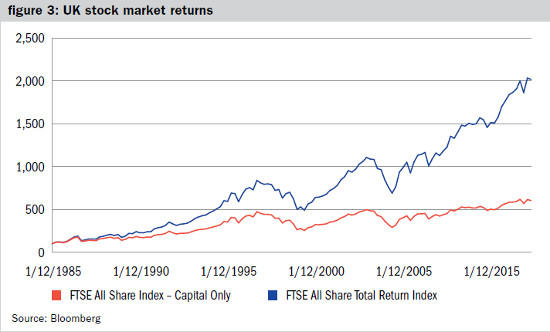

Investors can also mitigate their risks by focusing on dividend income. Income is a vitally important part of total return as figure 3 illustrates.

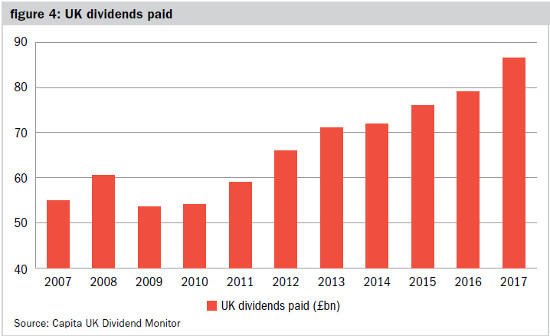

There is also plenty of statistical evidence to suggest that income-focused investment strategies can generate attractive long-term returns but there is another important reason for concentrating on income. Dividend payments are a far less volatile component of return than the capital element, as figure 4 demonstrates.

Total dividends paid have only fallen once in the last decade and then only by 10 per cent during the worst year of the financial crisis. Since then dividends have been on a steady upwards trend with no down years – unlike the stock market. Dividends are likely to have risen by around 20 per cent since the EU referendum, having been given a turbo boost by the devaluation of the pound since then and illustrating that not all crises are necessarily bad news for equity investors. Furthermore, we are presently living through an unusual period with investing conditions not seen since the early 1960s whereby shares yield more than cash and investment grade bonds. This means that investors can boost their immediate income by investing in equities and improve their expected long-term returns.

Investors should of course seek to diversify their holdings and not have all their eggs in one basket. However, there are a number of important caveats to this sensible advice. Firstly, most of the diversification benefits of having a high number of stock investments is achieved by owning just 40 stocks, although it should also be stressed these 40 should not all be in the same industry.

Secondly, wide diversification will almost inevitably mean exposure to underperforming assets; many investors may currently be wondering why they diversified into emerging markets in recent years on the pretext of reducing risk.

Lastly, while it is true to say that diversification reduces risk in normal market conditions this was not the case during the financial crisis when many asset classes that were supposed to be uncorrelated all recorded extreme negative returns at the same time.

In conclusion, would-be investors should always remember that companies have the financial characteristics that enable them to generate attractive real returns for their shareholders over the long term. They should do their best to ignore the media hysteria that often accompanies stock market falls and also remember that such falls have almost always been the best time to buy shares. Investors that have taken a long-term view and remembered the importance of income have been handsomely rewarded by investing in the UK stock market.

Patrick Harrington is investment director at OLIM

Charity Finance wishes to thank OLIM for its support with this article

Articles contained on this website do not constitute investment advice or research and should not be used as the basis of any investment decision.