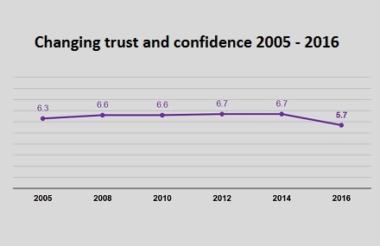

Last week, the Charity Commission produced an extensive report showing that public trust in the charity sector has never been lower – at least, not since anyone started measuring it. Large charities were particularly distrusted.

It’s a wake-up call for a sector which is supposed to be there for the good of the people. Because a very large section of the population don’t seem to think charities are doing much good.

The people of England and Wales trust charities – especially large charities – less than they trust the average man on the street.

It is no use blaming the media for that, either. Yes, there have been negative stories, but the public don’t distrust charities just because they have been told to by the Daily Mail. Many people distrust charities because they see them as part of a wider problem. The media just confirmed what people already thought.

The UK public are fresh from eight years of financial pain, caused by wealthy speculators in New York and London who mostly don’t appear to have suffered at all. They are fed up with an unaccountable elite who don’t share their own experiences, and they think that includes a hundred or so London-based charities with incomes of more than £100m a year.

These charities – even those which exist to combat poverty and inequality – are viewed by a significant number of people as a fat, comfortable sinecure for white collar workers in the London club, who pay themselves nice big salaries at the expense of people who make a living trekking up and down the endless aisles of an Amazon warehouse, being penalised if they stop to go to the loo.

This is obviously a generalisation. The view of charities in the UK is far more nuanced than this, and there’s still a lot of love for the sector among the British public. Otherwise charities wouldn’t have received billions of pounds of donations last year. But this idea that big charities are fat and selfish is a growing and powerful theme - even elsewhere in the sector itself.

The problem is that large charities have done too little to disabuse the public of this view. First, it is unfortunately the case that the senior staff in these organisations are part of the London bubble. A third of all charitable income accrues to bodies based in just seven London boroughs, clustered around the Houses of Parliament. That doesn’t look good.

Even Charity Commission board member Claire Dove seems to share this perception. Dove, the chief executive of Liverpool homelessness charity Blackburne House, was speaking at the launch of the Commission research into trust, and she went out of her way to talk about how unrepresentative the people in the room were.

The pressures which have caused people to lose trust in charities are exactly the same pressures which drove the same people to vote to leave the EU.

This seems to have been a decision driven by a sense of disenfranchisement and anger and frustration, among people who have not shared in the prosperity the EU is supposed to bring.

The people who took that decision were largely the people charities are supposed to serve – the elderly, the unemployed, those disadvantaged by poor education. And they were also part of charities’ natural supporter base – the regular givers who put their hands in their pockets and give a small regular donation.

The less well-off have always been disproportionate givers to charities. In absolute terms the rich give more, but people on lower wages give a higher percentage of their income.

It’s evident from the events of the last week that charities don’t speak with the same voice as those people. Charity workers almost universally voted to remain, and their organisations universally supported that cause. Too many of their donors and beneficiaries did not.

This is a real problem for charities, because the sector exist to make life better for disadvantaged people, and if charities can’t speak on behalf of those people, what are they good for?

In fact, you could argue that charities hardly speak with any voice at all. For one reason or another, charities have hardly spoken out at all in the great national debates of recent years – over austerity, and who will govern us.

Charities are of course limited by the exigencies of survival and the requirements of law to focus only on their own cause, and are perhaps also dissuaded by the Tory party’s ideological opposition to campaigning.

But for whatever reason, it feels as if too many charities have become bit-part players, focused only on their own little corner of the world – dogs, or prostates, or cycling in Bermondsey, or whatever it may be – without a wider social conscience.

It’s asking a lot of charities to engage in this way, and it’s not realistic for many which are simply struggling to keep going, but it is an important ambition. Too many bodies have focused on one aspect of their beneficiaries’ lives, without thinking that the problems they face are part of a systemic disadvantage.

And to conquer disadvantage, the whole frame of the national debate has to change. Disease and poverty and inequality aren’t conquered without a framework for fairness.

Instead in many organisations – certainly not all, but many – we’ve seen a fixation on funding and growth, which has driven large charities to focus on commissioning and contracting, and on pestering donors in ever-more-novel ways to fill out a direct debit form, until those donors finally lost patience and gave voice to their frustrations in the Daily Mail.

The way charities responded to criticism has been instructive, too. Because, broadly, the answer has been silence and sullen resentment.

This silence appeared initially to be a PR strategy – just ignore the problems and they’ll go away – which frankly hasn’t worked. But in the end it’s deeper than that – deeper than a failure on the part of big charities to defend their central London offices and six-figure CEO salaries. It’s about the sector’s failure to defend its own beneficiaries and connect with its donors – to frame the debate, or even take part in it.

I’m struck here by the example of the Trussell Trust, which has notably failed to be silent. Instead it’s been vocal about the fact that it shouldn’t need to exist. It has taken seriously the age-old adage that a charity should fight to be able to shut down, and lobbied continuously for a better life for disadvantaged people. It has done so publicly and conspicuously.

Too many others, it appears, have been absent from the conversation. Perhaps I’ve just tuned them out, or the pervasive stream of media nonsense has drowned them out, but few others seem to be lobbying in the same way. I wonder if too many have decided the best way to get things done is to play the game – to engage in behind-the-scenes white-collar Whitehall wonkery – which has meant that they no longer speak about what they really feel.

Because it’s not enough to get results. You have to be heard getting results. If the people feel disenfranchised, they should feel that charities are acting as their voice, not as part of the problem.

This piece of writing probably appears very critical, but if so, it’s not because I don’t believe in the value of the charity sector. I do, or I would not have spent most of the last decade writing about it.

I believe that the charity sector is one of the best and noblest parts of our society. But even more than I previously realised, Big Charity has a hell of a communications job on its hands.

Previously I’ve advocated that sector bodies need to reach out and speak to their supporters. But now it appears to be more than that.

Charities need to reach out and speak for them, too.