With each new Brexit development, planning for the future and knowing how to manage your charity’s finances through all the uncertainty hasn’t been getting any easier. To help our clients as best we can, we’ve tried to shed a little light on what the future may hold.

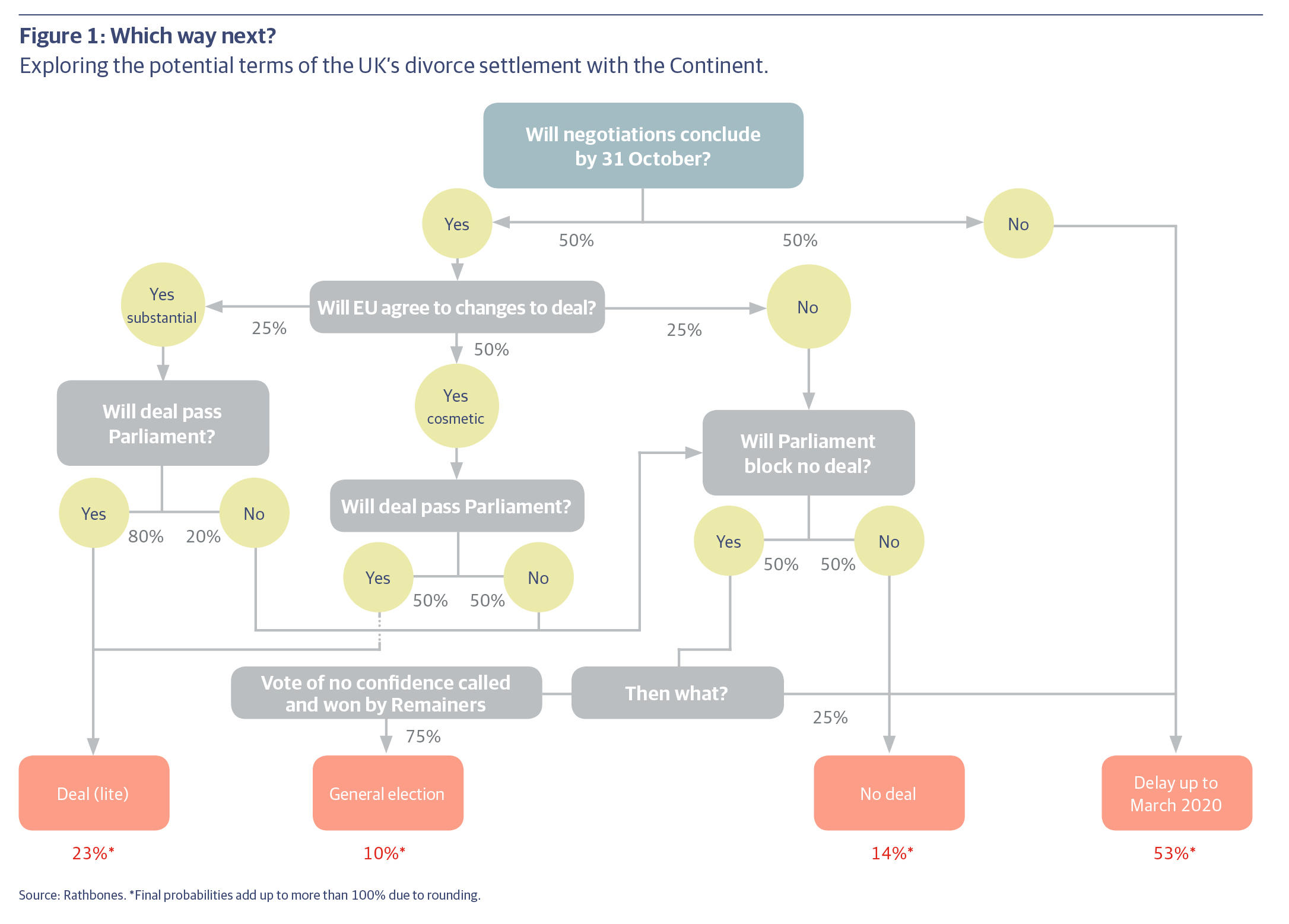

We’ve been keeping track of the various possible Brexit outcomes with our Brexit decision tree since last December and we’ve updated the likelihood of each outcome, taking into account our new Prime Minister, Boris Johnson. Brexit has brought him there, and Brexit will dominate his agenda for his first three months in office. Kicking the can down the road has been our most likely scenario since we first published the decision tree in December last year, and we think Mr Johnson’s election keeps it there for the foreseeable future.

Of course, there are still many unknowns. Yet resigning ourselves to a shrug of the shoulders would mean we’re not thinking hard enough. Stopping at “we don’t know” today could make us slow to react tomorrow if the situation becomes clearer. And it’s a missed opportunity. That little extra knowledge – that some outcomes are more likely than others – is important for investors, because financial markets are nothing if not probability-weighting mechanisms.

The road to Halloween

Mr Johnson takes on many of the same challenges faced previously by Mrs May. He will have to contend with a dwindling government majority, making it very difficult to get Parliament to stand by and allow his threat of a ‘no deal’ – “do or die” – Brexit to come to pass. April’s Cooper-Letwin Bill, whereby Parliament took control of Commons business, has set a profound precedent and its implications are likely to be repeated if leaving the EU without a deal – the default option – looks increasingly likely as the 31 October deadline approaches. To be sure, it is not off the table. But as we work through our decision tree, it becomes clear that ‘no deal’ as early as October is not as likely as some commentators contend (Although the probability of ‘no deal’ ultimately occurring is significantly higher). Mr Johnson has said that leaving without a deal is not his preferred option and that it has a million-to-one chance of occurring, which makes it clear that the embrace of ‘no deal’ is a negotiating tactic.

We think it is unlikely that the EU will agree to any more substantive changes. That said, our recent research trip to Brussels revealed a willingness from the EU Council to grant an extension of the current deadline to March 2020. Its president-elect, Charles Michel, is a little more amenable to the idea of a hard Brexit than some of his colleagues, but he doesn’t take office until December, and the incumbent president, Donald Tusk, would likely grant an extension in our opinion. Our decision tree puts the probability of extension at 53 per cent.

Mr Johnson has said that the UK will definitely leave on 31 October but there is very little time for him to resolve Brexit as it stands. The leadership contest finished just before Parliament’s summer recess, which lasts until early September. The new government will therefore have just seven weeks before the October deadline once it reconvenes.

It is possible that the most staunchly pro-Brexit MPs will call a vote of no confidence if he doesn’t deliver, but we think this risk is negligible. Conversely, a vote of no confidence could also occur if ‘no deal’ is looking likely, potentially leading to a general election. Parliamentary rules on timing mean that a vote of no confidence must be tabled before 9 September – the fifth working day after Parliament returns from the summer recess – if a new government is to be established before 31 October. This also seems unlikely.

The economic backdrop

If the economy weakens as a result of Brexit, this could of course have knock-on effects for charitable donations, so it’s important for charities to consider this bigger picture. Since the referendum, the UK economy has grown at an historically weak rate – weak, also, by international comparison. Business investment has been particularly hard hit: higher outward investment has been accompanied by lower investment into the UK from the EU, amounting to an estimated £11.8 billion of lost foreign direct investment.

The Bank of England’s investment intentions survey indicates a contraction of business investment for the first time since the immediate aftermath of the referendum. This is consistent with a swathe of leading indicators of broader economic activity that point to extremely weak growth or contraction. The economy’s fate rests on household behaviour. Of course, the rest of the world is also undergoing something of a slowdown, but the UK looks weaker than most Western economies.

For investors, including charities, a crucial point is that Brexit is not a globally systemic event and non-UK markets are unlikely to move much in response. We believe that financial markets are pricing in a much higher chance of a ‘no-deal’ Brexit than our decision tree suggests. On a long-run basis sterling appears very undervalued, even in a highly adverse scenario for the UK economy. So exposing portfolios to considerable currency risk by overweighting overseas assets may not be the best strategy, as returns from those assets would be eroded if sterling were to appreciate. Brexit uncertainty will continue to bring volatility for UK investors. But “we don’t know” doesn’t lead us to “sell the UK”.

Andrew Pitt is head of charities at Rathbone Investment Management. For further information please visit Rathbones’ Brexit Hub.

This content has been supplied by a commercial partner. Rathbone Investment Management is the overall partner for the Charity Awards.

Related articles