The ten-year investment returns from 1,500 charity portfolios are analysed by Graham Harrison.

Arthur Conan Doyle’s famous detective, Sherlock Holmes, was known to state: “It is a capital mistake to theorise before one has data. Insensibly one begins to twist facts to suit theories, instead of theories to suit facts.”

Well, thanks to the willingness of participating investment managers to provide transparency on the performance of the charity portfolios they manage, the ARC Charity Indices are now celebrating having accumulated a decade of data.

I’m sure that Sherlock Holmes would have welcomed the availability of these cold, objective facts for use by all charity investors who are seeking to place portfolio performance into a peer group context.

Strength in depth

The ARC Charity Indices are constructed on the basis of around 1,500 underlying discretionary portfolios submitted by 30 investment managers. We produce four sets of charity indices, divided into four ‘risk’ categories, based on volatility.

The central concept behind the design of the ARC suite of indices is the notion that investors are interested in outputs rather than inputs. Thus, there are no pre-set asset allocations; no asset class restrictions; no concentration limits; and no index performances used.

Such rules are concerned with inputs. Rather, it is the output that determines the classification and ranking of each portfolio. The risk of each portfolio is compared to the risk of equity markets. Then the performances of portfolios that have evidenced similar risk characteristics are compared.

Why classify portfolios according to their performance pattern rather than, say, their asset allocation? The answer, in our view, is clear: consumers of the investment management industry’s services are primarily interested in outputs not inputs.

To draw an analogy, most car owners select a car on the basis of the functions it is expected to perform rather than the components used in its manufacture. A car is chosen based on its expected usage: the school run, driving to work, family holidays, etc.

The same principle applies to the selection of a discretionary portfolio manager by a charity investor. The probability of achieving the investment objective is more important to the charity investor than the way in which it is achieved.

Dividing portfolios into four risk categories – which we have termed ‘equity risk’, ‘steady growth’, ‘balanced asset’ and ‘cautious’ – allows portfolios with different components, but similar objectives, to be compared.

Portfolio distribution

Over the last decade, financial markets have followed a rollercoaster ride. Equity markets rose strongly (up around 50 per cent) from 2003 to 2007. The financial crisis in 2008 saw world equity markets lose all these gains. Then, from early 2009 to the end of 2013, equity markets again rose strongly (roughly doubling).

The return path has been bumpy for most investors and has tested their resolve and risk appetite. Some investors undoubtedly went into 2008 with portfolios that were too heavily invested in risk assets, then lost their nerve and cashed out at the bottom. That is a cardinal sin.

Many of these investors have only recently reinvested their capital in the equity markets, or are still waiting on the sidelines before recommitting capital to the markets and no doubt rueing the opportunity lost. A few investors, through luck or judgement, had reduced risk prior to 2008 and were brave enough to recommit to financial markets early in 2009. Such investors are now sitting pretty, though they are in the minority.

Key trends

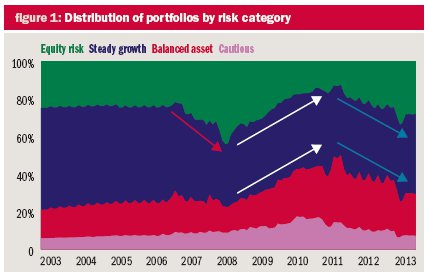

The evidence for these trends is set out in figure 1, which shows the distribution of the ARC universe of portfolios (for both charities and private clients), split between the four ARC risk categories over time.

The chart reveals four phases over the last decade.

- During the relatively benign bull market from 2003 to 2006, the risk profile of portfolios covered by the ARC indices was relatively stable.

- In 2008, while the proportion of lower-risk portfolios remained stable, the red arrow indicates there was a sharp increase in the number of portfolios classified as ‘equity risk’, driven by the failure of alternative asset classes to provide the diversification benefits they had delivered in the last bear market.

- In 2009 and 2010, many charity portfolios de-risked, as shown by the parallel white arrows, as investment managers and their clients sought to come to terms with the implications of the financial crisis.

- From 2011 onwards, the effect of negative real interest rates drove many charity investors to increase their equity weightings, as shown by the parallel blue arrows.

Thus, a decade later, the distribution of portfolios in the ARC indices between the four risk categories is roughly where it started. The path suggests that charity investors have not learned the lessons of the past, and will still tend to reduce portfolio risk after experiencing losses, and increase portfolio risk after a period of equity market buoyancy.

Hopefully, the greater emphasis on risk and suitability in recent times will avoid history repeating itself.

Ten-year performance

For those charity investors which have been invested over the whole of the last ten years since 2003, returns have been reasonably buoyant.

Figure 2 sets out some performance data organised by each of our risk categories.

Figure 2: Ten-year performance data | ||||

ARC Charity Index | 10-year return % | Maximum drawdown % | Annualised return % | Annualised volatility |

Cautious | 65.4 | (5.7) | 5.2 | 3.4 |

Balanced asset | 82.8 | (18.2) | 6.2 | 6.7 |

Steady growth | 96.2 | (27.1) | 7.0 | 9.2 |

Equity risk | 105.6 | (34.4) | 7.5 | 11.7 |

The message from figure 2 is that the financial markets have rewarded investors for taking risk. However, the maximum drawdown figures show clearly the extent of ‘pain’ that needs to be borne during difficult market conditions.

By ‘drawdown’ we mean the longest period of cumulative loss, which in the last ten years was during 2008. If an investor went into the market at exactly the wrong time they would, for instance, have experienced a loss of 27.1 per cent in a ‘steady growth’ portfolio. Thus ‘drawdown’ gives an idea of the worst case scenario for a given risk profile over the period.

Annualised volatility is a commonly-used risk measure that shows the variability of returns from the mean. Simply put, once in every six years you would expect a loss in excess of 11.7 per cent in an equity risk portfolio, and you would expect a similar gain.

Looking back over the last decade of performance data, there is strong evidence that charity portfolios have tended to adapt their risk profiles in reaction to financial market conditions, to their detriment. Acting on prevailing market sentiment appears to have caused relative value destruction.

If the next ten years deliver similar annualised total returns, charity investors should be content.

The path will inevitably be bumpy but so long as performance relative to peer group remains reasonable, mandate changes are probably best avoided.

As Sherlock Holmes might have deduced, the evidence strongly suggests that adjusting investment policy to fit in with the prevailing investment zeitgeist is “a capital mistake”.

Graham Harrison is group managing director of Asset Risk Consultants.