The Woodland Trust is the top performing charity in this month’s review, reporting a 33 per cent increase in income to £49.4m. It is one of 59 members of the haysmacintyre / Charity Finance 250 Index which have year ends falling in October, November and December of 2016.

The environmental charity benefited from a £9.1m legacy, which helped boost overall legacy income by 54 per cent to £21.9m. The charity also received £2.3m from the People’s Postcode Lottery, which contributed to a 51 per cent increase in voluntary income to £10.6m. The trustees concede that growth in other sources of income was much lower at 8.6 per cent, and that the growth generated by exceptional income in 2016 is unlikely to be repeated in 2017.

Legacy income is, of course, a mainstay of many animal welfare charities, and this year is no exception. Legacy income has gone up by 23 per cent to £14.9m at Battersea Dogs’ and Cats’ Home, where it accounts for 36 per cent of total income, and by 10 per cent to £24.8m at the Donkey Sanctuary, where it accounts for 65 per cent of total income.

Similarly, it has gone up by 6 per cent to £18.5m at Blue Cross, where it accounts for 52 per cent of total income, and by 71 per cent to £7.8m at World Animal Protection, where it accounts for 23 per cent of total income. Cats Protection is the only animal charity to buck the upward trend, with legacy income falling by 14 per cent to £26.1m, though this income stream still accounts for a significant 47 per cent of its total turnover.

It is not just animal charities, however, that are benefiting from a surge in legacy income. Health-related charities including Sightsavers International, MS Society and Médecins Sans Frontières (UK) all report annual growth rates in legacy income of 20 per cent or more.

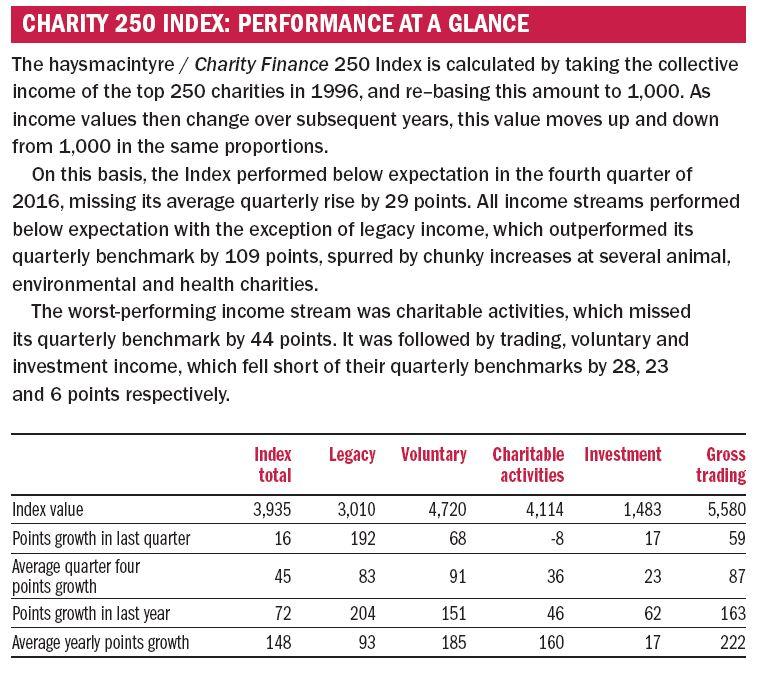

While two-thirds of the charities in the Charity 250 Index which report results in the fourth quarter have boasted income rises, there are some chunky falls in income that have helped depress the overall growth of the index.

The Aga Khan Foundation (UK), for example, reports a 62 per cent fall in income to £27.9m, driven by an 87 per cent fall in funding for “institutional development” from £57.1m to £7.2m. The bulk of institutional funding in 2015 was used to finance a student housing development in the King’s Cross area of London, which opened in January 2016. The majority of rooms are used by students attending programmes at The Institute of Ismaili Studies and The Aga Khan University Institute for the Study of Muslim Civilisations.

There was also a big fall at the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (Great Britain), where total income was down 46 per cent to £39.1m. This was due to a 91 per cent decrease in grant income from the Mormon charity’s Utah-based parent company, the Corporation of the Presiding Bishop of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, from £36.8m to £3.2m. The British arm acts as the agent of the parent company in the transfer of funds to and from other Church entities globally.

Religious charities

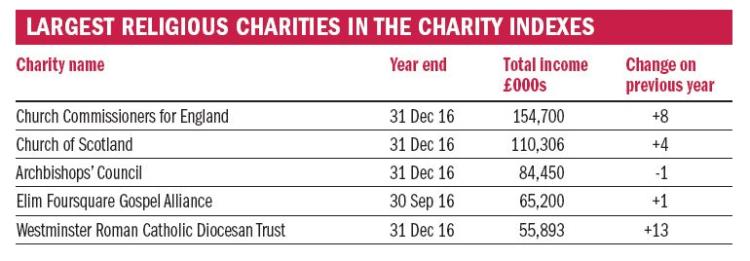

Across the Charity 100 and Charity 250 Indexes, there are 22 religious charities, ranging from the Church Commissioners for England with annual income of £154.7m to the Chelmsford Diocesan Board of Finance with £23.5m. In terms of sector, they span many of the different denominations of Christianity, such as the Church of England, Roman Catholicism, Methodism and Mormonism. Judaism is also represented, via United Synagogue.

The representation of religious charities in the Indexes has decreased over the last year, with four diocesan charities not keeping pace with the three-year average income requirement of £21.2m for membership of the Charity 250 Index. At first glance, this may seem like a performance issue, though this is not always the case.

One of last year’s exits, the Diocese of Hexham and Newcastle, for example, saw its annual income fall from £22.2m in 2014/15 to £12.2m in 2015/16. This resulted from the board’s decision to no longer consolidate the accounts of its former social welfare subsidiary, St Cuthbert’s Care, into its own accounts, following changes to the latter’s governance. St Cuthbert’s Care is now an independent charity with annual income of £9.5m at 31 March 2016.

A similar restructuring resulted in the relegation of the Congregation of the Daughters of the Cross of Liege to the Charity 250 Index earlier this year, when its three-year average income fell below the £58.2m requirement for membership of the Charity 100 Index. Total income at the religious charity fell from £65.4m in 2013/14 to £47.8m in 2014/15 and £36.1m in 2015/16, reflecting the sale of St Anthony’s Hospital to Spire Healthcare in May 2014. While the headline figures show a fall in income, income from the charity’s continuing operations actually increased in 2015/16 by 2 per cent.

“It is becoming increasingly common for religious orders or diocesan charities that have set up hospitals, care homes or schools to sell them or hive them off as independent charities, so that they can be managed with the requisite level of focus and expertise,” comments haysmacintyre’s head of faith charities Adam Halsey. “They may continue to support the charity but it is more likely to be as a grant-making trust, rather than as a direct service provider.”

While some of the big income falls are of this type, many are still facing challenging times financially.

The primary source of income for most diocesan boards of finance is the contribution from the parishes in their jurisdiction – known as the “parish share” – which in turn is raised from collections, committed giving and Gift Aid from local congregations. The dioceses are responsible for paying for the clergy and other diocesan ministries that support the parishes.

Aggregate figures published this year by the Church of England show that planned giving, which accounts for around a third of parish income, increased by 19 per cent between 2007 and 2015 to £338m but in real terms decreased by 5 per cent. Over the same period, the number of donors decreased by 14 per cent to 542,600.

As for collections, the figures indicate that this income stream performed even worse. It fell from £58.3m to £57.2m, which translates to a real terms drop of 22 per cent. The report suggests that “people are either choosing to give in a more planned way or perhaps visiting church less frequently”.

The biggest threat to the dioceses’ main source of income is, of course, diminishing congregations. These can result from secular trends in society, questions over the church’s relevance, reputational issues and competition from other faiths and denominations.

“In the face of static or falling income, diocesan charities are looking much more creatively at how they can deploy limited resources effectively across the parishes to maximise community engagement,” says Halsey. “The use of newly qualified curates, for example, to support the clergy is proving to be an efficient way of maintaining coverage levels across the parishes.