The Charity Commission has come in for criticism over the behaviour of its board and its governance structure. Kirsty Weakley takes a closer look at just who is running the regulator.

Earlier this month Sir Stuart Etherington, chief executive of NCVO, wrote to Rob Wilson, minister for civil society, telling him that the governance of the Charity Commission needed to be looked into “as a matter of urgency”. The week before, chief executives body Acevo also expressed dissatisfaction with the board, and called specifically for an inquiry into the conduct of one of the board members.

These sentiments, from the two most significant infrastructure bodies for the charity sector, appear to be the tip of a much larger iceberg. A number of other infrastructure bodies have also publicly questioned the role of the board - one said the regulator was "losing the trust of those they regulate". Former staff and board members at the regulator, as well as sector legal advisers, have all privately expressed concerns to Civil Society News.

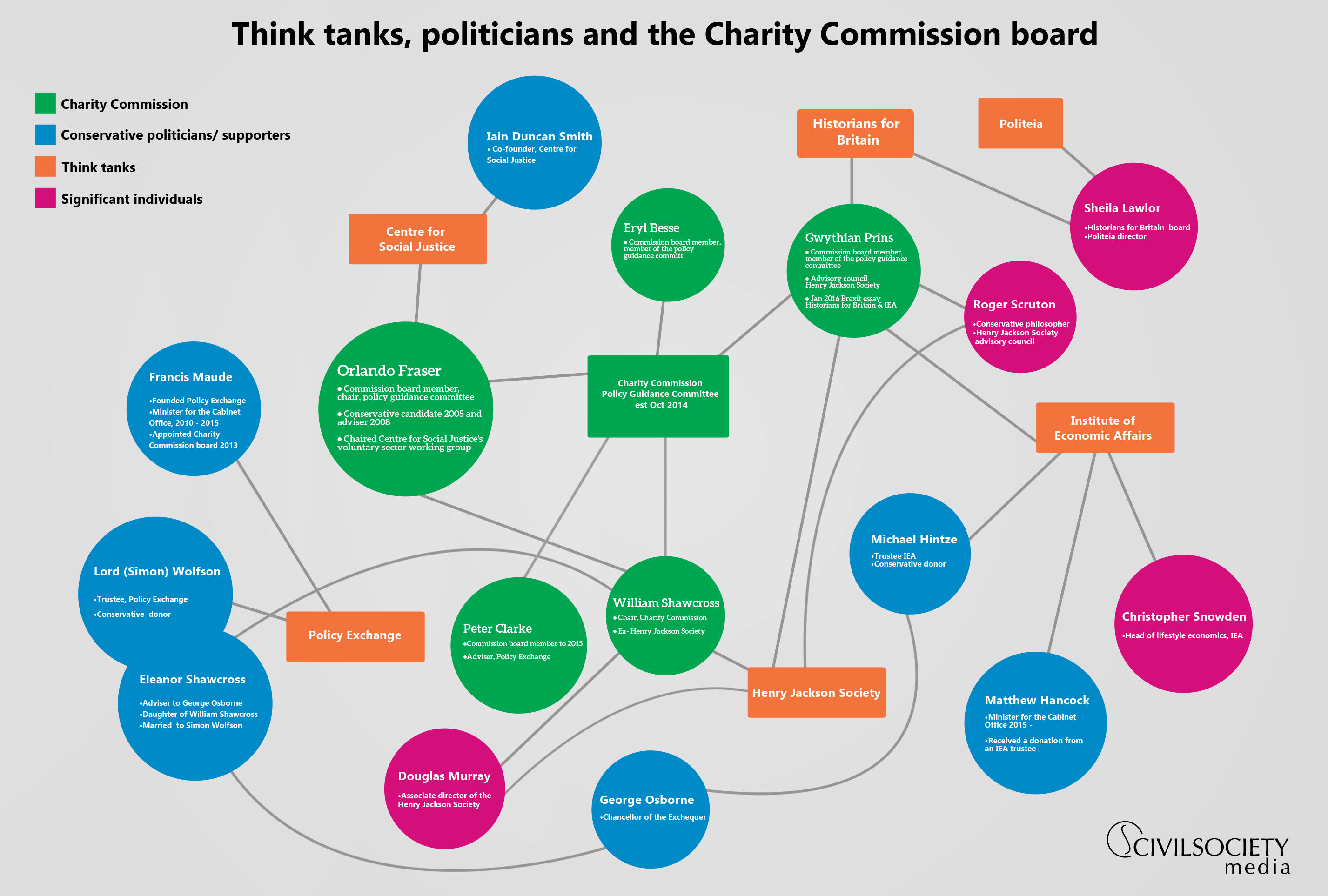

There are concerns that a clique at the heart of the board has a strong political and ideological stance, with several members having close links to Conservative politicians and right-wing think tanks, and that this has led to a hardline approach to sector policy.

These bodies are worried at the level of power being gathered by this group, and their continued involvement in the day-to-day running of the regulator.

So what has caused so much concern? Is it justified? And what should be done about it?

What is the source of the concerns?

There has been a long-standing problem with the perception that the Commission’s board is a reflection of the government of the day. When William Shawcross, the current chair, was first appointed, it did not take long for people to suggest that it was a politically motivated decision. The previous chair, Dame Suzi Leather, was similarly accused of being too close to the Labour government.

To a great extent, this potential politicisation of the Commission board is why NCVO produced a policy paper last year calling for reform of the appointments process.

So to what extent does the current composition of the board support the calls for reform?

Three years ago when William Shawcross and Francis Maude picked an entirely new board for the Charity Commission there was a lot of emphasis on how this new board had the right skills to modernise the regulator and tackle the issues facing the sector – the implication being that the previous board did not.

But several criticisms can potentially be levelled at the new board – including that most of its members have little background in the charity sector. It is comprised of three lawyers (none who claim to have experience of charity law), two writers, one accountant and a social entrepreneur. Only the last, Claire Dove, has any significant sector knowledge.

It is also clear that the board lacks diversity and appears to be drawn from a narrow, privileged social group, which does not reflect either the voluntary sector or wider society.

Perhaps most worryingly, given NCVO’s concerns about neutrality, is also possible to draw a number of strong connections between board members, Conservative-leaning think tanks, and right-wing politicians. Taken together, these links paint a worrying picture of a regulator whose independence from government could be called into question.

William Shawcross

Until his appointment as the chair of the Commission, Shawcross was on the advisory council of the Henry Jackson Society (HJS), a right-wing charitable think tank with a focus on security and defence issues.

When he was promoting his book, Justice and the Enemy: Nuremberg, 9/11, and the Trial of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, Shawcross gave a lecture at the HJS where he praised it for its strong stance on the “threat of Islamist terrorism throughout the world but also in this country”. This is just one of many examples of the public position on global threats Shawcross took prior to be being appointed to the regulator.

Shawcross has always insisted that he is not affiliated to a political party, but his stances on politically sensitive issues such as the Iraq war, Guantanamo Bay and Israel leave little doubt as to where he stands on the political spectrum. His daughter Eleanor Wolfson has been an adviser to George Osborne since 2008. She is married to Lord Wolfson, a Conservative Party donor who is a trustee of Policy Exchange, a think tank that was founded by former Conservative minister Francis Maude. Maude, as minister for the Cabinet Office in the last Parliament, appointed Shawcross, and together they appointed all other board members.

Gwythian Prins

Earlier this year Prins wrote a politically-charged essay for Historians for Britain, part of the Brexit campaign group Business for Britain. Sheila Lawlor, director of another right-wing think tank, Politeia, is on the board of Historians for Britain.

Prins’ essay has also been published by the Institute of Economic Affairs, yet another right-wing think tank which launched the “sock puppet” movement to lobby against charitable campaigning (see below). Following the outcry from Acevo and former Commission board member Andrew Purkis, the Commission said it is taking seriously allegations that Prins may have breached the Cabinet Office’s code of conduct for board members of public bodies, and that it will work with the Cabinet Office to establish if any rules have been broken.

Prins also sits on the advisory council of the Henry Jackson Society and is a visiting lecturer on security issues for the private higher education institute the University of Buckingham.

The conservative philosopher Roger Scuton credits Prins with influencing a piece he wrote for ConservativeHome in 2014, What do Conservatives believe?, which criticises “sock puppet” charities for “distorting the long-established charitable instinct of our citizens”.

Prins was also the first person to say he believed that charities should “stick to their knitting” – a phrase reused by then-charities minister Brooks Newmark to widespread condemnation.

Orlando Fraser

Fraser is the board member with the starkest connections to the Conservative Party. He stood as a candidate in 2005 and later acted as an adviser to the Conservative Party on voluntary sector issues, which was declared when he was appointed to the board. He was a founding fellow of the Centre for Social Justice, which was set up by Conservative MP Iain Duncan Smith. Fraser chaired its voluntary sector working group for the report Breakthrough Britain.

Peter Clarke

Clarke, a retired Metropolitan Police officer, stepped down from the Commission in November last year to take up the role of chief inspector of prisons. He is a trustee of Crimestoppers and is on Policy Exchange’s advisory council.

Tony Leifer

Leifer is a member of the Board of Deputies of British Jews and chair of the Jewish Council for Racial Equality. He is also a trustee of a small charity, Yad Arts.

Eryl Besse

Besse is a corporate lawyer and the Commission’s Welsh representative. Her Commission biography says she has “experience in a number of civil society organisations”. She is a member of the development committee at Magdalen College School, Oxford.

Claire Dove

Dove is chair of the umbrella body for social enterprises, Social Enterprise UK. She runs Blackburne House, which is a registered charity and social enterprise for women's education, with an income of £900,000.

Mike Ashley

Ashley is a chartered accountant and was appointed in November 2014 after Nazoo Moosa stepped down. He holds a number of other roles in the private and public sectors.

Role of think tanks

Several of the think tanks which these individuals have worked with have attempted to influence policy, particularly to reduce charities' ability to campaign.

The IEA’s director of lifestyle economics, Christopher Snowden, wrote two reports criticising charities that receive government funding and campaign. In a personal capacity its chair, Neil Record, has donated to Matthew Hancock – the man who will work with Shawcross to choose the next Commission board – on six occasions since 2010. Another IEA trustee, Michael Hintze, has also given significant sums to the Conservative Party.

Douglas Murray, associate director of the Henry Jackson Society, has been accused of making anti-Muslim statements. In October 2015 he wrote an article for the Spectator, William Shawcross is right: Islamists are skilled at lawfare, defending the Commission chair against widespread criticism.

And in 2009 Politeia published a pamphlet looking at the Charities Act 2006 which was highly critical of the Commission’s approach to campaigning.

Skills and connections

Only Dove has any experience of running a charity - and she does not sit on any of the board’s subcommittees. She also drew lower pay than any other board member, except for Fraser, who waives his remuneration, suggesting that she is less involved in day-to-day work.

Ashley and Leifer sit on just one subcommittee, Shawcross on two, while Besse, Fraser and Prins serve on three.

Nobody on the board has any experience of running a very large charity, despite the Charities Act stipulating that the board should include people with “knowledge and experience” of “the operation and regulation of charities of different sizes and descriptions”.

Several of the board – particularly Shawcross, Fraser and Prins – had a number of shared social connections and were affiliated to the same organisations, before their appointments.

This risks being seen as cronyism; at worst it could be interpreted as an attempt to install people with a specific ideology at the regulator.

There are also concerns that the board of the Commission is acquiring greater power and influence than is normal.

Policy-making at the Commission

It is normal, and indeed good governance, for boards to have subcommittees which draw on specific skills and enable a smaller group to focus on specific issues. The Commission has a number of them, all of which receive support from the regulator’s executive team, and appear to have considerable influence over the Commission’s direction.

In October 2014, the Commission quietly established a policy guidance committee. This new committee has not been announced. The first public reference to it is on page 47 of the Commission’s resource accounts for 2014/15, which were published last summer.

These reveal that the committee was “was created to ensure that our published guidance is strategically focussed in accordance with our regulatory approach and priorities”. During the year it “reviewed the schedule of work on new and revised guidance and agreed current priorities”. The committee is chaired by Fraser and its members are Besse and Prins. It is the only committee that has not sought expertise from outside the Commission through appointing an independent member.

The Commission has been curiously reluctant to explain why the committee exists. When Civil Society News requested more information about the committee’s purpose, membership, and meetings we were referred to the annual report. After submitting a request under the Freedom of Information Act we were again referred to the most recent annual report.

Since the formation of the committee there has been a noticeable increase in dissatisfaction from sector bodies and charity legal experts with the various bits of guidance issued by the Commission, culminating in the concerted and vocal condemnation of new guidance regarding charities’ campaigning on the European referendum.

The Commission came under fire from the sector for the tone of this guidance and for the way it was released. The guidance was regarded by sector lawyers as unduly prescriptive, and the lack of consultation and discussion was seen as high-handed. The outcry prompted the regulator to take the unusual step of amending its guidance.

One immediate concern is that Prins, while writing an essay in support of Britain leaving the EU, was simultaneously approving guidance which has been widely interpreted as seeking to discourage charities – many of which are in the Remain camp – from speaking out.

But beyond that, there was the issue that the guidance had been leaked to the Telegraph, which then accused some charities including Friends of the Earth of breaching it. Craig Bennett, FoE’s chief executive, said the charity was getting calls from the Telegraph well before the embargoed press release was sent or the guidance was published.

Another criticism of recent guidance is that there is little or no consultation with the sector ahead of publication; witness the regulator’s decision to issue updated reserves guidance the day after publication of the Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee report on Kids Company. And after Age UK was criticised in the newspapers for its deal with E.ON, new guidance on trading appeared almost immediately.

Sector bodies have urged the Commission to be more transparent about this new committee and have suggested that its membership should be reviewed.

Neil Cleeveley, chief executive of Navca, describes the committee as “clouded in mystery”.

Meanwhile Andrew O’Brien head of policy and engagement at the Charity Finance Group says that “given the importance of this aspect of the Commission's work, it should consider whether there is a case for admitting independent experts from the sector, particularly those from a charity law background”.

Blurring of the lines between board and executive

In recent years there have been repeated warnings from the National Audit Office, MPs and the sector that the Commission’s board is overstepping its governance function.

Unusually for a public body, the Commission’s board has the power, under the Charities Act 2011, to undertake executive activities. And the amount of time the board is able to spend on these activities has more than doubled since Shawcross assumed the chair.

In 2014 the Commission came under particular pressure and scrutiny in the wake of the Cup Trust scandal – in which it failed to draw attention to a charity used as a massive tax avoidance vehicle – and the National Audit Office wrote a highly critical report. In response, the then-minister for civil society, Nick Hurd, authorised a temporary increase in the amount of time board members could dedicate to Commission work from 18 days over a year to 22 days over a six-month period, up to September 2014. Crucially he rejected the request to make this a permanent arrangement. But the following January, Rob Wilson, the current minister for civil society, extended the arrangement indefinitely.

In a 2015 follow-up report examining the wake of the Cup Trust affair, the NAO said that the board’s hands-on approach was “justified” for the period up to mid-2014, but warned that it should not continue. Margaret Hodge, then chair of the Public Accounts Committee, added that the board had become “far too executive”.

NAO’s report shows that in the six months to September 2014, some board members were working much longer hours than others, with the range being between five and 27 days. It did not reveal which board members were most involved and more recent figures are not available.

Examples of what the board was doing during that time include appointing contractors, commissioning a report without enabling senior managers to comment and holding meetings with charity trustees.

Last year the Commission’s own report into its governance – conducted by Alan Downey, a former KPMG partner and the independent member of the Commission’s audit and risk committee - warned of the “risk of disconnect between the board and the rest of the organisation”.

It raised concerns that several members of the board were due to finish their terms at the same time, and suggested that another board member should be recruited, with IT skills and corporate board experience. No such appointment has been made, although the Commission revised its governance framework.

Perhaps the most graphic illustration of the power of the board is the Commission’s action over controversial advocacy group Cage, which board members viewed as supporting terrorism. The Commission asked charities to never again fund Cage, but the decision went to judicial review, and the Commission admitted it had no power to fetter trustees’ discretion.

Email correspondence between Fraser and senior staff were revealed at the High Court case, and showed that he had put pressure on staff to take action against the charities.

The Commission’s response

A Commission spokesman says: “The Charities Act 2011 gives the Commission its constitutional authority and sets out clearly the role of the board, which is markedly different to that of most other non-executive directors of public bodies. The Commission accepted the NAO’s recommendations to ‘keep under review its level of involvement in executive decision-making’ and to ‘complete the review of the governance framework and assessment of board effectiveness’.

“The independent review of board effectiveness concluded that the board should decide which ‘functions to reserve to itself and which to delegate to the chief executive and staff’ and that it ‘has the authority to intervene directly in operational matters, particularly those which affect the Commission’s reputation and performance’.

“As a result of the review, changes to the Commission’s governance framework were made. The framework, and a summary of the review of board effectiveness, are available on the Commission’s website. The Commission has kept the NAO informed of the progress it is making against the recommendations and expect it to follow up with the Commission in the coming months. The board continues to operate in line with the role set out in the Charities Act 2011 and its own governance framework.”

In short, then, the Commission is unworried by the large number of outsiders who believe that too much power has been vested in the hands of the supposedly non-executive board members, but it does not argue that this power shift has taken place.

Sector confidence in its regulator under threat

All this inevitably leads to questions over whether the right mix of people are sitting on the board and whether the current governance arrangements and appointments process is appropriate.

Sir Stuart Etherington now questions why the board’s time commitment has not been reduced.

“With an experienced senior staff team in place it is not clear why the board would continue to have hands-on involvement,” he told Civil Society News.

Last year NCVO published a discussion paper on the independence of the Commission outlining a number of options for reforming the process of appointing the chair.

Not only does the Cabinet Office appear to have taken no notice, it does not appear to have started the process of re-appointing or recruiting new board members. Given that five of the seven board members are due to complete their three-year term in the coming weeks, this should be a priority. But the Cabinet Office says only that no decisions have yet been made, and an announcement will follow “in due course”.

Etherington now says the Commission and Cabinet Office must urgently clarify the situation before the sector loses confidence in the regulator.

“In the interests of confidence in the Commission, we need absolute clarity and transparency on how board members are to be appointed as soon as possible,” he says. “It’s important that the board has a range of strengths among its members, including experience in charities.”

Asheem Singh, director of public policy at Acevo, says ““For some time, the Commission has appeared increasingly to be driven by single issue agendas. While being more interventionist and publicity-hungry, we have been concerned that its leadership has taken it to the point of no longer being able to do its primary job: of regulating and supporting our nation’s charities to meet regulatory requirements while they help vulnerable people at the same time.”

He adds that: “We cannot have a regulator whose governance arrangements are suspect. Effective policy making and guidance must be driven by experts, in concert with those who know and understand the charity sector, not by a small subsection of the regulator’s board. Action needs to be taken now to ensure the regulator gets its house into order.”

Dan Corry, chief executive of the think tank New Philanthropy Capital, says that having a strong regulator is important but that the problem of a perceived politicisation, both under Shawcross and the previous chair Dame Suzi Leather, “dogs the regulator” and “that perception is damaging; we have got to think about how we can get out of this loop”.

He suggests that having more people with a grounding the sector on the board would help improve its governance. “I don’t want to pack it - but there does seem to be a lack of people who have actually worked in a charity.”

Cleeveley says the recent behaviour of the Commission is making things harder for charities, and that while it’s right for the Commission to be a “critical friend”; at the moment the “Charity Commission is not getting the balance right and as a result they are losing the trust of those they regulate”.

Jay Kennedy, director of policy at the Directory for Social Change, says: “Many recent Commission decisions and statements have focused on ‘public trust and confidence in charity’ and trustees’ duties to consider and manage reputational risk. Yet the public statements of a number of board members raise questions about the Commission’s own impartiality and the confidence charities can have in its judgements.”

Wider changes to public appointments

While all this is going on the government is in the process of reforming the whole public sector appointments process.

The Cabinet Office recently accepted Sir Gerry Grimstone’s proposals regarding reform of public body appointments, which emphasise the importance of ministers playing a role in appointments process; calls for more transparency about how people are appointed, and makes recommendations for improving the diversity.

But Sir David Normington, who recently retired from being the Commissioner for Public Appointments, has criticised the Grimstone Review, warning that its proposals remove too many checks and balances and hand too much power to ministers.

Hancock, minister for the Cabinet Office, has already indicated that the government plans to implement the review’s recommendations.

What’s next?

When it comes to the regulator’s independence, perception is almost as important as reality. And at the moment it appears that there is a toxic combination of politicisation of the board, excessive involvement in executive matters, and a lack of understanding of the sector.

This situation cannot continue if the regulator is to have the confidence of the sector it regulates.

This piece has been updated to include comment from Acevo.