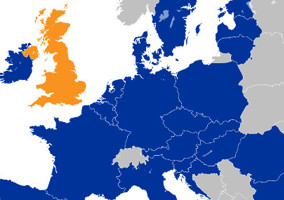

The continued uncertainty around Brexit means that any debate on it risks quickly becoming out of date or not reaching a meaningful conclusion. At the time of our discussion (mid-December), Theresa May’s withdrawal deal was still on the table, but the prospect of a no-deal Brexit on 29 March was very much increasing.

Panellists were working on a general assumption that the referendum result wouldn’t be overturned, but that there could be a second one. Whatever the outcome, there was a definite feeling that even if Brexit doesn’t happen, things will never be the same again, and the lessons that civil society needs to heed from the last two and half years will not become any less pertinent.

A number of the comments in what follows may need caveating with the “at time of recording” disclaimer, although the general points raised will remain (no pun intended) valid whatever the eventual outcome.

Funding

In amongst the uncertainty, the charity sector has attempted to quantify the effect of losing tranches of EU funding once the UK exits the EU. The Directory of Social Change has calculated an annual figure of £258m that will need replacing, though Daniel Ferrell-Schweppenstedde, policy and public affairs manager, says this is a conservative estimate. “We looked into funding that is under the direct management of the EU, and three structural investment funds. However, it is tricky to calculate the exact cost as large parts of European funding come with an additional set of things which are hard to replace, for example access to networks across Europe and knowledge exchanges.”

He suggests that the impact could be particularly acute for research charities, which might no longer be in a good position to compete for funding across Europe, and the wildlife trusts movement, which has in the past received 6 per cent of income from EU funds, via agricultural payments that can be invested in wildlife habitat.

Abbie Rumbold, partner at Bates Wells Braithwaite, has led the law firm’s response on Brexit. She told the panel about how the members of one of her clients, the Science Council, were concerned about not being able to collaborate with other bodies across the EU following the referendum result. “Research projects led by UK organisations have been affected, and the UK now risks falling behind as a knowledge centre. There are huge implications for the voluntary sector that don’t just affect the on-the-ground support services that politicians think of when they think of charities.”

She also says that a major concern is one of timing. “Lots of charities are already teetering on the edge of solvency. Any delay in moving from one system to another is a problem in the short term, even if things are smoothed out further down the line.”

The government’s proposed solution to fill the funding void is the UK Shared Prosperity Fund (UKSPF), which is intended to guarantee that UK organisations such as charities, businesses and universities will continue to receive funding over a project’s lifetime if they successfully bid into EU-funded programmes before the end of 2020. However, these guarantees are also clouded by uncertainty about how the funding will be distributed, and a feeling that there will be a lot of caveats that come with replacing such a large stream of EU funding with a national scheme.

The Charity Finance Group has made a number of public interventions on Brexit since the referendum, including a cost/benefit analysis on the impact on the charity sector. Its policy manager Richard Sagar is worried about the general lack of clarity regarding future funding. “There has been some consultation, but decisions keep being pushed back.”

He continues: “The feeling is that UKSPF money will be distributed by local enterprise partnerships (LEPs). But the concern here is that civil society doesn’t have a seat at the LEP table. How do we ensure that money goes to areas of priority for the sector rather than plugging gaps in business funding, or in local government where budgets have been cut considerably since 2010?”

There is a general view of LEPs not being fit for purpose, agrees Ben Westerman, senior EU policy adviser at NCVO. “UKSPF is not being sold as a replacement to EU funding but as a successor. For as long as there is no commitment to a figure, it will remain a concern that the amount the sector ends up with will be too small or affected by possible economic contractions.”

Kierra Box is the campaign lead on Brexit at Friends of the Earth, one of the few NGOs to explicitly come out with a remain position before the referendum. She says the advocacy group has continued to campaign on maintaining environmental protections post-Brexit.

“We are largely supporter-donation funded and only 1 per cent of our income comes from the EU. So we weren’t trying to protect our core funding. However, EU money has funded things that UK funders are historically bad at funding; for example, cooperation learning programmes. For some environmental groups, this funding is the only way they can access a European network. It is these add-on benefits that will be lost.”

Access to labour

Access to labour could also be a headache post-Brexit. Bates Wells’ immigration law team says that this presents problems for charities recruiting, who will need to consider whether EU nationals qualify to work in the UK, the cost of sponsor licences and the administrative burden of managing sponsor licences.

Sagar states that the proportion of EU migrants in the charity sector workforce is below 4 per cent, which is lower than other UK sectors, but crucially he adds: “This tends to be concentrated in healthcare and social care charities which are more likely to struggle to get staff to meet any future earnings threshold required to obtain a visa [currently proposed as £30,000]. An added problem is that EU nationals are often higher skilled but lower paid than their UK counterparts.”

Rumbold adds that the care sector is already affected by the sleep-in care issue, living wage, a local authority funding squeeze, and an ageing population. “As it stands, the possibility of sustaining care services is unlikely.”

She continues: “These are crucial long-term issues to deal with, and we probably should have been dealing with them anyway, although Brexit has heightened the situation. Culturally, how do we feel about the care sector? Does caring for older people have status? Is it a ‘good’ job? If we can’t resolve this then we will continue to be reliant on employing people from cultures where there is more respect afforded to caring roles.”

Westerman highlights that volunteering is not included in the EU worker figures. “There has already been a drop-off in EU nationals volunteering – it’s a cultural problem that they are not taking part as a consequence of not feeling welcome. A constant lack of clarity over citizens’ rights is concerning.”

Benefits of Brexit

On the positive side, Brexit could offer an escape from the bureaucratic hurdles that need clearing when “dealing with Brussels” for funding, with Westerman highlighting a big opportunity to remove some of them. Rumbold concurs with this assessment. “The issue with EU funding is that so many terms and conditions make it administratively burdensome. There is loads of compliance paperwork to meet rules and regulations that don’t always make sense. A UK fund free of that, which targets need and is delivered by those who understand needs in the local economy, could be beneficial.”

However, Ferrell-Schweppenstedde argues that while the red tape is horrendous, it underpins the rationale and process of setting up effective programmes, deciding what is funded, and how it is delivered. “The fact is that this is all agreed by 28 member states and is a huge machine for assessing what is funded. At a national level, once you pull out, that all falls away quickly.”

Box agrees. “One thing about bureaucracy is that being engaged in the EU process means you can be really sure where money is being spent. It might not be the best system, with too many forms etc., but it does provide evidence. When we talk about taking back control, we need to remember that the EU’s system has become best practice.”

Another possible benefit of Brexit is around irrecoverable VAT, which is currently estimated to cost the sector £1.5bn a year. As successive governments have fallen back on the “the EU won’t let us” argument for revising the VAT system, could this provide a windfall?

Sagar says the withdrawal document suggests that we can’t change VAT during any transition period, but that there is some possibility of doing so afterwards. However, he adds that it is highly unlikely that the government would remove the VAT burden due to the cost, especially given possible future economic stresses.

Westerman agrees that while VAT was one of the things identified as a big opportunity of Brexit, forcing any change through will be challenging. “Part of the problem is that if we end up in a worst-case-scenario recession, no government will remove £1.5bn from the books. These things are all at the mercy of wider economic trends, and while we can and will continue to push, they probably won’t happen.”

Preparation

Assuming that Brexit will bring some challenges, at least in the short term, how well prepared are charities for Brexit? Do they have their heads in the sand or is that unfair given no one really yet knows what will happen? Westerman says: “Head in the sand denotes intentional ignoring, but our impression is that this is more out of necessity. Firstly, lots of charities don’t have the resources to put into something as ludicrously complicated as Brexit. And secondly, information from the government hasn’t been forthcoming, especially to charities.

“However, in the last month or two there seems to have been a general awakening and acceptance to the fact that Brexit is happening, and that they should stop worrying and be prepared.”

Sagar agrees that while charities have Brexit on their risk registers, until there is clarity it is hard to know what else to do. While Box sums it up neatly. “It isn’t so much about having your head in the sand as being in the desert in a sandstorm, where there is sand everywhere, wherever your head is.”

Westerman advises charities to take advice and look at how the commercial sector approaches risk. “You can’t change the effects of economic contraction so it is important to scenario plan and shore up income streams, where possible.”

Box adds that Brexit is at risk of obscuring other issues. “First we have Brexit and potential economic contractions making us unsustainable, and then we have catastrophic climate change making life impossible. It is depressing when the focus is on income streams, and taking urgent immediate action on the environment is positioned as a nice-to-have once we have all financial issues sorted. The tumult around Brexit has already delayed the Environment Bill. There are bigger issues than Brexit that we’d like to concentrate on but we can’t.”

Liberal elite?

There has been some criticism of charities’ actions before and since the Brexit debate. Some, usually those that support remain, contend that charities did not speak out loudly enough before the referendum and have continued to be too passive.

Ferrell-Schweppenstedde thinks that there has been a missed opportunity in helping charities to put beneficiaries at the heart of the debate. “It is a difficult way of messaging so we need a better support structure to enable this.”

He adds that the future is about ensuring that civil society has a say. “We need to engage with other bodies and amplify our voice. I wonder whether the sector is too timid.”

Sagar agrees that as a whole, the sector could have been more united on key asks from the government, post-referendum. “It is to our detriment that we didn’t and we have been sidelined.”

Rumbold suggests that charities are often critical of themselves but it is very difficult as “there are more conflicts and different positions in the voluntary sector than the business sector”.

Westerman agrees that it is tricky because social change hasn’t been on this government’s agenda, but adds: “Civil society could have done more and should definitely do more in the post-Brexit environment, especially in a climate being sold as a chance for renewal and an opportunity for change. We need to be clear on what our voice is in shaping this supposed new country.”

Box identifies the “chilling effect of the Lobbying Act and its perceived influence on the ability to campaign. Small and medium charities think that space is shutting down”.

She continues: “And the fact that an election, or even a second referendum, could happen makes it really hard if you are bothered about risk. If you take a stand now you could get caught retrospectively by restrictions on campaigning periods if any vote is announced.”

Rumbold says: “There is a huge proportion of civil society which thinks that politics has no place in traditional charity, partly because of legal issues, but also culturally. But when we look at what civil society’s response has been, historically lots of organisations that have instigated social change have made a difference to the lives of people by being hugely political. If we want a response to underlying reasons for a leave vote, civil society will need to formulate one.”

She says faith-based organisations feel comfortable in reflecting their values. But she says: “The ‘liberal elite’ feels less comfortable about talking about their values to beneficiaries. Maybe we need to just say that politics has a place in civil society.”

Box states that part of the problem is that the sector moves quite slowly. “In political terms, things have happened very quickly since the referendum was announced and we can’t always respond in a fast and agile manner because of a structure where we need to get trustee agreement and talk to supporters. We are held to a higher standard of evidence and objectivity than businesses and it can take time to pull that evidence together.”

In Westerman’s experience, a lot of charities have wanted to come out and say Brexit is bad but realise that there is a distance between that position and the views of beneficiaries in communities who voted leave. However, Sagar argues that there is a difference in explicitly coming out and campaigning to remain, for example, and highlighting what different scenarios may mean for organisations. “There is always a difference of opinion between the views of members in umbrella bodies anyway, on any subject.”

Rumbold wonders whether such an approach would have an impact. “Anything that isn’t leave or remain doesn’t get noticed.” She also raises the issue of governance. “Trustees have to weigh up the benefits to beneficiaries from, for example, taking a remain position versus funding risks. A lot of organisations are dependent on individual giving, and coming out on something so divisive, one way or another, could be foolish as a fundraising strategy. Trustees are naturally risk averse, and a risky campaign strategy in the current environment would be hard to back.”

Box recalls the internal debates FoE had around potentially upsetting supporters when considering its position before the referendum. “All of these issues came up. We wanted to have evidence to persuade the board that was based on objective forecasts around what impact leave may have. We commissioned independent academic research. The trustees agreed that this was strong enough to back remain after a lot of internal debate. We then had to have conversations with supporters about how we put across that message.”

However, she admits that FoE’s stance comes with its challenges. “It is very hard to hold an evidenced-based position on details that aren’t clear and that are interpreted differently by different sectors or different MPs, or the same MPs on different days. So we have continued to commission research since the vote in order to update it and to allow us to keep saying we are evidence-based.

“But it becomes increasingly tenuous as it is based on aspiration, and you can find data to back any scenario. Even objective independent research will be questioned.”

Westerman thinks Brexit has posed interesting questions for civil society when taking up policy positions on all issues. “Politics is now based on a world where politicians of all parties are using populist statements to gain attention instead of facts and policy. The two main parties are internally fractured on Brexit. This makes policy statements really difficult as even rock solid evidence-based ones are ignored.

“This puts charities, already in a slightly gagged environment, in a difficult situation where they are caught between evidence and reality, and between policy and what their beneficiaries think.”

Out of touch?

There is also a question about whether charities are sufficiently in touch with their beneficiaries. Did the leave vote take the sector by surprise? And are charities part of some sort of liberal metropolitan elite which is out of touch with those they serve?

Sagar jokes “no, next question”, before saying: “It depends what you mean by charities. The vast majority are small and many are embedded in the communities where people voted leave, so they were probably better placed than many other sectors to see what was happening.”

However, he also cites research from the Young Foundation which indicated that less charitable funding was directed at areas that subsequently voted for Brexit.

Westerman agrees with the point about local charities, but adds that for those who represent the sector to government, there is “an uncomfortable truth that we weren’t ready for it, and there is a distance between what beneficiaries want and what we want”.

Box observes that shrinking statutory funding of civil society over the last ten years has led to more centralised structure. “Austerity has indirectly led to those that had strong networks losing touch with local organisations working in deprived areas.”

Final points

Wrapping up, Sagar ponders the opportunity cost of the sector being distracted from other issues, such as the government’s new civil society strategy. “HMRC’s focus has been elsewhere, but there are things like Making Tax Digital and IR35 [changes to the tax treatment of off-payroll workers] which we will need to deal with.”

Unfortunately, Box believes there is cause to question the notion that Brexit will all be finished come 29 March. “It won’t. Either there is another vote and we have possibly wasted nearly three years, or we prepare for ten years of trade negotiations.”

Sagar adds that the sector needs to go back to asking why the referendum result happened. “It was supposedly all about taking back control, but there is no evidence that things will actually be any different or improve for the majority of society. Will people really feel that they got what they wanted? We need to focus on winning the peace as well as the war.”

Westerman concludes that the biggest challenge for civil society going forward will be working in a world of division. “Woe betide the next PM, be it Corbyn, Johnson or a broomstick. Conducting policy in an environment where disagreement is unacceptable and compromise is corrosive will be nigh on impossible. Charities need to ensure that their voices are clearly heard.”

With thanks to Bates Wells Braithwaite for their support with this feature

Related articles