Governments and central banks around the world acted quickly to mitigate some of the consequences of the Covid-19 crisis, with interest rates cuts, loan guarantees and additional spending to preserve jobs. But, we are all too well aware that charities are feeling the effects already, both in their own charitable work and in their finances. Fundraising events have been cancelled, donations have fallen, charity shops have closed, and additional expense has been incurred in providing home working technology for staff, to name a few of the effects.

This is to say nothing of the impact on beneficiaries and how they are served. Many charities will need conversations about how to deal with the organisational and beneficiary needs here and now, and the longer-term implications of actions taken today (more on that later). The government announcement to support the sector to the tune of £750m, in addition to charities being able to furlough their staff, is welcome. However, we know that this will not alleviate all the widely felt impacts upon charities, their income and their sustainability.

For many charities, investments also form part of their long-term sustainability plan, with contingency funds designed to be available in times of trouble. One of the challenges when market values have fallen, however, is the ability to take the long-term view we always talk about. If you have been invested for many years, you will have enjoyed investment gains that may be considerable. You may choose to look at that long-term growth and decide that now is the time to take some of those gains to keep the show on the road. This is psychologically hard to do when you will now be a “forced seller”, removing funds when portfolio values are lower. This should be a topic of conversation not just for the trustees and finance team, but also something for you to discuss with your investment manager.

For grantmaking charities, there are already some really good examples of how they are adjusting their grantmaking activity, both in terms of grants already made for one purpose being permitted to be spent on another, such as core costs, and regarding announcements on how to apply for new funds being awarded during this difficult time. We are aware of previously awarded project funding having criteria loosened to cover core costs, IT equipment and increasing spending on the beneficiary front line. Such charities will themselves be affected too as the crisis is also having an impact on the investment income.

Future investment income

Early on in the coronavirus crisis, NCVO estimated that over just 12 weeks charities in the UK will lose at least £4bn of their income. That is more than the top 300 foundations give in a year, and NCVO added that the lost income could be much higher.

What are the implications for those who rely upon their investments to generate the income to help fund their operations or make grants? What follows is some of Brewin Dolphin’s thinking, recognising that the situation is very fluid.

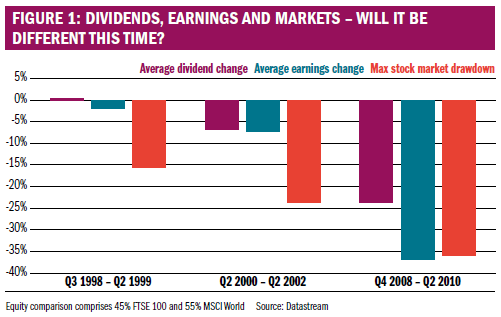

Historically, UK companies in particular have been loath to cut or cancel dividends, and hence payouts have tended to be far more resilient than earnings (profits). Figure 1 (at the bottom of this article) shows the change in dividends, earnings and share prices over each of the last three recessions, where dividends have tended to be remarkably stable even in the face of severe reductions in earnings. If this relationship were to hold true, then it suggests that dividends may be affected less than some other areas of your charity’s income. But we are now seeing a great deal of news of dividend cuts and cancellations, a reflection of the precipitous decline in earnings for a number of companies.

One feature that stands out as unusual is the size of the dividend cuts during the global financial crisis in 2008 to 2010. This was a deep and long-lasting recession, so that is part of the reason why cuts were so significant. Bank bailouts also came alongside massive pressure for banks to reduce dividend payouts.

The big question is if this historical relationship will hold or whether we will see far greater reductions in dividends this time around. Government bonds used to yield more than equities before the global financial crisis, whereas now they yield about a tenth as much. Companies may feel less pressure to continue to make these payments when other forms of income have declined. From a UK investor’s perspective, things were not looking strong in any case, with a dividend cover ratio (which shows how many times companies can pay their dividends out of their profits) below 1.5 suggesting that dividends are vulnerable to a company’s ability to pay them. They are also more vulnerable than they have been historically.

Many companies have already announced that they are cutting or suspending their dividends, particularly in sectors which have been directly affected by the government guidance around social distancing. These include travel and leisure (eg Compass Group, Intercontinental Hotels Group, Marstons), general retail (eg Kingfisher, Marks & Spencer, Next), housebuilding (Taylor Wimpey, Persimmon) and media (ITV).

Such sectors typically represent only a small fraction of the total forecast income in our portfolios, if held at all. Even those that have closed their 2019 accounts and declared their dividend payout have the option to subsequently reduce or cancel them to conserve cash. Lately, however, we have also started to see some companies that are indirectly affected cutting their dividends, including banks, acting under pressure from the regulators, and property companies which are facing demands for rent holidays.

These companies tend to represent a larger proportion of the income generated by the FTSE 100.

Oil companies BP and Royal Dutch Shell (RDS) account for one-fifth of total dividends paid by FTSE 100 companies, but are reeling from the sharp fall in the oil price amid dramatic falls in demand. However, both may be able to maintain their dividends longer term given their payout commitments, access to finance, and with the oil price expected to rebalance in a couple of years. RDS has reported recently that it intends to maintain the payment, and has cancelled share buybacks and cut capital expenditure in favour of retaining the dividend. RDS has an unbroken dividend record since 1942.

Diversification

Charity portfolios are usually globally diversified and hold other asset classes, such as fixed interest or alternatives, which are likely to be less affected or which could even see near term income growth. We hope that a reasonable proportion of portfolio income will show some (but not total) resilience through this period.

Your income prospects

It would be prudent for charity investors to reduce their investment income forecast for the coming year, possibly for several. It is difficult to put a number on this decline in income, especially as the situation is so fluid, but a reduction in investment income at least 10% to 20% this year, and perhaps more next year, should be considered. Just bear in mind that this is just an overview thought based on what we knew during the early lockdown; conditions could worsen if the pandemic lasts longer than anticipated. Each portfolio is different, so a careful analysis of your own investments will vary from any average impact.

Investment income will almost certainly hold up better than the capital values. We also need to bear in mind the difference between income in percentage and pounds terms. Clearly, those charities which have to spend capital during this time (with good reason) will be shrinking the pot that produces the pounds in the future. The percentage figure will produce fewer pounds from a lower level investment value.

Looking beyond the crisis

It is always important in times of turbulence to maintain your strategy – you set it as a long-term and appropriate approach for your organisation with good reason. Nonetheless, use current cash wisely and be realistic about what you can achieve.

With an Institute of Fundraising survey finding that on average charities expect their voluntary income to halve and their trading income to decline by a third during the crisis, such charities which are fortunate enough to have investments are likely to call on them to supplement their budgets.

Operational and working capital for day-to-day cash flow management are not the same as long-term investments, the latter being unlikely to be called upon at short notice. This, for many, will be a stark reminder that operational reserves are there to be called upon as a supplement, sometimes for survival. Many charities will need to revisit post the crisis how they allocate these short and long-term assets. What is a truly long-term investment suited to stock market investment (and capable of producing that important budgeted income), and what should be kept in shorter term investments in order to act as a true reserve fund? There has been a muddying of these two waters, and planning discussions are likely to refocus the minds on these distinct elements of a charity’s assets.

Ruth Murphy is head of charities at Brewin Dolphin