Economists are not known for their predictive abilities. Indeed, one of the first economists to receive a Nobel Prize, Frederik Hayek, warned the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences against the creation of such an award. Economists, he argued, could never make predictions as physical scientists could since economies were too complex and at the mercy of human behaviour. This may be so, but it doesn’t stop economists from forecasting and investors poring over these prophesies.

The path of interest rate changes, the next release of unemployment figures or - particularly of concern at the moment – the latest inflation data, help us to understand the state of the economy and can move markets. However, the constant stream of data, snapshots of changes month by month or quarter by quarter also creates noise. For long-term investors it is important to look through this noise to identify the dominant trends.

Having a longer-term investment time horizon means we can afford to be a little more sanguine about the oscillations of markets over days, weeks and even months. In a world where the movement of a stock price in fractions of a second matters to some market participants and many more have a time horizon that extends little beyond the next quarterly earnings, we believe that patience is an advantage.

The end of the year provides a natural point to reflect on the past 12 months, take a step back from the short-term noise and to look for themes that we can be more certain will continue to shape the investment landscape over the coming year(s).

Market leadership (probably) never persists

From an investment perspective, the last decade has been all about the US. Over the past 10 years the annualised total return from US equities has been an impressive 13%. Comfortably beating the 9% delivered by global equities and way ahead of the 4% from the Asia Pacific region (based on the annualised total US dollar return of the S&P 500 (USA), the MSCI All Country World Index and the MSCI Asia Pacific Index over 10 years to 31 October 2022).

Within the US, the standout story was the emergence and dominance of a small number of technology companies – notably Microsoft, Facebook parent Meta Platforms, Apple, Amazon, Netflix and Google parent Alphabet. By the end of 2021, these six companies made up over 22% of the US stock market index by market capitalisation (according to the S&P 500 index). These mega-cap companies had established dominant positions across geographies and a seemingly unassailable market position.

2022 was a very different story and technology companies suffered more than most. The rebranded Facebook – now Meta, saw some of the steepest declines, seeing its market cap fall an extraordinary $681bn over the first 10 months of the year. Having built the Facebook platform, which at the end of 2021 had 2.9bn active users, investors are now increasingly worried about a decline in the app’s popularity. To counter these concerns, the firm is forecast to spend between $34-39bn on product development in 2023. CEO Mark Zuckerberg said in June 2022: “We hope to basically get to around a billion people in the metaverse doing hundreds of dollars of commerce, each buying digital goods, digital content, different things to express themselves.”

As yet, its bet on this Metaverse – a new 3D form of the internet – has not convinced investors. Proof perhaps that seemingly unassailable market dominance is ephemeral and should never be taken for granted.

Challenging the status quo

If the past decade was all about the creation of global platforms, how will the next decade look? Proponents of Web 3.0, which is a vision for the future of the internet, argue that we could see a challenge to the status quo for many of the dominant technology firms and their business models.

When the internet first appeared, its success was based on the idea of open access technology and the underlying code was made free to use and open to all. This open architecture ensured rapid growth, but the next evolution saw companies building proprietary applications and platforms effective at capturing and monetising data. A small number of companies came to dominate, while providing products and services that became embedded in the way we work and play, generated enormous revenues through the capture and sale of our data. Their dominance looked unassailable. In his 2021 book The Platform Delusion: Who Wins and Who Loses in the Age of Tech Titans, Columbia Business School professor Jonathan Knee challenged this assumption arguing that incumbency doesn’t mean longevity.

Cryptocurrencies are a product of this new decentralised approach, which Web 3.0 proponents argue will usher in a new economic system. The early rush of enthusiasm for these new assets was met with scepticism by some. In 2017, the CEO of JP Morgan Chase dismissed Bitcoin as “worse than tulip bulbs”, a reference to the 17th century Dutch bubble in tulips.

Widespread interest in these virtual assets has been tempered following steep falls in the value of many cryptocurrencies in 2022. Hopes that the likes of Bitcoin might provide an effective hedge to traditional asset classes also faded in the first six months of the year when the price collapsed alongside steep falls in equity and bond markets.

Cryptocurrencies have attracted a lot of attention, but of more interest, perhaps, is the technology that lies behind them – blockchain. Blockchain is a technology that enables transactions to take place outside of the established banking system. The big banks whose business models could be under threat from a new decentralised financial system are not standing idly by. Many are investing heavily in blockchain. Interestingly the first cross-border transaction carried out using blockchain-based decentralised finance was carried out in October by none other than JP Morgan.

The eclipse of the age of globalisation?

The early 1990s saw the collapse of the Soviet Union and a sense that western liberal democracy would become what political scientist Francis Fukuyama called “the final form of human government”. China also entered a period of rapid economic growth as the government pursued a policy of modernisation and economic openness. Digital communication and the arrival of the internet helped foster international connectivity and increased flows of goods and services between countries. Businesses sought to overcome the barriers of national borders. In this way, a company headquartered in California could sell a product made in China to a customer in Spain, while paying tax on the transaction in Ireland.

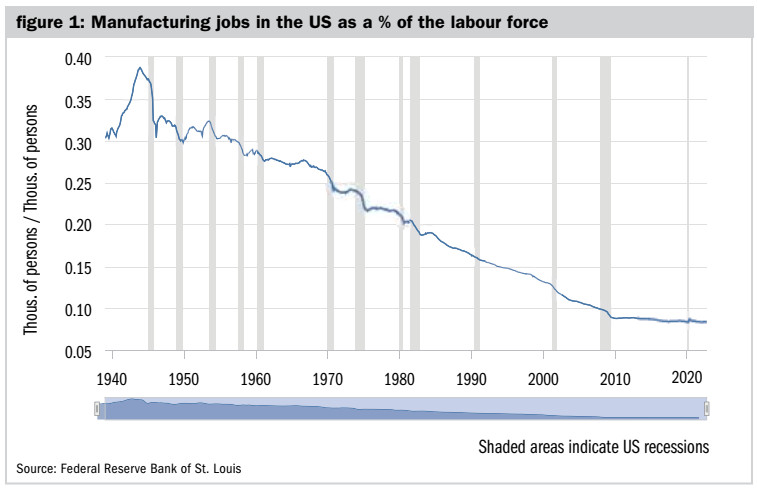

Globalisation has shaped the world in so many ways. The emergence of ubiquitous brands such as Apple, Coca Cola and McDonalds which can be found in almost any country is a very visible sign. But one of the most far-reaching changes has been the shift of manufacturing from the developed world to the less developed world. Figure 1 shows the steady decline in manufacturing jobs in the US after the second world war.

Emerging economies grew a manufacturing capability built on cheap labour, providing the western world with cheap goods and services, and consequently, low levels of inflation. The flow of goods from Asia to the West also helped to lift hundreds of millions of people out of poverty. But in the West, the economic changes brought about by deindustrialisation have generated numerous social challenges.

Stagnating wages and a sharp rise in income inequality have been felt in many parts of the developed world. Dissatisfaction with the massive social and economic impact of deindustrialisation was a key factor behind the success of Donald Trump’s Make America Great Again agenda. His government’s anti-China rhetoric, the fulfilment of a promise he had made on the campaign trail, led to the imposition of trade tariffs and policies aimed at slowing China’s progress. The Biden administration has not backtracked on this approach and in October announced far-reaching legislation aimed at restricting the supply of advanced technology to China.

Investors cannot ignore increasing political and geopolitical risks

Growing distrust between countries has also been mirrored by increasing divisions within countries and a more volatile and divided political backdrop. For many years, changes in governments were of limited interest to investors. For much of the past three decades most of the dominant political parties in the developed world occupied the centre ground. This has changed as radical ideology has become more mainstream. Investors now have to pay more attention to political discourse as we in the UK became all too aware during the short-lived government of Liz Truss.

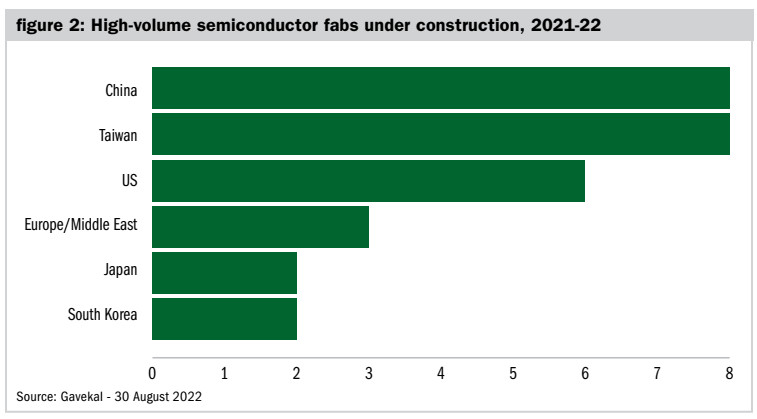

It isn’t just the US eyeing China with greater suspicion. Here in the UK, the National Security and Investment Act. which came into force in 2022, was used to block the acquisition of a Welsh semi-conductor manufacturer by a Chinese-owned business. Technological capability has become a matter of strategic importance.

The breakdown of the existing global trading system will have widespread effects on economies. Some of these changes have been accelerated by the impact of the Covid pandemic, which revealed the fragility of the existing economic structure. Companies will have to adapt global supply chains threatened by new tariffs and trade barriers. The Japanese investment bank Nomura estimated that Vietnam stood to gain an additional 8% of GDP growth from the imposition of tariffs on Chinese made goods by the US in 2019 as companies shifted production.

Moving manufacturing is costly and some countries have built up a large pool of skilled labour and a technological edge which cannot easily be replicated. The impact could mean higher costs for businesses and as a result lower corporate profitability. The increased friction involved in diversifying supply chains to different countries could also generate a higher natural level of inflation.

One effect of deglobalisation likely to accelerate is reshoring – the practice of bringing manufacturing back to a company’s domestic base. Consulting firm Kearney found that 79% of the executives it surveyed in 2021 with manufacturing operations in China had either already moved part of their operations to the US or planned to do so in the next three years.

Reshoring makes more sense in the production of hi-tech and high-value goods where production is less dependent on large pools of unskilled labour. It is much more challenging for companies producing lower cost items such as in garment manufacturing where labour makes up a large part of the total costs.

The robots are coming

One solution to the challenge of higher labour costs and the lack of specialist manufacturing skills in places such as Europe and the US is to rely more on automation. This is particularly relevant for companies operating in countries with a demographic challenge brought about by a declining birth rate and an ageing population. The EU is facing just such a challenge. Over the period 2019 to 2100, Eurostat’s projections suggest there will be a net reduction of 115.0m inhabitants as a result of natural changes in the population – even assuming positive net migration from outside the EU.

Automation is already having a major impact on the way retailers operate, improving inventory management and the speed at which a wide range of products can be delivered directly to customers’ homes. The International Federation of Robotics estimates that the number of robots operating globally reached 3.5m units in 2022 and is forecasting rapid growth – particularly in China. The country’s 14th five-year plan released in March 2021 specifically called for a doubling in the number of robots in 2026 compared with 2020. Rapidly rising labour costs and a shrinking working age population have driven this focus.

At the start of this article, I had a dig at the poor predicative abilities of economists, which was unfair. The truth is we are all poor at forecasting the future. In their 2016 book Superforecasting, Philip Tetlock and Dan Gardner showed that the average expert forecaster performs no better than a dart-throwing chimpanzee.

We wouldn’t want to lose out in such a contest with the chimps and so will refrain from making any detailed forecasts on the path of markets in 2023. Instead, as investors we will continue to do what we have always done by aiming to build portfolios that have sufficient resilience to withstand the setbacks which we will certainly encounter in the year ahead, while remaining on the lookout for opportunities.

The challenging experiences of 2022 and the darkening clouds of a slowing global economy make it easy to be pessimistic about the prospects for 2023. However, we have faith in the ability of the companies in which we invest to overcome the challenges of a recession and to emerge stronger. These companies have demonstrated resilience in the past and the capacity to remain relevant while the trends to which they are exposed change.

Patrick Trueman is portfolio manager at James Hambro & Partners

Charity Finance wishes to thank James Hambro & Partners for its support with this article