Charities exist to do good. As a result, sector leaders have always been concerned about how to bring relief to people in distress and get support to those who need it.

In recent years, however, questions about empathy and decency have changed. They are no longer focused just on beneficiaries, but also on the treatment of staff and volunteers. Evidence from a range of scandals over bullying and discrimination – ensnaring Save the Children, ActionAid UK, NCVO and many others – shows that some charities have failed their own people, even while promising to be a force for good in the world.

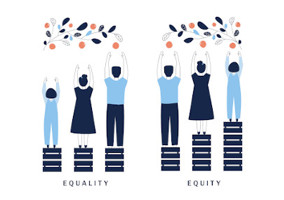

In response, campaigners have forced equity, diversity and inclusion (EDI) work to the top of the sector’s agenda. There are ad-hoc advocacy groups, hashtags and WhatsApp chats. Charities have reacted, too, with public commitments to improve how staff are treated and – in the case of some of the biggest organisations like Cancer Research UK and Wellcome Trust – clear goals for improving race and gender equality in particular.

One part of the jigsaw is often missing from these debates, though.

The moral power of EDI work is not enough on its own. Reform costs money, and even the most pressing social justice issues are subject to competing financial priorities. Charity finance teams face tough decisions to help their charities address EDI. They belong at the centre of the discussion.

A culture of people thinking about EDI

“It is evolving, how we pay for these sorts of things,” admits Thomas Matthew, who is director of finance and resources at the national poverty charity Turn2Us, and also sits on its EDI committee.

The committee, which was set up three years ago, consists of 10 people from “all levels and all departments” of the charity, Matthew explains. It has its own direct budget – a fairly modest £5,000 a year from central coffers – and acts as a link to the board through a trustee with their own EDI responsibilities.

He stresses that the committee is not a substitute for existing work inside Turn2Us. “It can’t replace HR,” he says, “it can’t replace the senior leadership team.” Instead, it has “its own special function within the organisation”.

Matthew continues: “One thing it does is it develops and drives forward initiatives and ideas around EDI – so it has brought to the organisation training that all staff have done around LGBTQI+ [support], and we’re doing some disability training in the coming months. It has created things like safe spaces, so people with different characteristics form groups where they can talk with each other about their experiences in life and in the workplace.”

Plus, the committee acts as a “sounding board” for the rest of the charity. “When there are charitable delivery or research initiatives, or policies being written internally, often those types of things are brought to the committee to help them look at it through an EDI lens. It also acts as a point for people in the organisation to bring ideas, reflections, proposals, those kinds of things, and also, where appropriate, problems and issues.”

Matthew gives the example of new blind-shortlisting recruitment software, which tries to eliminate unconscious bias when selecting new staff. The EDI committee helped recommend the change, while the software itself was paid for from the HR budget. This means that the charity’s small outlay to resource the committee helps ensure equity questions run through the mainstream of its finance decisions.

“In the budgeting process, we try to think about EDI not as a single centralised thing [sitting] with this committee, but how it impacts all the teams and budgeting happening in those areas,” he says. To other charities that may be considering their options, Matthew recommends: “I just think that organisations have a responsibility to make this part of their DNA.

And they need to make that work in ways that they can, within the financial limitations that they may have. [They should] consider creative ways of addressing it, which does not cost money that they can’t afford.”

Time is money

This is a view shared by Jon Cornejo, who worked in the charity sector for more than a decade before establishing himself as an anti-racism consultant.

Cornejo argues that there are plenty of tools for charities committed to making progress on EDI, but one place to start is budgeting. Other, more expensive options may not yield useful results, he warns, especially at the beginning of the EDI process.

He says: “When we look at funding, we think of funding the work, funding the project, getting consultants in. All of that is really valid – but we often forget that time itself is a resource, something that costs money. We need to be willing to give that time and spend that money on people doing a bit less of their usual role in order to be able to focus on it [EDI].”

Cornejo adds: “That work takes a lot of time and effort, and I think if it comes piled on top of an already busy workload it will just become the first thing that falls off. I see this time and time again, where organisations invest in things, but they haven’t invested in their people and given them the time and space to really put it into practice. It just doesn’t happen, and nothing really changes. Looking at prioritisation and time is the key thing for me.”

Only then, he suggests, should charities start thinking about investing in bigger EDI initiatives like bringing in consultants or reforming whole departments. “I think a lot of the time [charities] are looking to invest in consultancy or training in order to check a box and be able to say to our boards, our members and our supporters: ‘We are anti-racist, we are going on this EDI journey’.”

This is the wrong way around and, by implication, a waste of money, Cornejo suggests. EDI conversations must “start off within the board meetings, within leadership meetings, and with questions like: ‘Where are we at? What is the problem? What are we hearing from our staff? What are we seeing?’”.

Steps to take

These sorts of discussions can also help foundations become fairer and more effective in their day-to-day work of giving out grants and loans.

An ongoing EDI audit at the Esmée Fairbairn Foundation, for example, convinced it to remove an existing rule barring applications from charities where annual turnover was under £100,000. This rule had a disproportionate impact on the very charities which are already affected by social inequality, explains Sharon Shea, director of portfolio at the Foundation. “Many Black and ethnic minority organisations, and organisations led by racialised communities, have historically been underfunded,” she says, adding that “historic underfunding clearly has an impact on organisations, their annual turnover, and the strength of their balance sheets”.

The move helped address a problem identified by the Foundation’s audit: that it sometimes “thinks about the world from a funder’s perspective, and not necessarily from the perspective of some of the organisations that are locked out of our funding priorities”.

Other charities, alert to this challenge, have started asking similar questions in their own corners of the sector.

Take Music Masters, a music education charity that works with both school children and teachers. It has developed an initiative called I’M IN, designed to help organisations across the industry start thinking about their equity work.

In terms of the cost to get the project off the ground, Music Masters received a grant of around £50,000 to pursue the scheme, explains Roz de Vile, its chief executive. Off the back of this, Music Masters created two versions of I’M IN, and now offers partners in the industry both a free toolkit to lead initial conversations and a more intensive, paid-for consultancy process.

De Vile describes the toolkit, rolled out last year, as a “provocation” for leaders. It is focused on making organisations think about key issues around motivation, leadership and accountability. Echoing both Matthew and Cornejo, she argues that this sort of thinking is an essential building block for all EDI work. “If you’re just saying: ‘Right team, let’s get unconscious bias training!’ it is not going to do much unless you really understand the context and the issues and why you’re doing that.”

If music charities decide on paid-for EDI consultancy, de Vile ticks off the things they can expect for their £750 fee: time with a consultant before and after a dedicated workshop, then a series of expert recommendations, and a follow-up to check on progress. (Needs differ, of course, but this appears to be a bit of a bargain. Charities are wary of saying how much they pay for EDI consultancy, but in some high-profile cases the costs are well into five figures).

Music Masters decided to create the EDI support “to give the sector a bit of a wake-up call”, de Vile says. The free tool, trialled last summer, became a more dynamic way to impress upon the industry the “need to practically do something in order to welcome these amazing, talented young people into the sector – because, so far, it’s always felt like someone else’s problem that the concert halls are filled with white people”.

She was pleasantly surprised by the level of interest. “We had 60 organisations sign up for the trial, when we initially thought it was going to be 10 to 20,” she explains. I’M IN has been adopted across the sector: “We had schools, we had music education hubs, we had charities, but we also had major orchestras and, from across the UK, ensembles, venues, publishers, record labels, a really wide spread of organisational types and sizes.”

Financial risk

Consultants can’t do much for charities which aren’t willing to put in the work, according to Cornejo. Experts can soon tell whether or not a charity has put the time in, he says. “I talk to a lot of different leaders in my work, and I think you can tell when someone is really looking to change and improve the organisation, but don’t necessarily know how to go about it. It’s a very different feeling to when someone just wants you to check a box for them.”

This means that charities broadly have three choices when they think about financing EDI work. They either find new resources to pursue it, accept that there is an opportunity cost when prioritising EDI from existing budgets, or commit to an even bigger financial risk.

The latter is certainly true for Music Masters, which had to shoulder all the risk of introducing I’M IN. “I mean, we didn’t have any funding to actually run this thing in its trial form,” de Vile admits. “We just kind of did it anyway, which wasn’t amazing for our budget but was really great for those organisations.

“We are not doing this to make money from it. We are doing it because of the futures of our young people and their work, all around the UK, who need that opportunity and that support.”

What are boards expected to do on EDI?

Last year, experts updated the Charity Governance Code to include guidance for how trustees approached EDI.

The code acknowledges that EDI work can be time-intensive and will eat into trustees’ resources, but says it will “help a board to make better decisions” and ensure a charity “is more likely to stay relevant to those it serves and to deliver its public benefit”.

It recommends that boards at large charities should look at four areas of work:

- Understanding systems and culture at their charity.

- Setting realistic plans and targets.

- Taking action and monitoring how the charity performs.

- Transparency on what has happened and what charities have learned.

Boards are expected to define their own understanding of EDI, fitted to the context of the charity’s work, and set appropriate policies and goals. Trustee recruitment should try and “address imbalances” in board representation, and boards should set aside time to review and discuss together what they have learned from their ongoing EDI work.

Transparency is crucial, argues the consultant Pari Dhillon, who worked on updating the Charity Governance Code. “Ideally together we will create a sector in which people are sharing their progress, their performance and what they have learned from their challenges,” she wrote last February. “This transparency can feel nervewracking but when done well it gives us public accountability and allows others to learn alongside us.”

Guidelines for trustees at small charities encourages similar practices where possible, while encouraging boards to set EDI tasks and goals which are “realistic” for the size of their organisation.

Related articles