Like many investors, charity trustees may be trying to assess how much equity risk their funds are exposed to, but traditional measures of risk might not tell the whole story.

Equities – why own anything else?

According to research by Professor Shiller, US equities have delivered a real total return of around 6.5 per cent per annum over the last 150 years. Dimson, Marsh and Staunton of London Business School estimate that global equities have, since 1900, delivered 3.2 per cent more than bonds per annum. This illustrates the compounding effect of an equity portfolio – investments in growing businesses in a growing economy, rather than fixed obligations. The price paid by investors for the extra return from investing in equities is the extra risk (sometimes called the equity risk premium). This risk merits discussion.

Volatility and beta are not risk

University finance courses teach the capital asset pricing model (CAPM), which says that investment risk is equivalent to the volatility of a stock. To market practitioners, much in the CAPM seems odd, particularly this claim that the market price of an asset moves about in a way which reflects accurately the investment’s volatility. We know that the volatility of financial assets varies wildly over the cycle (think 2008), and so historic volatility is no guide to future volatility. However, CAPM is based on perfect market theory which sounds, to a market practitioner, much as a biochemist describing cell division sounds to a farmer.

Surprisingly, many large investment houses model the risk in their portfolios entirely through beta-based modelling. Beta is volatility. Furthermore, there are many versions of beta to choose from and they all vary over time. Relying principally on a black box version of a dubious theoretical version of risk seems unwise. Indeed it may give false comfort. Perhaps it is no great surprise that large investment houses seem to lose control of capital risk during market shocks.

Permanent loss of capital

These compelling returns from equities, of course, are very long-term in nature. Risk is different for different investors with different time horizons. Investors who find themselves overstretched when markets fall may find themselves forced to sell their equities at the worst moment. However, many investors such as endowments and pension funds have the benefit of very long holding periods. They can and should sit out bear markets, though they cannot ignore periods of inflation. For long-term investors, risk is therefore not about volatility, but about avoiding investments which may lead to permanent loss of capital.

Companies can go bust, leaving their equity worthless. The extra risk investors take by owning equity is made up for by the extra return noted above. However, it should not be forgotten that corporate bonds have also been known to fail and sovereigns to default. I have a few Imperial Russian bearer bonds in a drawer. To be fair, they didn’t suffer a permanent loss of all capital – dealers in antiques and curios still have an interest.

Over the long term, many individual equities will go bust. It may be of interest to note that only GKN and Tate & Lyle survive from the original 1935 FT 30 index. Many others – Fisons, Pilkington, Bass – were taken over at prices very advantageous to their shareholders. A few – such as Austin Motors (via British Leyland) and GEC (via Marconi) – saw a permanent loss of capital. The coal mines, meanwhile, were nationalised while textiles downsized.

And how to avoid it

To minimise the risk of permanent loss of capital, it seems worthwhile to follow the following rules. First, is the industry seeing technological disruption? You don’t have to choose to own car companies, just to avoid manufacturers of horse-drawn carriages. Looking at new technologies as threats to the existing order, rather than principally as profitable investment opportunities, seems worthwhile. Owning Priceline (Booking.com) has been good – but so has avoiding Tesco.

Second, beware of indebted companies. When equity managers describe quality long-term holdings they generally focus on the volatility of income and stress how large a moat, or barrier to entry, their companies have. Moats, however, can be bridged by new technology. Also, reliable cashflows can encourage managers to take on excess debt in their business (equally, variable cashflows can encourage prudent balance sheets). Some forget, for instance, that the supposedly reliable food manufacturing industry has seen frozen vegetables come and go, diet fads and health scares. Where is United Biscuits today? Who remembers that the KitKat bar was within weeks of being withdrawn in the 1960s? However stable the earnings of a company may seem, bad luck, bad management and excess gearing may put the equity value at risk.

The third risk of permanent loss of capital is governance. A sensible approach to valuation compares declared earnings with recorded cashflows. Dubious companies frequently report plentiful earnings and yet seem never to show an increase in the cash on their balance sheet – remember Enron. Again, fundamental analysis can help identify unproven or dubious business models. In emerging markets, it is best to avoid good companies if they are trading in countries with bad governments. There is no merit in making a successful investment if the currency becomes devalued or suspended or if a state fails to support property law.

Applying the test to today’s large companies

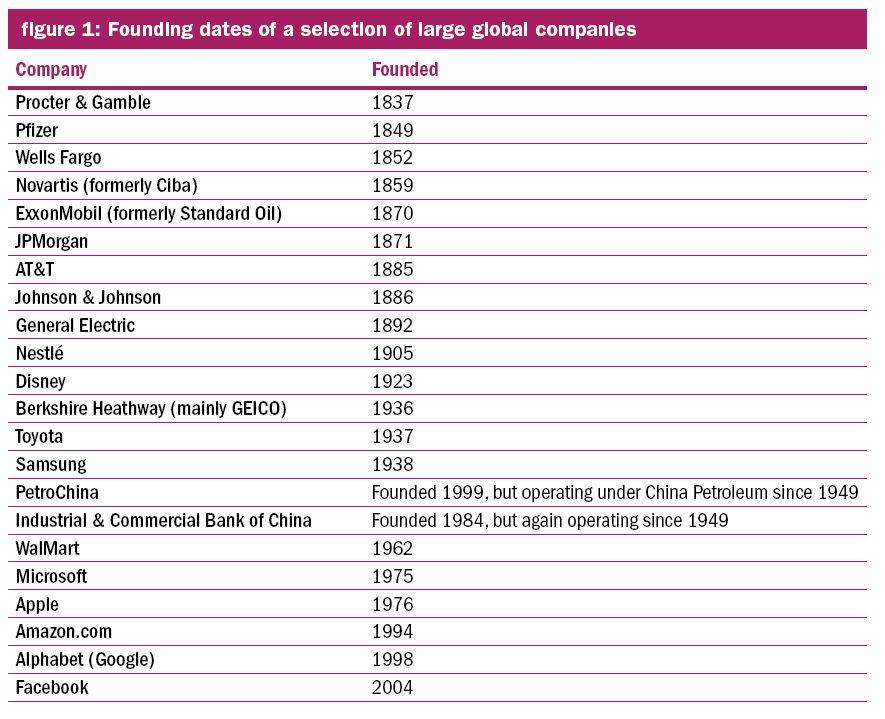

Given the equity returns compounding over a century, it is interesting to look at some of the largest companies in global equity markets today. It is notable how young many of these are, but also how financially robust.

So the mass of the global equity index is made up of companies founded only a few decades ago – and these investments are the base for funding charities’ grantmaking and pension liabilities decades into the future. A quality investment should presumably have demonstrated its ability to survive a few economic cycles. It is notable that, although widely lauded quality companies such as Nestlé have lasted decades, so have banks, currently regarded as low quality. Even the drug companies in the list were chemicals companies (regarded as trading stocks) in days long ago.

Durable investments generally have barriers to entry. As mentioned above, these can be eroded by technology and are little use when an industry goes into decline. Looking at this list of very large companies, it is notable how many rely on network effects as their barrier to entry. It is not very difficult to design a website such as Amazon.com, but it is almost unimaginable that anyone will compete with it on breadth of offering. On the other hand, it is not unimaginable that many of us will tire of Facebook over time.

How active equity management helps

We believe that active equity managers have two key roles. First, to avoid the index constituents that may suffer a permanent loss of value, either through going bust or through being in challenged industries.

Second, to balance the portfolio between sectors and regions in a way the index does not. We want equity portfolios to preserve capital not just through the known challenges ahead – but also through unexpected events. This requires fund assets to be spread across different types of investments which respond differently from changing economic conditions. We also try to avoid letting the average multiple of cash flows of the whole portfolio rise too far.

Portfolio balance helps – the example of automation stocks

Portfolio balance comes from investing in automation. These new automation investments present us with an exciting investment opportunity, while having the added advantage of being lowly correlated to the rest the portfolio (being mainly Japanese exporters). Machines have, of course, been replacing labour since the Spinning Jenny in 1764. So what has changed to make us want to invest more in automation now?

There are three new dynamics. Firstly, as the price of robots has fallen and their quality improved, they become cost-efficient for more tasks in the manufacturing line.

Secondly, robots are becoming more sensitive. The new applications for automation often require less heavy lifting and more delicate handling. Improvements in servo-motor quality and tuition gears, which make train doors slow down as they come together, allow a robot arm to swing fast and then pick up an object delicately.

Thirdly, automated factories increasingly have fully networked robots, sensors and quality controllers. This combination of automation with computing allows automated factories to learn from their mistakes and to optimise quality and flexibility.

We concluded that we should focus on the manufacturers of key components for more advanced automation and to avoid the well established heavy materials robot-makers of old. The dominant global manufacturers of servo motors are Japanese and so are the dominant makers of reduction gears. The robots that can take on the new factory tasks tend to need the more precise servo motors, gears, sensors and a higher number of arm articulations. There are thus opportunities to focus investments on the value-added elements of the automation wave and avoid the more deflationary products. These new investments have not only improved the balance of portfolios, but they also trade on reasonable valuations.

A focus on valuation

We have discussed permanent loss of capital, but should also discuss fairly-permanent loss of capital. The most common way equity investors lose money is by buying fashionable companies at high valuations. Companies become fashionable through their shares having performed well over recent years, so herd followers end up with portfolios of large positions in recent years’ outperformers at just the moment when those companies’ valuations are at a peak.

Many investors seem to believe they can manage equity risk by buying high-risk active funds alongside low-cost index funds. It should be mentioned, however, that there is evidence that most active managers outperform the index in bear markets, when investors most value this aspect.

Our process encourages us to take profits slowly in parts of our portfolio which become fashionable and reinvest in out-of-favour sectors on modest valuations. This generally leads to a better balanced portfolio, which we believe will be required to deliver persistent real returns through the changing economic conditions ahead.

Simon Edelsten is manager of the Artemis Global Select Fund

Charity Finance wishes to thank Artemis for its support with this article